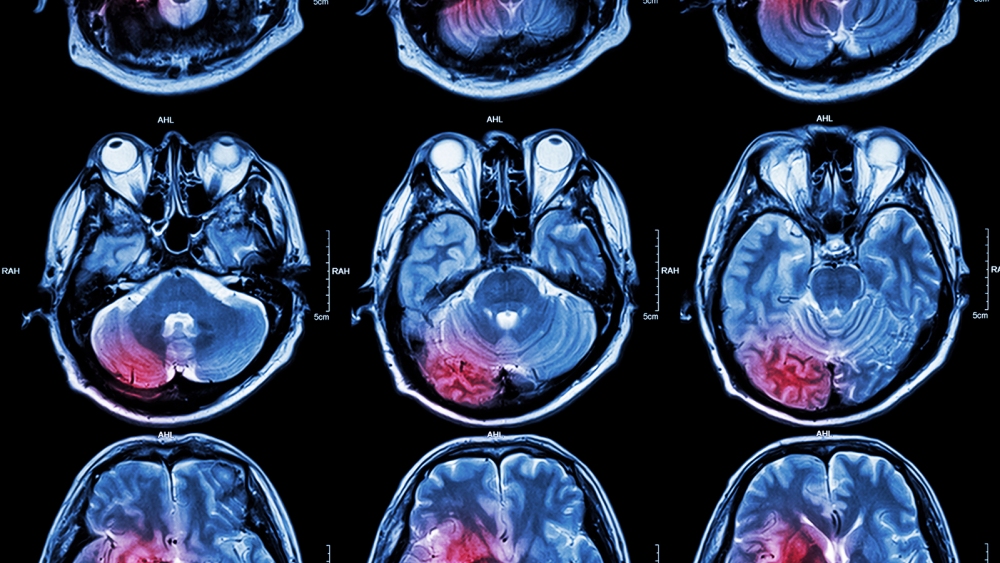

Genes from over 5,000 stroke patients hint at surprising treatment

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis researchers believe they have reopened the debate on a potential stroke treatment decades after it was abandoned.

Analyzing over 5,000 genomes from ischemic stroke patients, the team found two genetic markers that were associated with patient outcomes in the 24 hours after a stroke. Both genes were related to how a neurotransmitter called glutamate (yes, as in MSG) works in the brain.

The presence of too much glutamate can “excite” cells to death, a condition called “excitotoxicity,” which was thought to impact stroke patients until several failed clinical trials decades ago caused scientists to move on from the idea.

The WashU team believes their work warrants reevaluating glutamate — and stopping excitotoxicity — as a potential treatment.

The team found two genetic markers associated with outcomes 24 hours after a stroke. Both genes were related to how a neurotransmitter called glutamate (yes, as in MSG) works in the brain.

“There’s been this lingering question about whether excitotoxicity really matters for stroke recovery in people,” department of neurology head and co-senior author Jin-Moo Lee said in a statement.

Blocking excitotoxicity can cure strokes in mice, but every human trial of glutamate inhibitors in humans failed — “we couldn’t move the needle,” Lee said. But two genes out of the legion analyzed suggests there may be something to the treatment of excitotoxicity and stroke recovery after all.

“That’s pretty remarkable,” Lee said. “This is the first genetic evidence that shows excitotoxicity matters in people and not just in mice.”

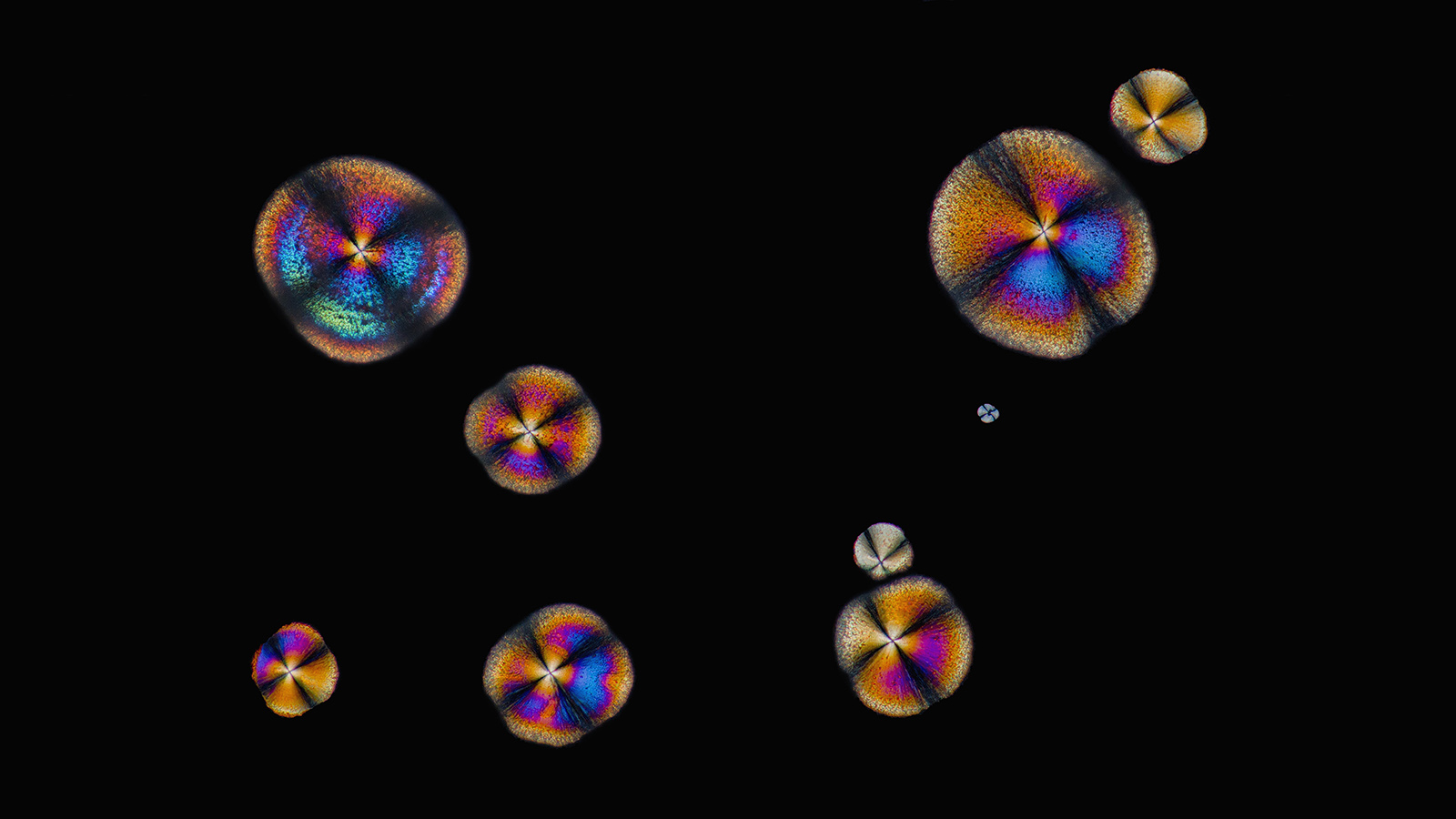

What is glutamate? The chemical is most famous — or infamous, depending on your dietary dogma — as an ingredient in the food additive MSG. While undoubtedly delicious, this “is not the reason for the enormous scientific interest in glutamate,” University of Oslo researchers explained in a Journal of Neural Transmission review on excitotoxicity.

Instead, glutamate is interesting because it’s the most common free amino acid — one not bound to a protein — in the brain. So scientists were surprised to discover that glutamate has the ability to increase the chances of neurons firing, which is known as an “excitatory effect.”

When that effect goes into overdrive, the cells can die.

The presence of too much glutamate can “excite” cells to death, a condition called “excitotoxicity.”

Excitotoxicity and stroke: In the 1990s, then Washington University neurology head Dennis Choi pioneered the connection between excitotoxicity and stroke.

His lab was among those able to to prove that strokes can cause neurons to release massive amounts of glutamate, but treating this glutamate glut to cure stroke never succeeded outside of mice, eventually causing the technique to be abandoned.

Lee, who worked with Choi, stayed interested, however. Recently, Lee and colleagues studied the genomes of 5,876 ischemic stroke patients across Europe, Asia, and North America.

Using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale, they characterized each patient’s recovery in the first 24 hours, then began scanning the genomes for any genes that were correlated with recovery.

“We started with no hypotheses about the mechanism of neuronal injury,” genetics researcher and co-senior author Carlos Cruchaga said. “We started with the assumption that some genetic variants are associated with stroke recovery, but which ones they are, we did not guess.”

Two genes stood out from the rest. One, called ADAM32, makes it easier for brain signals to pass from one neuron to another. The other, GluR1, is a glutamate receptor.

The researchers believe their work warrants reevaluating glutamate — and stopping excitotoxicity — as a potential stroke treatment.

In the years since anti-excitotoxicity drugs were abandoned, drugs that break up blood clots have become the standard therapy for ischemic stroke. These drugs help restore blood flow to the brain — which not only prevents more damage, but also means that medications for aiding recovery now may have a better chance of getting to the brain and working.

“We’ve learned a lot about stroke in the last few decades,” Lee said. “I think it’s time for a re-examination.”

This article was originally published on our sister site, Freethink.