Synthetic cartilage is now stronger than the real stuff

- Cartilage is a tough and malleable tissue found, among other places, in your nose, trachea, and joints.

- When cartilage in your joints wears out, the pain can be debilitating. Once worn down, cartilage does not repair itself very well, due to a lack of blood vessels. Replacement might be the only option.

- Researchers hope to use a new synthetic cartilage, tougher than the real thing, to prevent further degradation of the knee joint and the need for total knee replacement surgery.

Duke University researchers have created a synthetic cartilage that is stronger and more resilient than the real thing — the first artificial gel to pull that off, according to the researchers.

The material, called Ormi-CFC, could be the basis for next-gen implants that could relieve the pain and mobility issues for knee pain sufferers, including the over 32 million adults in the US suffering from osteoarthritis — the most common reason for knee replacement surgery, per the Mayo Clinic.

While a tried and true method for alleviating pain, knee replacement comes with all the risks inherent to surgeries, such as infection, and it necessitates physical rehab — all for implants that will eventually need to be replaced again.

But an implant that is stronger than natural cartilage could provide a long-lasting alternative.

Ormi-CFC’s aim “is to delay the need for knee replacement,” Benjamin Wiley, a chemistry professor at Duke who co-led the team with Duke mechanical engineering and materials science professor Ken Gall, tells Freethink. “By replacing damaged cartilage and inflamed bone, we hope to delay the further degradation of the joint.”

It could be a “dramatic change” in treatment for people at this stage of osteoarthritis, Wiley said in a statement.

Duke University researchers have created a synthetic cartilage hydrogel that is stronger and more resilient than the real thing.

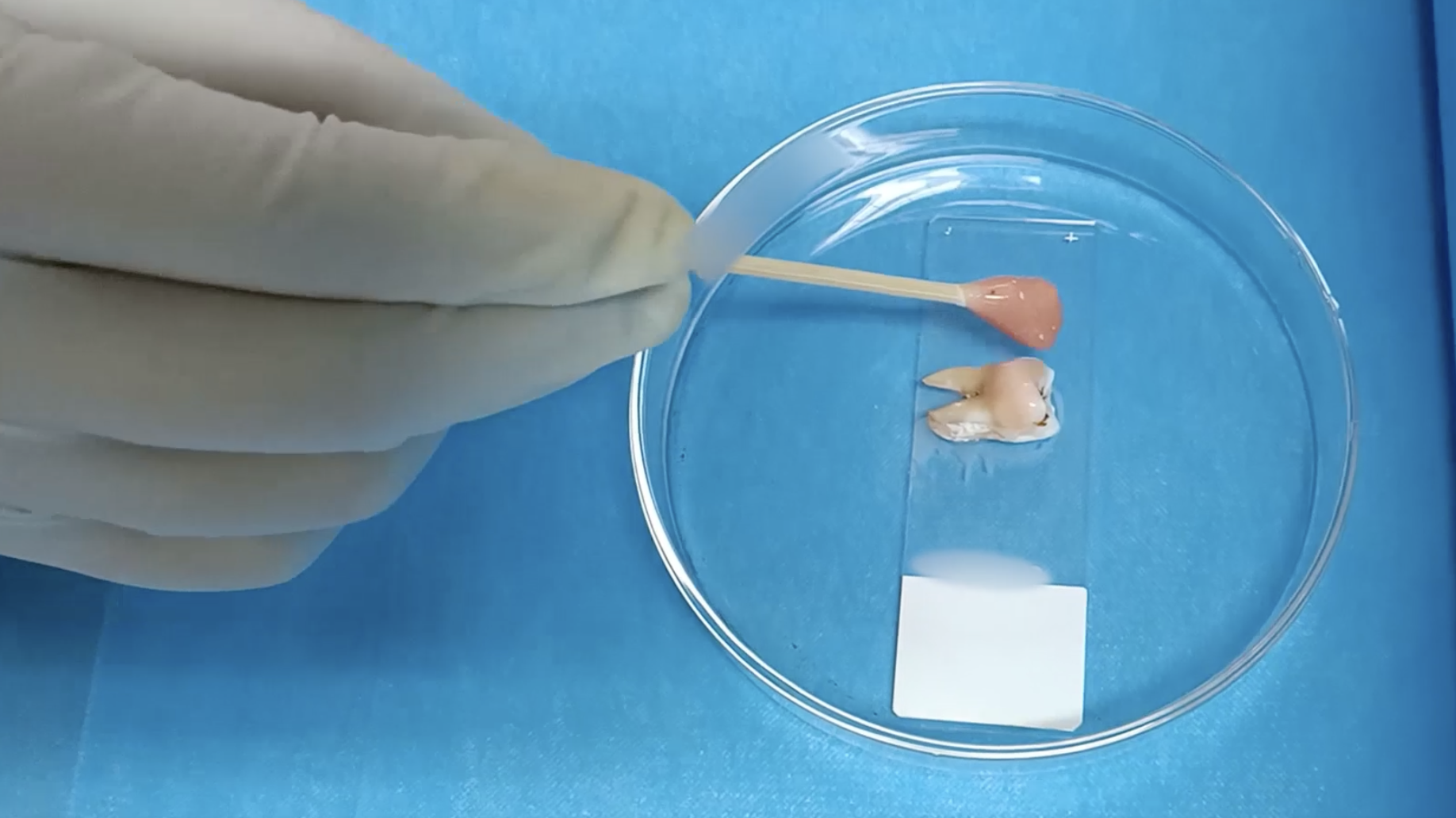

The first implants using the synthetic cartilage are being developed and tested in sheep now by Sparta Biomedical; both Wiley and Gall have an equity interest in the company.

“This implant is intended for individuals with knee pain, but for whom the damaged area is not so extensive [as] to need a total knee replacement,” Wiley tells Freethink.

“There is currently no good solution for this group of people.”

Cartilage challenges: Cartilage is a tough and malleable tissue found, among other places, in your nose, trachea, and, of course, joints.

When cartilage in your joints wears out, the pain can be debilitating.

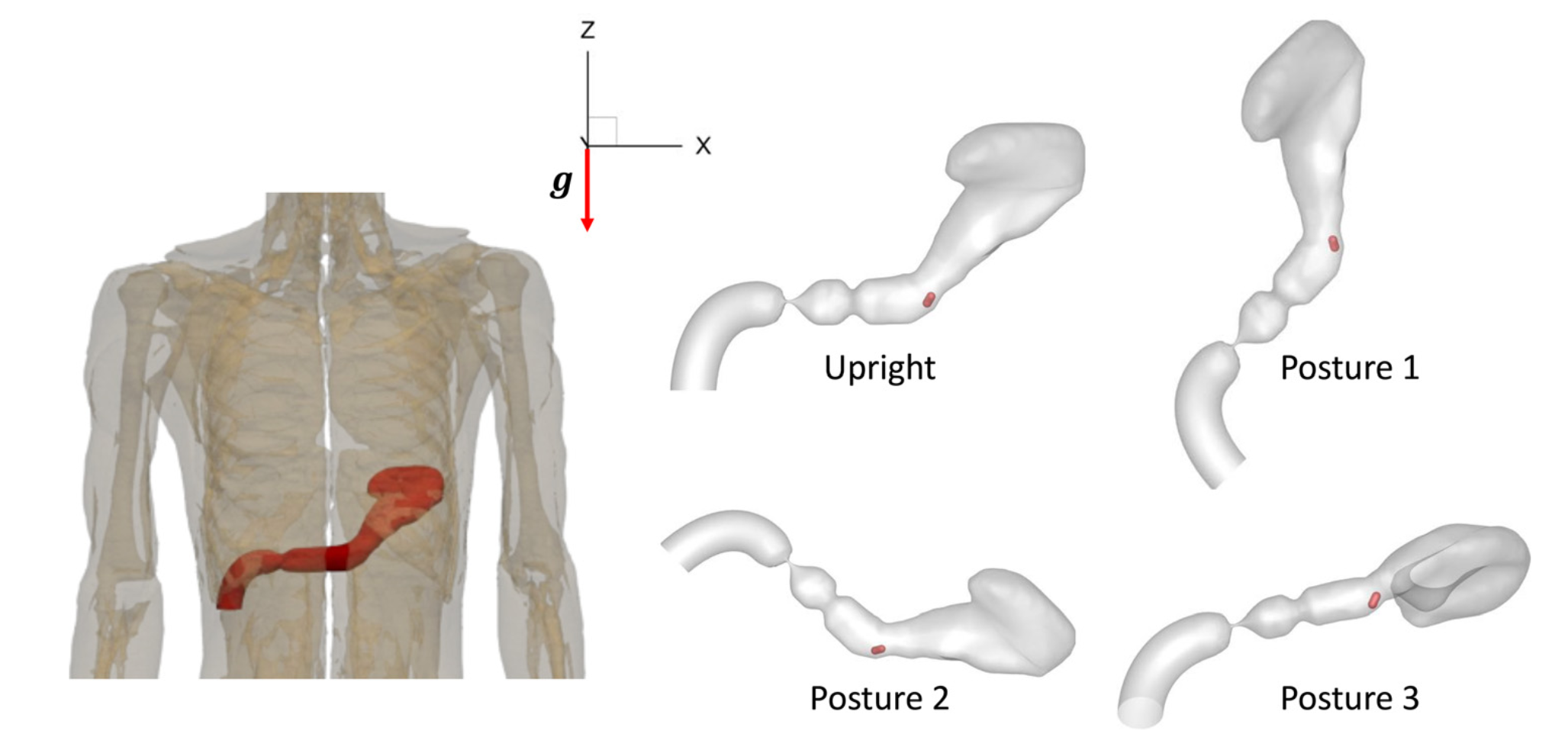

Inside your joints, cartilage performs three critical functions: It cushions the bones, acting like a shock absorber; it lubricates the joints and lessens friction, allowing the bones to smoothly move across each other; and it helps provide structural support for the joints when moving and as an anchor point, connecting tendon, muscle, and ligament to bone.

In osteoarthritis, that crucial cartilage breaks down, with a number of deleterious results, including pain, limits on activities and work, social isolation, and depression.

Once worn down, cartilage does not repair itself very well, due to a lack of blood vessels, Wiley said.

When this happens inside your knees, a knee replacement can become the only effective solution.

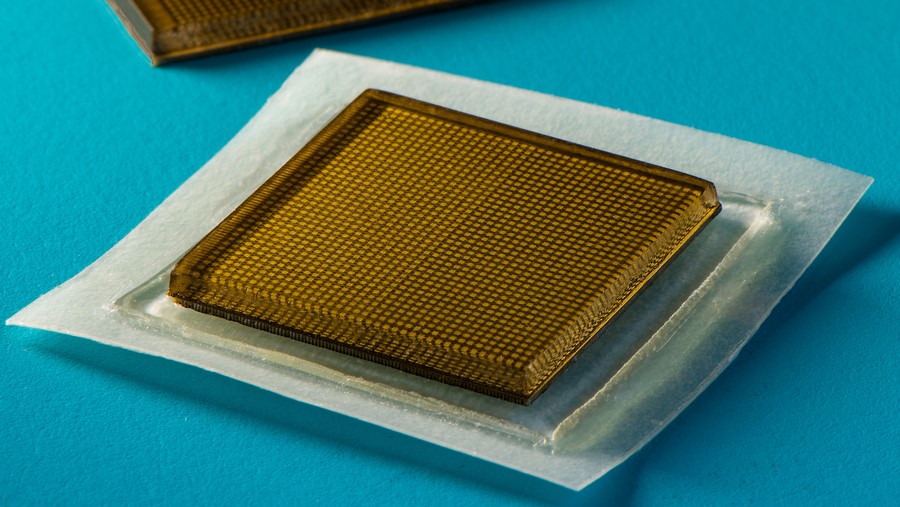

Outperforming nature: The Duke team’s synthetic cartilage, published in Advanced Functional Materials, was made from thin sheets of cellulose fibers — the stuff in wood, leaves, or other plant material. The fibers were laced with a goo called “polyvinyl alcohol” to create a hydrogel.

Those fibers are simulating the collagen fibers in your cartilage, Wiley said, while the goo helps it go back to its original shape.

“It’s really off the charts in terms of hydrogel strength.”

BENJAMIN WILEY

Natural cartilage can withstand 5,800 and 8,500 pounds per inch of “tugging and squishing,” as Duke puts it, respectively. The team’s new gel is 26% stronger than the real deal when tugged, and 66% stronger when squished.

“It’s really off the charts in terms of hydrogel strength,” Wiley said. Creating a better cartilage replacement meant surmounting two difficult engineering challenges.

Build a better body: Most hydrogels are toughened up by repeatedly freezing and thawing the gel, forming crystals inside of it that push water out and help the polymer chains hold together better.

But the Duke team took the exact opposite approach.

Rather than freezing their synthetic cartilage, the researchers heated it, cranking up the temperature before letting it cool back down slowly, a process called annealing. The annealed gel creates even more crystals, allowing it to handle five times as much pulling stress and almost twice the squeezing stress as freeze-thawed gels.

Even if you make a superstrong gel, however, there’s another big challenge to creating knee implants: getting the stuff to stick properly.

Clinical trials of implants using the hydrogel are expected to begin in the spring of 2023.

According to Duke, previous studies have found that hydrogel implants have a tendency to slip or break loose when attached right to bone. Instead, the team’s hydrogel can be clamped to a titanium base that’s anchored to a hole.

Stress testing the gel by rubbing it against natural cartilage at a pressure similar to that exerted on the knee while walking showed that the synthetic cartilage was actually three times more wear resistant than natural cartilage, New Atlas reported.

Next steps: Before it can be implanted into patients, the synthetic cartilage will need to be clinically tested in people to ensure first that it is safe and effective. Eventually, the hydrogel may be able to be used in total knee implants as well, but it will need to prove itself in smaller applications first, Wiley tells Freethink.

Clinical trials could start as soon as April 2023.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.