Is “The Great Gatsby” really that great of a book?

- The beloved novel was panned by critics upon publication.

- These critics complained about its forced writing style and underdeveloped characters.

- Even if The Great Gatsby isn’t all that great, it’s a fitting portrayal of the Roaring Twenties.

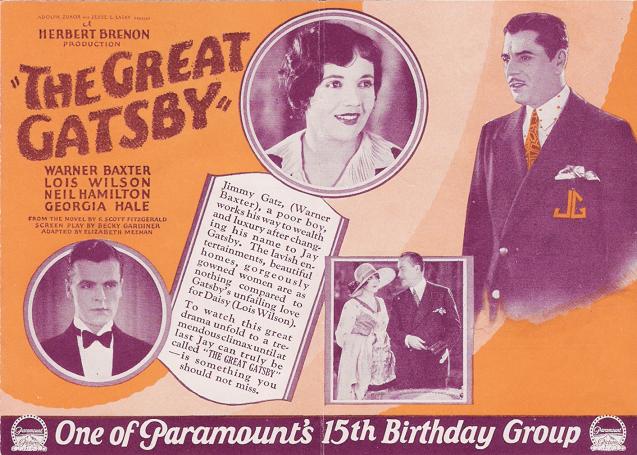

It’s been nearly a century since F. Scott Fitzgerald sent his manuscript for The Great Gatsby to the printing press. During that time, opinion on what has inarguably become the author’s best-known work has shifted quite a bit. Many refer to it as “The Great American Novel.” Many others insist it is not a novel but a novella, and not a particularly great one at that.

Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson famously said he typed out the entirety of The Great Gatsby to teach his fingers what it felt like to produce impeccable writing. His impression of the book could not have been more different from that of its earliest reviewers, who called Fitzgerald “bored and tired and cynical,” and his writing style, always striving for elegance, “painfully forced.”

All this polarization raises many interesting questions. Why has the book proven so divisive? Do the critics make a valid point, or should we dismiss them the way that a jealous Virginia Woolf sought to dismiss James Joyce’s Ulysses? Did Fitzgerald’s short-term failure grant him immortality in the long run? And, finally, is The Great Gatsby really as great as our high school teachers told us it was?

The Great Gatsby falls flat

Although The Great Gatsby received largely negative reviews upon its release in 1925, it did have its fans. Lillian Ford from the Los Angeles Times wrote it was “a work of art,” while New York Times journalist Edwin Clark called the book, curious, mystical, and glamorous, writing that it “takes a deeper cut at life than hitherto has been enjoyed by Mr. Fitzgerald.”

Unfortunately for Fitzgerald, their mild praise was drowned out by the frustration of other more authoritative critics. “When This Side of Paradise was published,” Harvey Eagleton wrote in The Dallas Morning News, referring to another book from the author, “Mr. Fitzgerald was hailed as a young man of promise, which he certainly appeared to be. But the promise, like so many, seems likely to go unfulfilled.”

The Canadian-American journalist Isabel Paterson didn’t think that The Great Gatsby was as bad as other people were saying it was, but she didn’t think it was exceptionally good either. In her review for The New York Herald, she concluded it was “a book for the season only,” adding that, “what has never been alive cannot very well go on living.”

Even some of Fitzgerald’s friends were disappointed with the book. “To make Gatsby really Great,” Edith Wharton, a fellow author, wrote to him in April of 1925, “you ought to have given us his early career (not from the cradle—but from his visit to the yacht, if not before) instead of a short resume of it. That would have situated him & made his final tragedy a tragedy instead of a fait divers for the morning papers.”

A glorified anecdote?

It is worth taking a closer look at one of these negative reviews to better understand why The Great Gatsby rubbed so many of its first readers the wrong way. In a review published in The Chicago Sunday Tribune on May 3, 1925, journalist H.L. Mencken goes to considerable lengths to prove to his readers why Fitzgerald’s latest work should not be mistaken for Literature with a capital L.

Echoing Paterson’s statement that “what has never been alive cannot very well go on living,” Mencken complains that Fitzgerald focuses too much on narrative structure and not enough on characterization — one of the things that distinguishes a great novel from an interesting story. The Great Gatsby, in other words, is well-told but not impactful. It is, as Mencken says, “in form no more than a glorified anecdote.” He continues:

What ails it, fundamentally, is the plain fact that it is simply a story—that Fitzgerald seems to be far more interested in maintaining its suspense than in getting under the skins of its people. It is not that they are false: it is that they are taken too much for granted. Only Gatsby himself genuinely lives and breathes. The rest are mere marionettes—often astonishingly lifelike, but nevertheless not quite alive.

Fitzgerald reinstated

While The Great Gatsby is more beloved today than it was in Fitzgerald’s own time, occasional criticisms — presented as “hot takes” — continue to appear in magazines. When Baz Lurhmann’s mediocre film adaptation released in 2013, for example, Joshua Rothman from The New Yorker said it was “trashy, tasteless, seductive, sentimental, aloof, and artificial,” just like its source material.

But Rothman’s critique is more nuanced than that of his predecessors. Using the film’s release to discuss the reasons for the book’s latent success, he makes two interesting arguments: first, that it’s popular with present-day readers because it embraces the extravagance of the Roaring Twenties; and, second, that it was unpopular with contemporary readers because this embrace borders on parody and criticism.

“It’s popular because we still live in that atmosphere today,” he explains. “Fitzgerald’s novel is cool, sexy, stylized, and abstract; there’s a dreamlike falseness, a hollowness, an unreality to it, and that apparent superficiality is part of what makes it fascinating. It’s modernist and European without being arty […] for all its strangeness, it also possesses a glamorous, crowd-pleasing commercialism.”

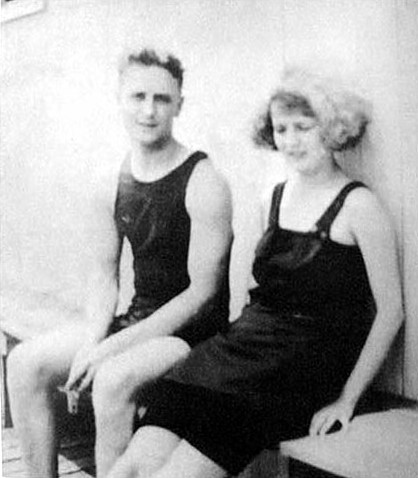

To us, the setting of The Great Gatsby comes across as an exaggerated fantasy. For Mencken and Paterson, it was a stylized but ultimately faithful depiction of a reality they knew all too well. As did Fitzgerald himself. Like Daisy and Tom Buchanan, he and his wife Zelda lived a life confined to fancy hotel rooms, invite-only parties, and the backseats of luxury cars going way over the speed limit.

It was a lifestyle that eventually destroyed Fitzgerald, who died of complications of alcoholism at 44. While The Great Gatsby was written during the peak of his life and career, the book’s underlying melancholy — encapsulated in Daisy hoping her daughter will be “a beautiful little fool” — hints that the author was, on some level, aware of where he would end up. If The Great Gatsby isn’t great, it’s certainly poetic.