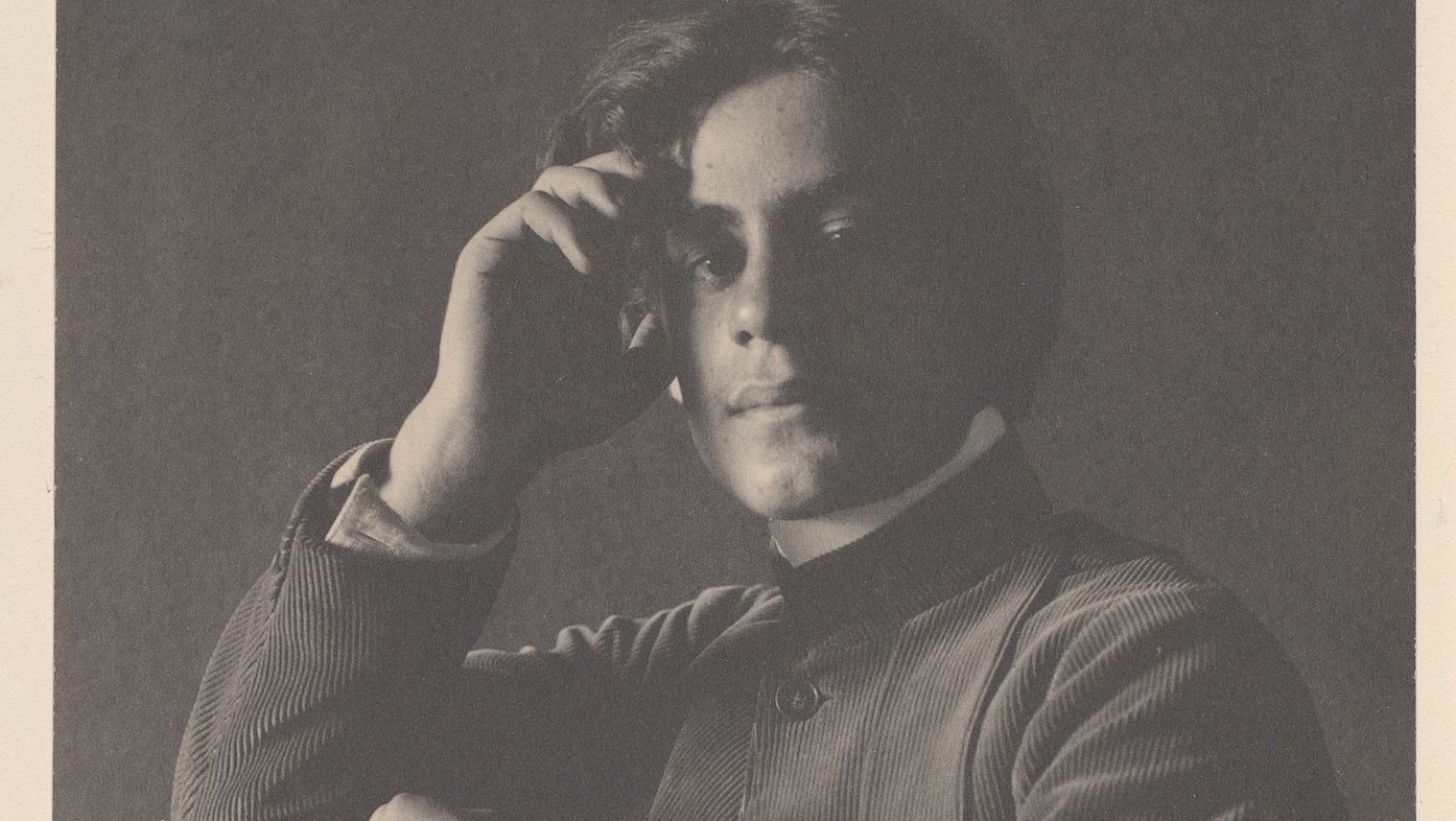

Joy Harjo named first Native American poet laureate

J. Vespa / Contributor

- Joy Harjo is a poet, author and musician, and is an active member of the Muscogee Nation.

- Poet laureates are charged with overseeing poetry readings at the Library of Congress, and with promoting poetry to the nation.

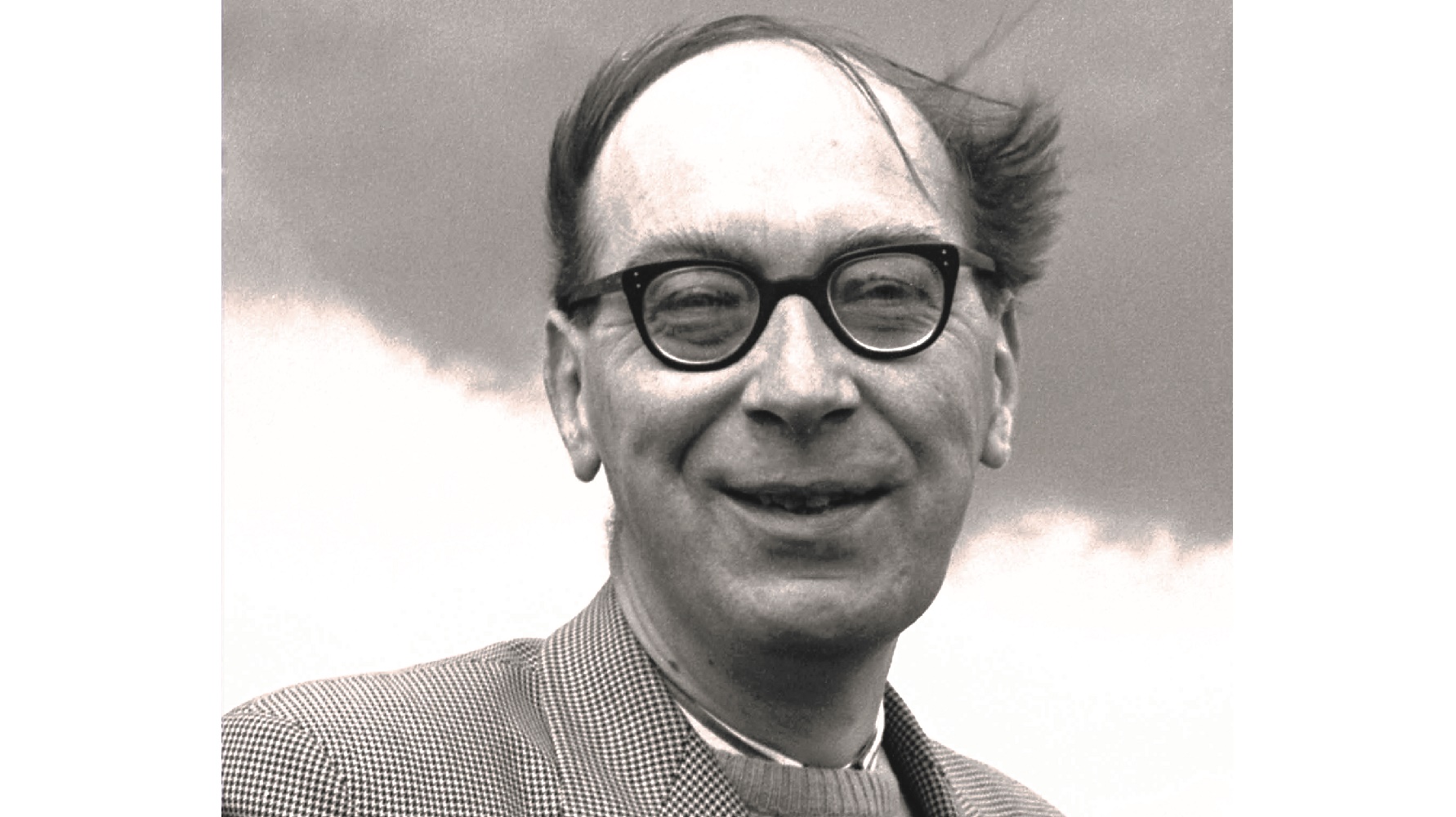

- Harjo succeeds poet and educator Tracy K. Smith.

The Library of Congress has named Joy Hargo as the United States’ 23rd Poet Laureate for 2019-2020. Harjo – a poet, author, musician and member of the Muscogee Nation – is the first Native American to hold the title.

“Joy Harjo has championed the art of poetry—’soul talk’ as she calls it—for over four decades,” Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden said in a release. “To her, poems are ‘carriers of dreams, knowledge and wisdom,’ and through them she tells an American story of tradition and loss, reckoning and myth-making.”

Harjo, 68, began writing as a college student, during “the beginning of a multicultural literary movement” that made her realize poetry was available to everyone, she told The New York Times. “It became a way to speak about especially Native women’s experiences at a time of great social change.”

Since, she’s written more than eight books of poetry, a memoir and two childrens’ books.

“What a tremendous honor it is to be named the U.S. poet laureate,” Harjo said in a Library of Congress press release. “I share this honor with ancestors and teachers who inspired in me a love of poetry, who taught that words are powerful and can make change when understanding appears impossible, and how time and timelessness can live together within a poem. I count among these ancestors and teachers my Muscogee Creek people, the librarians who opened so many doors for all of us and the original poets of the indigenous tribal nations of these lands, who were joined by diverse peoples from nations all over the world to make this country and this country’s poetry.”

Harjo’s poems often touch on nature, womanhood, definitions of self, fear, grief, generations, spirituality and Native American culture.

“My poems are about confronting the kind of society that would diminish Native people, disappear us from the story of this country,” she told the Times.

In poetry performances, Harjo is known for singing and inflecting her voice, giving her a uniquely musical style. Outside of poetry, Harjo has toured with the bands Poetic Justice and Arrow Dynamics, and she’s released five albums of original and award-winning music, on which she sings and plays the saxophone.

Harjo told the Times she’s “still in a little bit of shock,” and doesn’t yet know what she’ll focus on during her time as poet laureate – appointees are asked to oversee poetry readings at the Library of Congress and promote the art to the country.

Harjo said poetry has the power to connect people together.

“Just as when I started writing poetry, we’re at a very crucial time in American history and in planetary history,” Harjo told the Times. “Poetry is a way to bridge, to make bridges from one country to another, one person to another, one time to another.”

Here’s one of her poems, entitled “Grace”.

I think of Wind and her wild ways the year we had nothing to lose and lost it anyway in the cursed country of the fox. We still talk about that winter, how the cold froze imaginary buffalo on the stuffed horizon of snowbanks. The haunting voices of the starved and mutilated broke fences, crashed our thermostat dreams, and we couldn’t stand it one more time. So once again we lost a winter in stubborn memory, walked through cheap apartment walls, skated through fields of ghosts into a town that never wanted us, in the epic search for grace.

Like Coyote, like Rabbit, we could not contain our terror and clowned our way through a season of false midnights. We had to swallow that town with laughter, so it would go down easy as honey. And one morning as the sun struggled to break ice, and our dreams had found us with coffee and pancakes in a truck stop along Highway 80, we found grace.

I could say grace was a woman with time on her hands, or a white buffalo escaped from memory. But in that dingy light it was a promise of balance. We once again understood the talk of animals, and spring was lean and hungry with the hope of children and corn.

I would like to say, with grace, we picked ourselves up and walked into the spring thaw. We didn’t; the next season was worse. You went home to Leech Lake to work with the tribe and I went south. And, Wind, I am still crazy. I know there is something larger than the memory of a dispossessed people. We have seen it.