Optical illusion: Why Hans Holbein hid a creepy skull in “The Ambassadors”

- Holbein’s The Ambassadors would seem like an ordinary 16th century portrait were it not for an indiscernible shape appearing in the foreground.

- When looked at from a different angle at the bottom-right corner of the painting, this shape is revealed to be a skull — a visualization of the saying “memento mori.”

- But while being mindful of death helps you make better choices in life, it also makes you lose sight of the world around you; you cannot see both images at the same time.

At first glance, The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger appears to be a fairly straightforward 16th century portrait. Two noteworthy Europeans — French diplomats based in London — were made to look their very best. Standing tall and proud in peacock-like ceremonial garb, they surround themselves with prized possessions indicating their standing: Persian rugs and miniature globes suggest they are well-traveled individuals, while musical instruments and sundials hint at an interest in art and science.

According to the standards of the genre Holbein worked with and our expectations of the time in which he lived, nothing about his picture seems to be particularly out of the ordinary. That is, until you take a closer look at the foreground, where you will find — imposed in front and on top of our ambassadors and their belongings — a strange, elongated object. Drawn from an entirely different perspective than the rest of the painting, it is all but indiscernible to the viewer and almost looks as if it came crashing into the composition from another dimension.

The Ambassadors can be viewed inside the National Gallery in London, and the room in which it has been put on display is unlike any other. Instead of admiring the painting head-on, most visitors can be found crowding around its bottom-right corner. From this distorted perspective, the ambassadors are no longer discernible, but the shape in the foreground is now clearly visible and representational. The object, it turns out, is a human skull, lying idly against the leg of the table, right in between the two ambassadors.

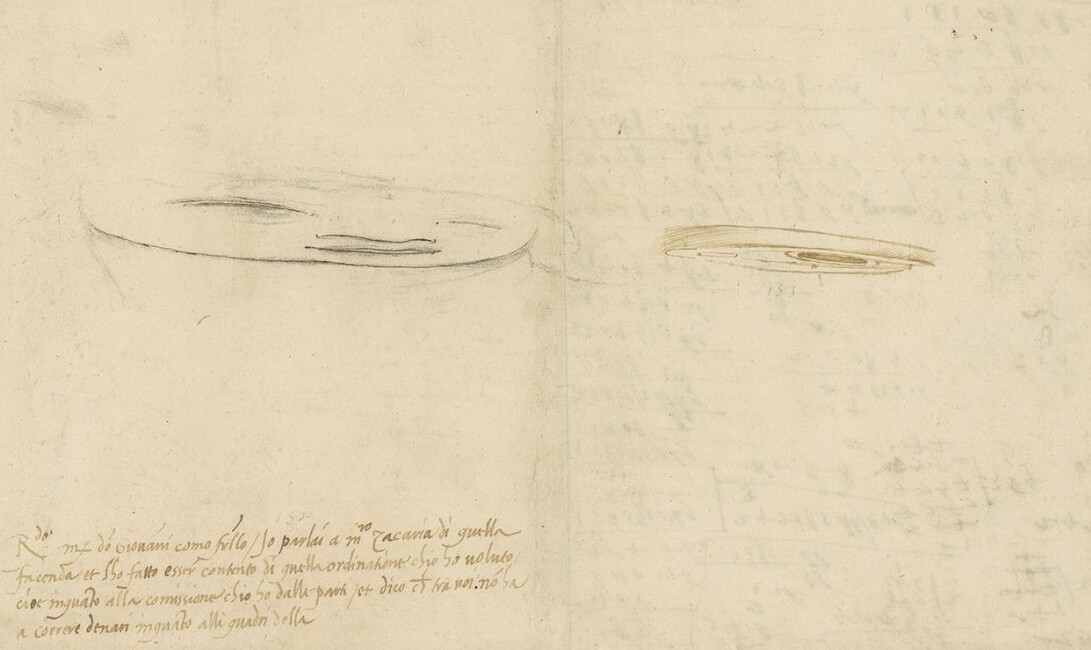

Art historians refer to this technique as anamorphosis, or distorted projection, and it was popular during the Renaissance. The first artist who tried to work an understanding of optics into his art was Leonardo da Vinci, whose Codex Atlanticus — a collection of sketches, blueprints and essays — includes two familiarly elongated drawings which, when viewed from a specific perspective, resemble a face and eye. The resulting images were enticing combinations of artistic skill and scientific knowledge, inspiring subsequent generations of painters.

In the 17th century, scientists like Salomon de Caus and Jean François Niceron drew up a mathematically constructed grid system that showed artists how to paint or draw anything from an anamorphic perspective. This proved particularly useful for churches and cathedrals. In 1690, Church of St. Ignazio commissioned Andrea Pozzo to create a painting that, when looked at from below, would make the flat ceiling appear as though it was domed or vaulted. Nowadays, the tradition is being carried on by street artists.

Hans Holbein and “memento mori”

But back to The Ambassadors. In Hans Holbein’s case, what interested him about anamorphism was not the technique’s underlying scientific principles but the meaning it acquired when used in this way on this particular painting. While the painter’s life was wedged in between the end of the Renaissance and the beginning of the Scientific Revolution, religious beliefs from both the Protestant and Catholic variety still held considerable sway over the Germanic art institutions of which Holbein was a part.

One of these beliefs was the infamous saying “memento mori,” Latin for “remember that you die.” Though its origins date back to Greek antiquity, the saying developed alongside the Christian faith whose teachings it summarized. Monks and Bible scholars popularized the phrase under the belief that being conscious of your own impending doom would make you behave like a better person. Since status, money, and power cannot follow you into the grave, the pursuits that lead to the fulfillment of these earthly desires ought to be ignored.

The skull in The Ambassadors is a visualization of the “memento mori” saying. Hans Holbein had managed to paint death as it appeared in life: obscured yet omnipresent. Just as death can ambush us on the moments we least expect it, so too do we not see the skull in the painting despite the fact that it is hiding in plain sight. Only once we become informed of its presence do we begin to adjust our vision and reevaluate what we had previously seen. In the process, the painting has acquired an entirely different meaning.

First and foremost, the presence of the skull recontextualizes our thoughts about the ambassadors and their refined paraphernalia. Already two new interpretations of the image arise. On one hand, the ambassadors — dressed in their peacock-like ceremonial garb posing next to their possessions — are made to look rather unsympathetic, as if their minds are set on wealth and influence rather than what is truly important. On the other, one could argue that some of these pursuits, like their devotion to the arts and sciences, is actually driving death — and their fear of it — away.

Considering that “memento mori” was the personal motto of one of Holbein’s sitters, the second interpretation seems more appropriate. Rather than forgetting about their own mortality, the ambassadors remain conscious of death’s inevitability. The realization humbles them and leads them to reassess their priorities. At the same time, the concept of death is reduced from a looming threat to what looks like a stain on the window or — in the eyes of modern audiences — a smudge on the lens.

The skull, and the way in which Hans Holbein painted it, says a lot about our relationship with death. While both the ambassadors and the skull can be viewed from different angles, it is impossible to look at both images at the same time. Conceptually, this means that, while being mindful of death can be helpful, it also makes us forget about life as it unfolds around us. Whether Holbein meant to add his own critical spin on “memento mori” is unclear. Still, it is a testament to the many ways in which you can look at this amazing painting.