A brief overview of the history of European portraiture

- The way that artists chose to portray their contemporaries can tell us a lot about the times in which they lived and the values their societies maintained.

- Where portrait painting from ancient Greece and Rome was naturalistic like their sculptures, the Middle Ages saw a shift toward religious iconography.

- Realism made a comeback during the Renaissance, but by that time, the genre had acquired a variety of new social and cultural purposes.

Before the invention of photography, portrait painting was the only way through which people could capture and record the likeness of their fellow man. Over time, portraiture became known as one of — if not the most — intimate of genres, establishing a connection between painter and subject. They also serve as snapshots of their time, allowing modern viewers to better understand not just the principles of past artistic movements but also what the sitter – and the society they lived in – considered beautiful, noble, and important.

Antiquity and the funeral paintings of Faiyum

Portrait painting is almost as old as painting itself and can be traced back to archaeological finds from the Fertile Crescent. Paintings uncovered from the ruins of ancient Egypt show that the world’s first portrait painters did not strive for accuracy but instead rendered their subjects in a highly stylized manner. Rulers were the only individuals considered worthy of being immortalized on canvas. They were either depicted as themselves or as the reincarnations of gods, and they were always drawn in profile.

Most people remember ancient Greece for their lifelike marble statues, but the Greeks were prolific painters as well. According to the Roman historian Pliny the Elder, portraiture in Greek society was widely established and practiced by both male and female artists. Unfortunately, all portrait paintings produced during this period have been lost to time — not because they were destroyed by military conflicts or natural disasters, but because the materials used were impermanent.

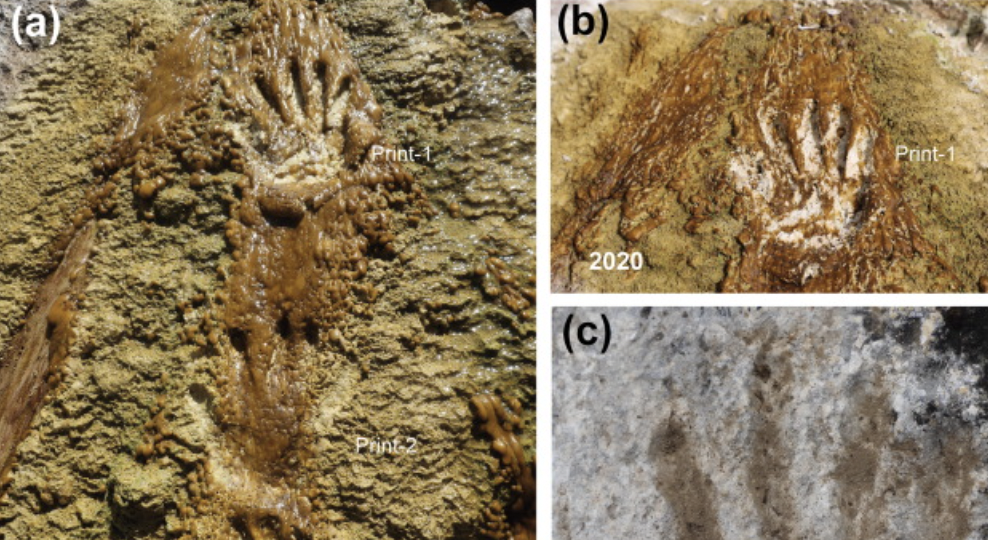

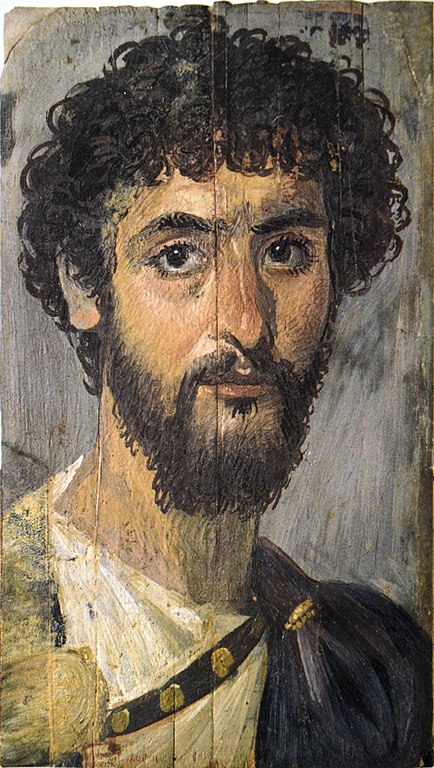

Like the Greeks who had inspired them, Roman artists placed great emphasis on capturing the likeness of their sitter. Renaissance explorers were fortunate enough to unearth a collection of gorgeous yet haunting funeral portraits from the Roman province of Faiyum in Egypt. These naturalistic portraits, the sole survivors of their artistic tradition, were painted on wooden boards and used to cover the faces of upper class citizens during their burial ceremonies.

The discoveries at Faiyum give art historians an impression of what naturalistic portraits looked like before the Renaissance, a period which continues to define the genre to this day. The funeral portraits are a clash between Roman, Greek, and Egyptian styles. Broad brush strokes combined with bold colors give the portraits an impressionistic effect. At the same time, their frontal perspective and accentuated facial features serve as precursors to Byzantine icon painting.

The Middle Ages and Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait

The Middle Ages, ushered in by the fall of the Roman Empire and the dissolution of its cultural influences in central and northern Europe, saw a complete overhaul in the style of portrait painting. If art from antiquity was inspired by the writings of important thinkers such as Plato and Socrates, European portraits from the Middle Ages were based on teachings from the Bible. Until the Reformation, paintings could be found only in churches and parishes.

For a long time, portraiture no longer existed as its own genre. Paintings either depicted deceased saints or characters from the Bible, which were drawn from description and imagination rather than references. If a regular person was featured in a painting, they were depicted as partaking in a recognizable religious scene such as the birth or death of Christ. These paintings were called donor portraits, and their purpose was to inspire the commissioner and their loved ones toward prayer.

Though portraiture briefly disappeared, the genre was resurrected and revolutionized by painters from Germany and the Netherlands. Early Netherlandish painters, bridging the gap between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, introduced a number of features we take for granted today. Jan van Eyck’s infamous Arnolfini Portrait (1434) emphasizes not only the faces of their sitters but their possessions as well: The ceremonial garb, wooden slippers, and partially lit chandelier indicate the couple’s married status.

In portraiture, the smallest touches can hold the greatest significance. A case-in-point is Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait from 1500. Though the painting may strike us as unconventional today, its naturalism provided a stark contrast with the stylized icon paintings in vogue at the time. More remarkable still is Dürer’s position. Facing the viewer head-on, the painter depicted himself in a pose that — up until that point — had been reserved exclusively for Christ.

The Renaissance and onward

Rogues like Dürer and Van Eyck notwithstanding, portraiture did not make a large-scale comeback until the start of the Renaissance — a period during which the genre acquired new meanings and purposes. As early as 1336, the Italian poet Petrarch commissioned the Sienna-based painter Simone Martini to create a painting of his muse, countess Laura de Noves. Petrarch did not have any symbolic use of the painting; he simply wanted to commemorate the countess’ beauty.

This move from religious iconography toward individual representation continued on in the Netherlands, where a Golden Age of intercontinental trade led to the rise of a relatively wealthy middle class that used hired portrait painters to capture not just their likeness but their social standing as well. Especially popular became the sub-genre of group portraits. These paintings, like Rembrandt’s Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild, often depicted members of businesses surrounded by objects that hinted at their wealth and morals.

While representation of the middle class was considered the norm in Holland, other, more politically conservative European countries saw their painters stick with royalty and nobility. Hyacinthe Rigaud may have set the gold standard with his pompous rendition of “Sun King” Louis XIV, who is depicted at the height of his power. From the coronation mantle to the angle Rigaud used, every element of the painting works together to create a single, instantly recognizable effect: making the king appear larger than life.

Over the next few centuries, portraiture would receive numerous other noteworthy overhauls. However, the biggest changeup to the formula came not from the painters themselves but an entirely unrelated invention: the camera. Now that people were able to capture each other’s likenesses instantly and with greater precision than any human hand ever could, modern painters — much like the ancient ones — finally returned to abstraction.