Tolkien disliked Shakespeare, but the Bard still shaped Middle-earth

- Tolkien’s Middle-earth has many historical and literary influences.

- References to William Shakespeare’s plays are not always obvious, in part because Tolkien was no great fan of the Bard.

- Even so, Shakespeare influenced Tolkien’s Middle-earth in subtle, and not-so-subtle, ways.

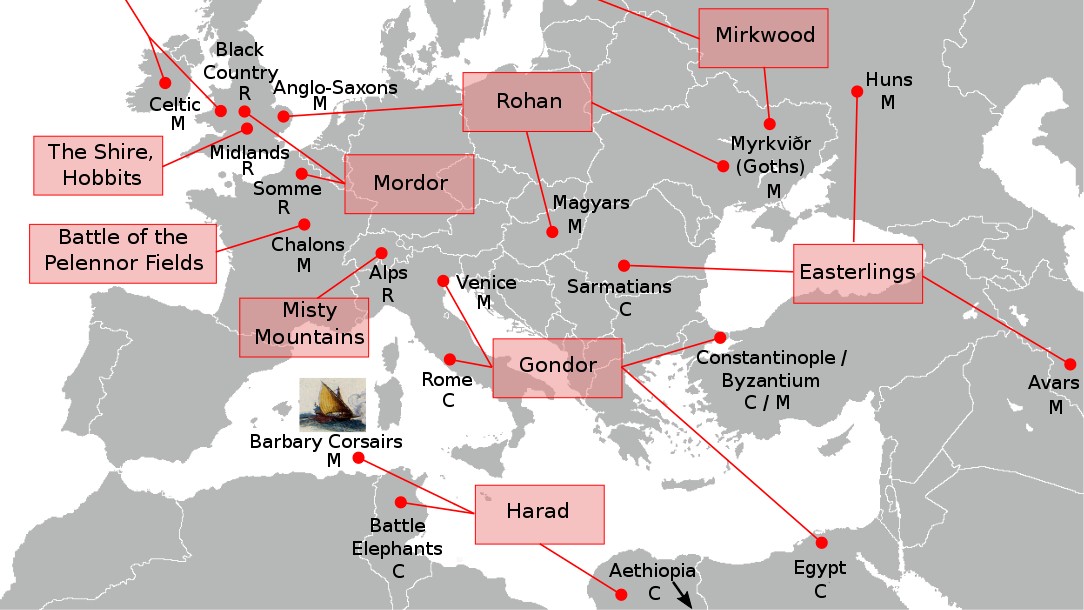

Contrary to popular opinion, J.R.R. Tolkien did not conjure Middle-earth from the depths of his imagination alone. When constructing his fictional universe, the celebrated fantasy writer took inspiration from a variety of literary and historical sources. These include the legend of Beowulf, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, the Anglo-Saxon invasion of England, and — last but not least — the plays of William Shakespeare.

The Bard’s influence on Middle-earth may not be obvious, not in the least because Tolkien didn’t really care for him. Tolkien’s scorn for Shakespeare — one he shared with literary heavyweight Leo Tolstoy — dates back to his school days. Serving as the secretary of the debating society at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, the future creator of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings once argued that Shakespeare’s plays were written by Francis Bacon, shocking his peers with what the student newspaper described as “a sudden flood of unqualified abuse upon Shakespeare, upon his filthy birthplace, his squalid surroundings, and his sordid character.”

Tolkien disliked Shakespeare so much that he once expressed regret at referring to one of Middle-earth’s races as Elves. While elves “is a word in ancestry and original meaning suitable enough,” he wrote to a friend in 1954, “the disastrous debasement of this word, in which Shakespeare played an unforgivable part, has really overloaded it with regrettable tones, which are too much to overcome.” Although he does not specify any plays, Tolkien must have had A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Merry Wives of Windsor in mind. Both present elves as whimsical, lighthearted creatures who live in enchanted woods — a far cry from noble beings inhabiting the dark and dangerous forests of Middle-earth.

But while Tolkien was no fan of Shakespeare, his animosity toward the Bard has most certainly been exaggerated and oversimplified. For evidence, look no further than a letter he wrote to his son Christopher after seeing a performance of Hamlet. In it, Tolkien seems to argue, as many have done before and since, that Shakespeare ought to be seen on stage rather than read. “The part that came out as the most moving,” he admits, “almost intolerably so, was the one that in reading I always found a bore: the scene of mad Ophelia singing her snatches.”

Echoes of Hamlet and other plays can be heard throughout Middle-earth. But whether those echoes are positive or negative, conscious or unconscious, are different questions altogether.

Beware the prophecy

Many potential references to Shakespeare are so small and incidental that they might not have been intended at all. For example, critics have compared A Midsummer Night’s Dream‘s Oberon to The Hobbit‘s Gandalf because both play the role of the benevolent yet powerful guardian. Also, Bilbo tricking the trolls into arguing among themselves is similar to how Puck starts an argument between Lysander and Demetrius. And Beorn shapeshifting into a bear sort of resembles Theseus and Hippolyta assuming different identities.

Other references hold up better under scrutiny. Tolkien’s Elven prophecy that the Witch-king of Angmar would not fall “by the hand of man” mirrors the famous prophecy from Macbeth: “Be bloody, bold, and resolute. Laugh to score / The power of man, for none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth.” This parallel is sustained throughout each narrative. In The Return of the King, the Witch-king is defeated by Éowyn, a princess of Rohan in disguise. In Shakespeare’s tragedy, Macbeth comes face to face with Macduff, whom he learns was brought into the world by way of C-section (“from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripp’d”) and is therefore capable of harming him.

The Éowyn subplot also appears to pay homage to King Lear. For example, the warning given to her by the Witch-king — “Come not between the Nazgûl and his prey” — is clearly reminiscent of Lear’s order to “Come not between the dragon and his wrath.”

The march of Birnam Wood

While the majority of Tolkien’s Shakespeare references amount to little more than window dressing, some contain deeper meanings. Tolkien fans who know their Shakespeare will be able to guess that Aragorn is the rightful heir of Gondor after reading the so-called “Riddle of Strider” by which his character is introduced. One of the riddle’s most iconic lines, “All that is gold does not glitter,” alludes to a verse from Henry IV Part I — “And like bright metal on a sullen ground / My reformation, glitt’ring o’er my fault.” The verse is about a prince who eschews his royal duties in favor of living as a vagrant, much like Aragorn did, and it is delivered by the titular Prince Henry himself.

At the same time, given Tolkien’s love of Chaucer, it’s entirely possible that the “Riddle of Strider” was partly or even entirely inspired by a more comparable excerpt from The Canterbury Tales: “But al thing which shineth as the gold, nis nat gold, as that I have heard it told.”

Ironically, the greatest influence Shakespeare had on The Lord of the Rings resulted from Tolkien wanting to rewrite a plot line he felt Shakespeare mishandled. In addition to the poorly worded prophecy concerning Macduff, Macbeth is also promised that he “shall never vanquished be until the Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill shall come.” Later in the play, Macbeth watches his life flash before his eyes as an army of trees marches on Dunsinane. Except they aren’t trees; they are soldiers hiding underneath branches and foliage.

Tolkien was deeply disappointed at this revelation, which installed in him the desire to “devise a setting in which the trees might really march to war.” He did just that in The Two Towers when Middle-earth’s Ents — walking, talking tree-like creatures — besiege Saruman’s stronghold of Isengard to take revenge for the deforestation that fueled the wizard’s war machine.

Shared Englishness

Ignoring Shakespeare is difficult enough for any writer, let alone one as quintessentially English as Tolkien. In retrospect, he may have had more in common with the Bard than he cared to admit. In addition to their mutual interest in the fantastical, both men were deeply connected to the English countryside — a country that gave them a deep appreciation for the simple things in life. For Shakespeare, this manifested in the bawdy humor and the unorthodox wisdom of characters such as Falstaff. For Tolkien, it found expression primarily through the Hobbits, whose humble existence rendered them immune to the corrupting power of the One Ring.