The power of speaking strangely

- We judge people by the way they talk. From an early age, we are taught that certain speech patterns are “bad” English and should be avoided.

- According to sociolinguist Valerie Fridland, such patterns may not follow formal writing rules but offer a means for groups to solidify social identities and connections.

- By understanding this, we can be more empathetic toward people who speak differently from us and appreciate just how innovative language can be.

Don’t use the singular they. Don’t use literally when you mean figuratively. Don’t end a sentence with a preposition. Irregardless isn’t a word regardless of where you heard it. Don’t split your infinitives or dare to utter “between you and I.” And whatever you do, never, ever start a sentence with a conjunction.

Sound familiar? If you’ve spent any time in a classroom or around a fussy grandparent, then you’ve heard someone utter these or similar precepts as the hard-and-fast rules of English. To be fair, it comes from a good place. Teachers instruct in a style of English that they hope will serve students well. Grandparents want their grandkids to grow up into eloquent members of society. Despite their best efforts though, such usages continue to bubble up naturally in our day-to-day speech.

But if such usages feel so natural, then why do they rile everyone from English teachers to stand-up comedians and snooty Tweeters? Are they really that bad, or do they serve some unrecognized purpose? And in labeling them “bad” English, are we unwittingly doing harm where we intend good?

I spoke* with Valerie Fridland, a sociolinguist and the author of the book Like, Literally, Dude: Arguing for the Good in Bad English, to discuss these questions and why we should rethink how we view and value social speech habits.

Kevin: Let’s set the stage. Most books on English try to teach people how to turn their unrefined writing or speech into something proper. The Strunks and Whites of the world. You took your book in a different direction and argue “for the good in bad English.”

What made you want to take that route?

Fridland: I’m a linguist, so I’ve always studied how language actually works. What are the underlying linguistic forces? The articulatory pressures that make language do what it does? I’m also interested in how social forces interact with that. The books you’re talking about, the prescriptive books, are interested in describing how people think we should talk.

I found that when I gave lectures about linguistic topics, people would ask me questions about the things that they notice as bad speech because the prescriptive view has been so ingrained in them. They don’t even think about that as being one view of language. They think about it as the only view of language.

So I thought, “Why don’t I try to write a book that takes both of those views and tries to synthesize them?” We need to figure out the prescriptive view and the descriptive view, put them together, and understand that there are two different ways to look at language. Neither is right or wrong; they are just complimentary in terms of how we use language. If we understand that, then maybe we can be a little more gracious in the way that we look at people that don’t always talk like we do.

Doing as the Romans do

Kevin: I referenced Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, but that book is specifically geared toward the written word. What should readers understand about the written word versus spoken language? How are they different? How are they complementary?

Fridland: That’s a good question because there’s a fundamental difference.

We have to learn to write when we go to kindergarten, but we don’t have to learn to talk that way. A baby is born, and by 12 months, they’re making syllabic utterances. By two years, they’re stringing together sentences. No parent sits down and says, “Okay, we’re going to learn to talk today. Let’s say this sentence.” It naturally emerges.

Now, there are rules for spoken language, but we don’t learn them. They’re implicit in our brains. For example, no word in English starts with LP. It’s impossible. It’s against the rules of English, and if you look worldwide, it’s against the rules of language. There’s something fundamentally unacceptable about it, and it seems to be tied to certain ways our brains work.

Or if I say, “Ted knew John knew himself well,” how do I know that himself refers to John? No one teaches that to a child, yet if you ask them, they always pick John. They don’t pick Ted because there’s a rule in our head that tells us how reflexives refer to antecedents.

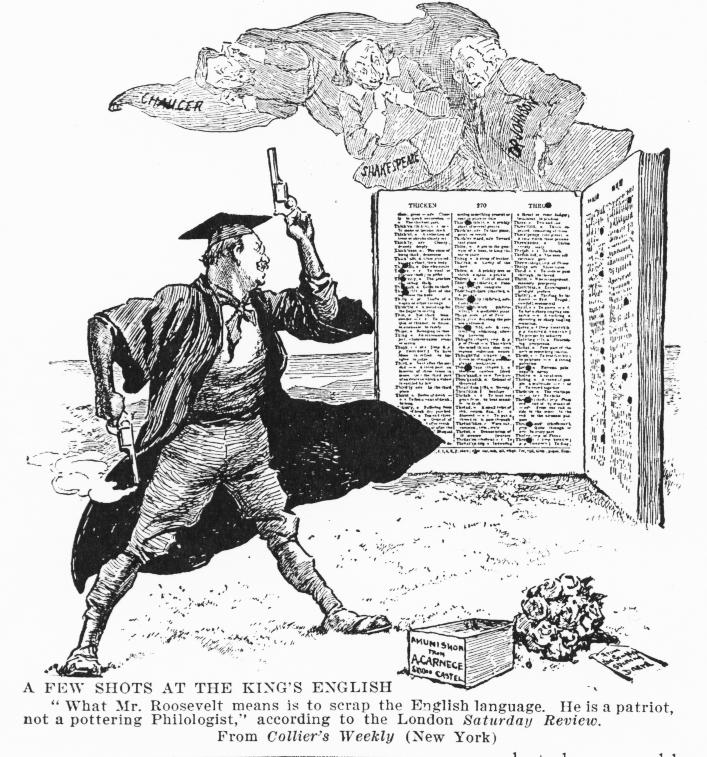

Those are true rules of language. The rules we ascribe to written forms of language are rules that an 18th-century dude thought up — usually comparing English to Latin because Latin was considered an elevated language. That is at the heart of all those grammar books.

Kevin: I remember when I learned that the reason we are told not to split infinitives is that somebody — I think it was an Abbot of Canterbury — said it was improper because you can’t split them in Latin. But in Latin, an infinitive is one word so you can’t split it.

Fridland: It was actually Bishop Robert Lowth. He’s sort of the father of modern prescriptivism. He’s at the root of almost all those rules: Don’t end a sentence with a preposition, don’t split an infinitive, and so on. The funny thing about Lowth is that he was writing a grammar for his son, who was entering school. He wanted his son to learn the rules of Latin because he thought it would help him learn the rules of English.

It became very popular. I think it may be the best-selling grammar book ever. In fact, Lindley Murray, who wrote the grammar books that almost all school children used up until about the 1950s, basically stole all of his ideas from Lowth.

And it was more that Lowth said it’s more elegant to follow the rules of Latin. He never said it was wrong. The same thing about not ending a sentence with a preposition. You can’t do that in Latin, and therefore he said it was more elegant not to. That got misconstrued as being a rule, but if you look at Shakespeare, he ends sentences with prepositions all the time.

Language as power and prestige

Kevin: You mention in your book that men can use strength and economic advantage to secure their social status. Conversely, women have had to rely on more “symbolic resources.” Quote: “Language helps women (and others) negotiate status and a sense of belonging, providing a form of social capital as valuable as fists and finance.”

How does language do that, and why those groups specifically?

Fridland: Basically, people use language to project some identity that’s going to be valuable for them in their lives. This could be upward mobility. If you want to aspire to certain positions, you may adopt the code of those currently in power use. One way to do that is to start dressing as if you’re from, say, London rather than a rural county, right? Part of that style is also language. That would be external prestige.

But a lot of times, people either don’t want or can’t aspire to that because of some facet of their social identities. What’s interesting is we find that people inculcate various types of prestige insofar as what they have access to.

If I’m in a neighborhood and everybody looks like me and talks like me, then that’s going to drive us together. That’s going to give us power socially, and we can manipulate our use of these features because they become emblematic of certain social identities. Language is one way to embody that identity and lay claim to it. We also want to identify with groups that we spend time with.

So, you’re staking a claim as being a member of that group, but you’re also separating yourself from groups outside that may be treating you badly or rejecting you in some way. That has a lot of power because when someone does that — as long as it’s legitimate — it bonds them with others that share that social identity and makes the group much more powerful in the face of an external threat.

Kevin: Makes sense.

Fridland: That’s called “covert prestige.” This prestige is maybe not valued by the larger society, but it is valued by in-group members.

Rather than point to any kind of absolutism, our linguistic likes and dislikes are spurred, instead, by our social needs and wants.

Valerie Fridland

Kevin: How does that connect with assumptions about members of those groups? For example, a female CEO takes on the language patterns of a male CEO because that’s the role she’s supposed to play, but when she does, it clashes with what people expect from female speech.

Fridland: Exactly. Think of Elizabeth Holmes, right? She’s the pinnacle example of what happens when we get strongly identified speech features with one group or another, even though it’s likely that other groups use those speech features, too. It just hasn’t become emblematic of that identity.

Women are expected to be soft, gentle, and not authoritative. Not because they aren’t. I mean, a lot of women use speech features that are very authoritative with children in the household. But in the public sphere, they’ve been put in positions where they can’t use that kind of speech feature because then they are seen as co-opting speech features from another group. They are then judged as being harsh or nasty or bitchy.

Holmes was criticized for her low-pitched speaking voice, and yeah, it is very deep. I don’t know of any studies that have compared her pitch to earlier recordings to establish if that’s actually her speaking voice. But we do have examples of Margaret Thatcher, and she expressly did it because she understood the power of a deeper voice in positions of authority.

That’s because, historically, the people who have populated such posts have had lower, deeper voices. We associate those voices with authority, credibility, authenticity, and leadership. In fact, there’s a ton of evolutionary psychology literature showing that people associate low-pitch voices with those qualities. We also find it in the animal kingdom. Animals will use the deeper pitch of their range when they’re afraid to project a large body size. Humans do the exact same thing; we just don’t have to beat on our chests anymore.

Now, is it legitimately true? No. There’s nothing that says you can’t have a high pitch voice and be powerful in a social sense. But we strongly believe it.

Linguistic fashionistas

Kevin: Speaking of stereotypes, we have another for the upper crust. Like the one you always see in movies: They speak in a certain manner, they live by traditional hierarchies, and they just won’t budge. Then a new person comes along and changes the dynamic.

Fridland: The cockney speaker who’s like, “What you go and do!” [Laughs.]

Kevin: [Laughs.] My Fair Lady, exactly! It seems like what’s happening is that language gets stilted at the top until something rises from the bottom up. Then whatever that is eventually gets stale until something even newer comes up in its place. Could you speak to that?

Fridland: Absolutely. The more power and prestige we have, the less we change our language because our language solidifies as part of that power and prestige. It’s part of a whole suite of things that we model to others.

It’s the same idea as the three-piece suit. You start to dress a certain way because that becomes emblematic of your position. You start to speak a certain way because that becomes emblematic of your position. And the higher you are in social rank, the more likely you are not going to change those features for two reasons.

First, when you are more literate, you elevate the written word and take those speech norms as what you should do. Historically, this is more accurate than today because we have much more widespread literacy, but when language is written down, it’s immovable, it’s immutable, and it’s unchanging. It’s written. So whenever we start to standardize and codify things, which we do when we get to the upper class, it slows down the rate of change.

Second, when you get power and prestige, it is going to behoove you to keep the same norms. Then your language will be the thing to emulate. It separates you from the riffraff — the same way wearing a three-piece suit does, right? It sets us up as having a certain kind of social identity. You stick to that, and then other people dress like you to become like you and not the other way around. Both of those tend to inhibit language change.

When you’re a lower-class speaker, you don’t have those hang-ups. Historically, you tend to be less literate. Even in today’s societies, working-class groups tend to be more oral cultures. They have a lot of oral storytelling, and so things that happen naturally to language over time are allowed to progress more in speech.

And we always have those underlying linguistic tendencies: the things that our brains and mouths prefer. Lower-class speakers won’t prevent that kind of thing from happening in their speech. But when you’re an upper-class speaker, you frown on those kinds of things because they’re different from the written word. We don’t write don’tcha. We write don’t you. Therefore, I have that in my head. That’s the right form, and I’m not going say don’tcha.

Lower-class speakers won’t be inhibited to the same degree. When the focus is on social identity rather than prestige and power, and when I allow that social identity to drive me, then it’s not the language forms per se that are important. It’s the language of connection that becomes important. Informality, casualness, and all of those things tend to be language that emerges naturally from underlying pressures.

Kevin: That makes sense. Whenever I’m editing the transcripts of my interviews, because of that conversational tone, I can’t believe the number of wannas, don’tchas, and dunnos I utter.

Fridland: That’s because it’s your natural speech, right? You’re not spending time regulating your speech. You have to switch to this really high-status speech, which takes a lot of cognitive effort.

Even when you’re upper class, when you go home to talk to your wife and children, you will use that more informal, intimate language. These more informal forms creep into our speech and have for time eternal. That’s how they make inroads into our speech and become the new norms of tomorrow.

Kevin: I love your analogy to fashion. Linguistic fashionistas, as you refer to these groups in the book.

Right now, I’m watching a period piece that takes place during Prohibition. The suits they wore are a little different, but I can still see in them the three-piece suits men wear today. Little has changed in the intervening century. Then compare that to something like the robes of archbishops and popes — which I assume haven’t changed in many centuries.

Fridland: Fashion is a great analogy for language because we’re doing the same kinds of symbolic identity with it. Part of what gives bishops their power is having this unchanging, very uncomfortable-looking outfit on. We instantly identify them as being a member of that group from their clothes, and the formality of it sets them apart from everyday people. That establishes them as having some sort of credibility.

Language is exactly the same. Whether it’s the language of formality or the language of intimacy and connection, language is a sort of uniform we take on.

Being, like, clueless about like

Kevin: Let’s tackle an example of “bad” English: the so-called misuse of the word like.

Fridland: It’s funny because like is everywhere. Even people who don’t like like don’t realize how much they use it until they record themselves and play it back. I’ve been to a bunch of shows, and people will tell me how like grates on them. They cringe when they hear young people using it. Then they’ll say, “Well, it seems like people are using it so often right now.” And I’m thinking, ding!

Kevin: You need a buzzer, right?

Fridland: That would be really funny. Maybe we should do that. A buzzer on a podcast buzzer.

Kevin: Yes. A linguistics podcast where every use of the topic “bad” English gets buzzed.

Fridland: I love it, though you wouldn’t hear what people are saying. It would just be ding, ding, ding, ding, ding.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Fridland: Okay. Like is a discourse marker in most cases where people don’t like it. It could also be a quoted verb, but it has had many different forms and fashions over the years.

If we look at its trajectory over time, many of the likes that we use today, including prepositions and conjunctions, are not original to English. The original like in English came in the early Middle English period. It was a verb meaning “to like.” That was its original form. The prepositional like would be something such as, “He’s like a brother to me.” That didn’t come in until about the 1400s or 1500s.

The conjunctive like, where you connect two clauses, came in slightly after that. So, “He rode his bike like he was on fire.” But the interesting thing about the conjunctive like is that it has been frowned upon pretty much since it came into English. Strunk and White say not to use like as a conjunction. Every new form that’s not the old form is somehow bad.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Fridland: Then around 1600, like starts to be disconnected from being a syntactic or grammatical function — like a preposition or conjunction — and it takes on a more pragmatic meaning where it’s used to express a general similarity or comparison or approximation. So, “He was like a brother to me” becomes “He’s, like, a brother to me,” which becomes “Like, he’s a brother to me.” The comparison that it’s setting up gets separated.

The discourse marker like — the one either at the beginning of a sentence or stuck in the middle — projects some sort of emphasis or focus. So, I could say, “He’s like 12 years old,” which means he’s about 12 years old. It’s a one-to-one substitution for about. Or I could say, “I was waiting, like, 20 hours for you.” Here, I’m being more emphatic. I didn’t actually wait 20 hours, but it felt like it, and I’m pissed. Those are discourse marker uses.

But if I say something such as, “I was like, ‘I don’t think I’m going to go,’” then I’m quoting what I was thinking or saying. That’s actually a quotative verb. People don’t separate the two, but they are completely different. The discourse marker is actually about 300 years old. We find it in transcripts from the 1700s in British speech. The quotative like is pretty new to the 20th century. We don’t start seeing it until about the 1950s.

Kevin: Who were the linguistic fashionistas that brought this like into the language?

Fridland: It’s hard to tell. Back in the 1700s with the discourse marker, we don’t really know who was using it mostly. But in modern American speech, it is certainly young women who have projected like into the national consciousness. Their use of like really came about in the 1980s and 1990s where it was a Southern California feature. It seems to have been highlighted by this valley girl lifestyle and projected into mainstream culture by the Moon Unit Zappa.

The reason for that is not because young women are vapid or stupid. It’s because they have long been at the forefront of linguistic innovation. Language is more powerful for them in expressing social relationships and meanings than it has been for men.

As we talked about before, men get more value from the same old, same old. Women don’t. They get that from language because they have not traditionally been in those positions of power. Historically, they have also been less literate and less tied to formal conventions of speech and so establish a connection through colloquial language — whether it was in spinning circles, at the market, or in high school today.

Language is social currency for women in a way that it isn’t for men, and social currency comes from not doing the same thing everybody else is doing.

While those forms are still new, we start to associate them with women’s speech because they’re the ones that introduce them. But they’re also the parents and caregivers. So whatever’s new in their speech for one generation becomes basically what everybody does in the speech of the next generation. And by that time, a new norm is established and no one notices it anymore. But while women are still at the forefront of it, they stand out and often get scolded because of it.

Kevin: In this case, the Clueless stereotype.

Fridland: Yes. It’s young women because once you hit about 20, you tend to not have the same ability to innovate in language anymore. Partially that’s because there’s less value in it for you. Once you go into the workforce or become a parent, there’s more pressure for you not to change your speech. But also, cognitively we don’t seem quite as able to do these really low-level distribution analyses that we do when we’re kids.

So, it’s almost always young women that we find innovating — just like young people, in general, are almost always the innovators. Their brains are wired for it.

Viewing the new and distinctive as a threat to our linguistic future, we treat it as something negative, something divisive, but instead it is a powerful testament to our adaptive, innovative, and creative abilities.

Valerie Fridland

Finding the good in “bad” English

Kevin: When I was reading your book, I kept thinking about how the internet has given so many people a means to not only get their speech out there but also connect their language stylings with those of different groups.

How do you see technological trends influencing language moving forward?

Fridland: The internet is a unique thing that we haven’t had a lot of experience with. It’s only been around for 20 years in the form it has today. Texting language is the same way, and it’s a weird hybrid between spoken language and written language. It has the informality of the spoken context, but it has formality in that it’s through writing.

The thing is that we don’t find language change usually transmitted through media. We find language change transmitted through true, authentic connection. What drives our ability to examine distributions in people’s speech and assign it social meaning is true interaction where we understand in a particular context against some sort of backdrop of familiarity.

When it’s devoid of that context, it’s hard for us to do that. If you watch a television show with British English speakers, you don’t suddenly start speaking with an authentic British accent because you’re not part of that community. You don’t actually know the norms for that community.

So the role of the internet and spreading language is fairly superficial. It is going to be mainly vocabulary. Vocabulary gets spread easily through media. So, learning to say rizz for charisma becomes this overnight viral sensation, but then it dies out quickly. I don’t think anybody says rizz anymore because it’s so quick and fleeting.

Now that said, what will change are things like dropping -ly off of adverbs because those are things that are pretty easily modeled. If someone cool is doing it, someone who is socially influential, then people will probably start to mimic that because it’s a fairly easy thing to acquire, and it’s already something that’s an underlying tendency in our language anyway. What I think social media will do is propel underlying changes that are already existing at some level in people’s speech because they are emulating somebody that has higher status as a social influencer.

Kevin: Thank you for a wonderful conversation. I learned a lot and really enjoyed reading the book. Is there anything you’d like to add? Some concluding thoughts you’d like to leave our readers with?

Fridland: One of my goals in this book is to try to help people be more empathetic when they hear other people talk and also when they hear themselves talk.

What I think is the crucial takeaway of the book is that dislike and bad are two different things. Dislike just implies that we have a particular fondness or non-fondness for something. That’s okay; there’s no value judgment there. But when you say something is bad, that’s making a moral judgment, and there are consequences. If you feel like you’re speaking badly, you’re going to be more insecure about it.

If those moral associations are made about people that speak differently than us, that can have significant societal consequences because they’re often tied to cultural moments and social power. Those who have less power socially are often those whose speech we call bad. This inhibits them from job opportunities. It inhibits them from social opportunities. It makes us judge them as less competent and valuable to society in general.

And so, I think it’s important to understand that you can dislike a speech feature without devaluing the people who use it. That’s the big takeaway of the book.

Kevin: I really appreciate that. Perfect wrap-up. Where can we find you online if they want to learn more about language?

Fridland: I think the best place is probably my website, valeriefridland.com. I also write a monthly blog for Psychology Today called “Language in the Wild.”

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

*This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.