The invasion of Antarctica: Non-native species threaten the world’s last wilderness

- Antarctica is the world’s most isolated, extreme, and pristine continent.

- Climate change and human activity have facilitated the establishment of 11 non-native invertebrates in Antarctica, threatening vulnerable indigenous species not adapted to competition.

- Antarctic microbial communities are also vulnerable to human presence, with each person visiting the continent bringing millions of novel microbes along.

Very few species call Antarctica home. Physically isolated from the rest of the world and home to frigid weather, the Antarctic peninsula is inhospitable to all but the most cold-hardy species.

Considered by many biologists to be the last pristine wilderness left, the Antarctic’s unique isolation and extreme weather have sheltered it from human impacts that have largely devastated natural habitats in the rest of the world. However, the geographic isolation and extreme temperatures protecting Antarctica are under threat.

Climate change and human activity

Climate change has taken Antarctica’s once intolerable climate and turned up the heat, with air and water temperatures steadily rising to levels that many more species find accommodating. With rapid ice shelf collapse, new benthic floor habitats are created, opening new territory for invaders. In this changing Antarctica, many more plants and animals could feasibly establish populations if they could make it across the water. And they can, with help from humans.

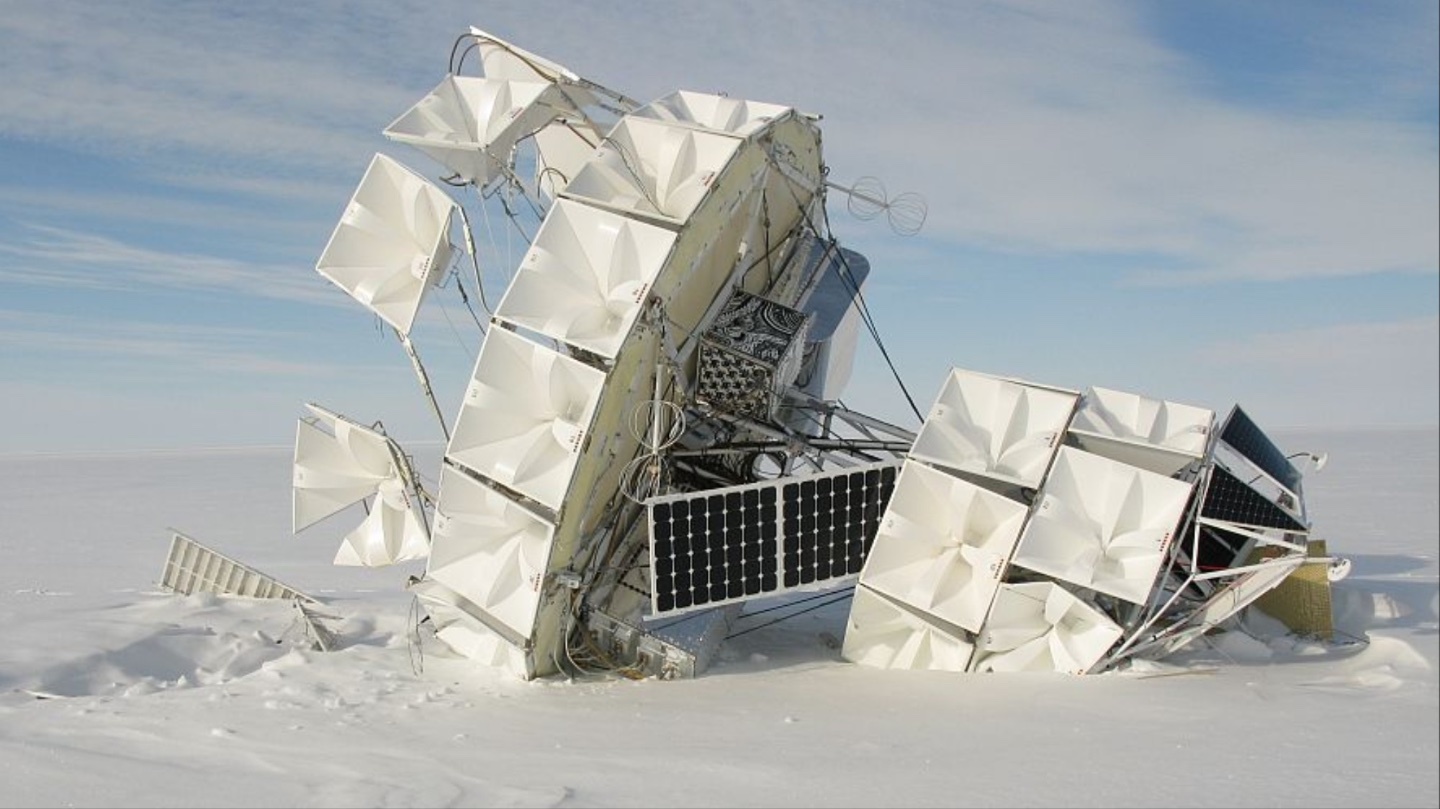

No amount of geographic isolation on Earth is a match for the combustion engine. Since the mid-1950s, human presence on the continent has grown rapidly. As we migrate to the continent for research and tourism, our ships and vessels bring along unknown passengers: microbes hitch a ride within our gut and waste, mice and plant seeds survive in food stores, and mussels cling onto the hulls of ships

The interactive effects of a warming climate and increased human activity to and from the continent are eroding Antarctica’s natural biological barriers. The result: more and more non-native species slipping through the cracks.

Antarctica’s indigenous species are used to being alone. With low diversity but high endemism, species are adapted to the singular climate and life on the continent and are no match for any outside competition. In what could be a perfect storm, non-native species have the potential to completely disrupt the last remaining wilderness on the globe — all because they hitched a ride with humans.

11 new invertebrates call Antarctica home

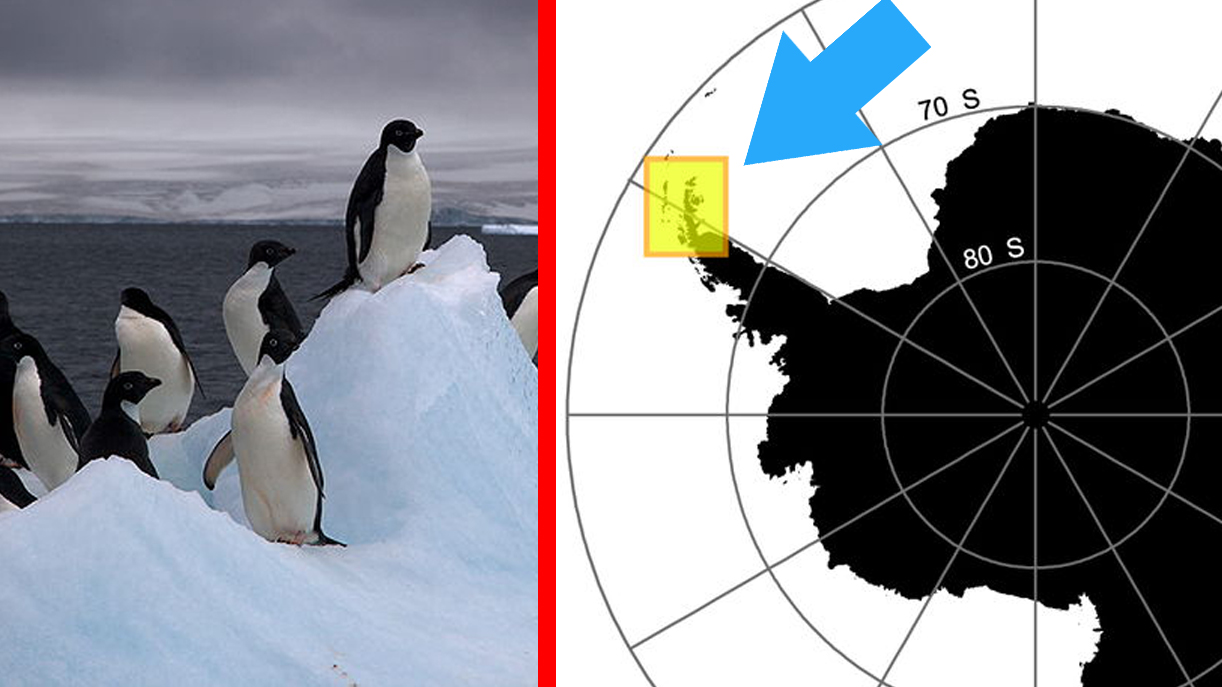

So far, 11 invertebrate species have been found in the Antarctic, including springtails, mites, and midges. Most have managed to establish small populations in the warmer parts of Antarctica near research stations. These species likely were transported to Antarctica by attaching to the ships that bring visitors, cargo, and supplies.

Fortunately, most of these species do not pose serious threats. Other non-native species have been seen on the peninsula but have failed to establish robust populations. The pervasive annual grass Poa annua had established a population on the continent, but it was eradicated. (However, small populations persist on King George Island.) Over 50 marine taxa have been observed on vectors such as ship hulls but have not created stable populations.

Even COVID made it to Antarctica

In such an extreme environment, many of Antarctica’s permanent inhabitants are microorganisms that can tolerate harsh conditions. Conservationists, in general, don’t pay much attention to microbes. Microbes, in general, tend to receive far less protection than large mammals or birds. But endemic microbes are at severe risk; each human passenger that travels to the continent houses millions of non-native bacteria.

In contrast to the introduction of non-native plants and animals, the impact of introducing microbes is not immediately obvious. Many practices standard in Antarctica, like dumping untreated wastewater into the ocean, represent huge opportunities for introducing non-native microbes. Bacterial invaders have the potential to spread exceptionally quickly since they can exchange genes with native bacteria, including those responsible for antibiotic resistance. This will create more virulent native bacteria, threatening animal hosts and fundamentally changing the endemic and diverse Antarctic microbial fauna.

We have already detected human-derived Escherichia coli, known to cause disease in seals and birds, in the Antarctic. Non-native resistant bacterium Serratia marcescens was detected in guano from penguin colonies near tourist destinations, indicating an interaction between the non-native bacteria and the indigenous bird. One research station even experienced a COVID outbreak. Without further mitigation, there is a high likelihood that humans will transmit one or more diseases to local wildlife.

How to protect Antarctica

While it is inevitable that the climate will continue to warm and human visitation will increase, international efforts can step in to help bolster Antarctica’s weakening natural protections.

The Antarctic Treaty is a document used to establish and regulate international relations within Antarctica. Its Environmental Protocol identifies priorities and methods to respond to environmental threats to the continent. As part of the Protocol, all 54 member nations unanimously voted to prioritize non-native invasions, with increased funding earmarked for scientific efforts aimed at identifying potential invaders and creating mitigation protocols.

The tourism industry also must get on board with more vigilant cleaning of clothing, equipment, machinery, fresh food, and other cargo where invaders can hide. Finally, given the vulnerability of Antarctica to microbial invasion, dumping untreated wastewater — a practice currently allowed under the Antarctic Treaty — should be stopped. The issue has also caught the attention of scientists, who argue that it isn’t too late to protect Antarctica. In a paper published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Dr. Dana M. Bergstrom identifies major threats to Antarctica and proposes ways to mitigate them. Dr. Bergstrom argues for a multiple-barrier approach to preventing invasion. By identifying and monitoring the paths propagules take to get to the island, assessing which sites are at higher risk for invasion, and swiftly responding to any detection, we can guard the Antarctic.

We have already had some successes. Rapid response in 2014 eradicated the non-native invertebrate Xenylla found in a hydroponics facility in east Antarctica.

Fortunately, Antarctica’s challenging climate means no significant populations of harmful invasive species have taken hold. However, with more than 5,000 residents in the summer*, increased tourism, and an inevitably warming environment, the challenges will mount in our effort to preserve the Antarctic wilderness.

*Editor’s note: A previous version of this article referred to 5,000 research stations. The correct statistic is 5,000 summertime residents.