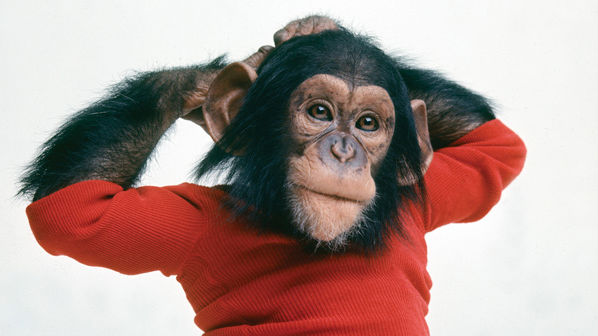

Watch chimps use insects as medicine on one another

- Many animals practice what appears to be self-medication for a number of problems.

- A new report finds that chimps use insects on wounds.

- Some of the cases appear to demonstrate prosocial behavior, with chimps attempting to heal each other.

Many animals, including dogs, cats, parrots, butterflies, and chimps, engage in zoopharmacognosy — animal self-medication. Each of these creatures, and many others besides, appear to self-medicate by eating or rolling around in substances of little nutritional value but which appear to provide certain health benefits to the animal.

For example, you have probably seen your dog eating grass. This isn’t because your pet has turned vegetarian but because eating the grass can solve stomach problems by either inducing vomiting or promoting regularity. Other animals, such as parrots, will eat clay to help resolve harmful substances from their stomachs. It is hypothesized that one of the reasons cats love catnip is for its use as an insect repellent.

A new study adds another possible example of animal medicine to the list. It also suggests that the creatures involved can be empathetic and prosocial.

Chimp caretaking

The new research, published in Current Biology, marks the first time that the application of insects to an individual animal’s body as a kind of self-medication has been observed.

The study reveals that chimps with open wounds apply an insect to themselves in a pattern that appears to have little variation across the observed population. The insect is captured, immobilized by squeezing it between the lips, rubbed on the wound at least once, and then disposed of.

In a few cases, chimps are using the insects to tend to the wounds of other chimps. For instance, an adult female chimp named “Suzee” by the researchers caught an insect and used it on the wound of her adolescent son “Sia.” In the clip, she can be seen reapplying the insect to the wound two more times for good measure. Another case reported in the study was between two unrelated adults, with one applying the insect to the other.

So far, the scientists know neither which insect the chimps are using as medication nor if the treatments actually work. The observations do, however, add yet another example to the ever-growing list of known prosocial behaviors seen in our closest evolutionary relatives. The authors of this study note that many behaviors shown by chimps, such as “territorial patrols, coalitionary aggression, and hunting,” seem to suggest a drive to cooperation, and that requires an ability to engage in sincerely prosocial behavior. However, many scientists remain unsure, as it is difficult to know if the chimps are truly practicing what we would call empathy when they engage in these behaviors.

As highly social animals, it would benefit chimps to be capable of at least some form of empathy. Many chimp behaviors, such as social grooming, exist to help secure social bonds and make living together possible. Perhaps using insects to heal each other’s injuries serves a similar purpose.