Dinosaurs got sick, too — but from what?

- A team of American researchers has uncovered the first evidence of respiratory infection in sauropod dinosaurs.

- Studying the way diseases developed in dinosaurs is difficult yet necessary to help us understand the evolution of infectious diseases.

- Many of the pathogens that afflicted dinosaurs are still around today.

In 1990, archeologists recovered an extraordinary set of dinosaur fossils from the Morrison Formation in southwest Montana. It wasn’t the discovery itself that surprised the archeologists; excavations from the Formation, a slab of sedimentary rocks from the Jurassic period that stretches from Montana to New Mexico, had already produced dozens of other diplodocid fossils, many of which were largely complete.

What made these fossils so extraordinary was their distinct morphology. While they clearly belonged to a diplodocid — a group of sauropod dinosaurs characterized by their long tails and even longer necks — researchers have yet to determine the exact species. The set of bones — a complete skull and seven cervical vertebrae — also showed abnormal bony protrusions that had not been encountered in any other diplodocids.

After taking a closer look at the protrusions, a team of researchers led by the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum’s paleontology director Cary Woodruff came to the astonishing conclusion that they might be ossified signs of a 150-million-year-old respiratory infection. Their findings, published in Scientific Reports, advance our understanding of ancient diseases.

A remarkably sick sauropod

The protrusions were found on the vertebrae, in areas where the bones would have been penetrated by air sacs, which are parts of the respiratory system that are constantly being filled with air. Air sacs are an important part of the respiratory systems of birds, though many avian and non-avian dinosaurs like sauropods had them as well. In sauropods, they may have helped to regulate body temperature — a vital function considering large animals lose heat less quickly than small ones.

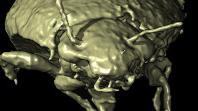

CT scans revealed the unusual protrusions on the diplodocid’s neck bones were made of abnormal bone and that this abnormal bone had likely been formed in response to an infection in the animal’s respiratory system. “This would have been a remarkably, visibly sick sauropod,” one of the researchers, University of New Mexico Research Assistant Professor Ewan Wolff, told UNM Newsroom.

“We always think of dinosaurs as big and tough,” Wolff adds, “but they got sick. They had respiratory illnesses like birds do today, in fact, maybe even the same devastating infections in some cases.” Wolff brings up an interesting point. Because dinosaurs are long extinct and bear little resemblance to today’s animals, people tend to think of them as fantastical creatures that probably weren’t susceptible to the myriad of diseases affecting us humans.

This was, of course, far from the case. Just like any other living creature, dinosaurs got sick as well. Sometimes, they recovered from their illnesses. At other times, they did not, and as their muscles and organs corroded, so too did the bacteria and viruses that caused their deaths. Consequently, evidence of ancient diseases mainly survives in the form of scar tissue. But while such evidence is scarce, experts have still managed to develop a detailed understanding of dinosaur health issues.

Evidence of avian and fungal infections

Due to the nature of fossilization, there is no way of knowing how a disease or infection would have behaved inside the body of a dinosaur. Instead, researchers have to look at how these conditions affect animals that are closely related to dinosaurs, like reptiles and birds. Only once they have figured out that part can they ask themselves how the unique biology of dinosaurs might have amplified or suppressed certain symptoms.

Woodruff and his team speculate that the diplodocid’s respiratory problems were caused by a disease similar to aspergillosis, a fungal infection caused by inhaling particles from a mold that grows close to the ground. While aspergillosis rarely affects humans, it poses a significant threat to birds; in the span of a week, an outbreak in Idaho in 2006 led to the deaths of more than 2,000 mallards after one of them happened to eat some moldy grain.

Given that aspergillosis still exists today, researchers have some idea about how such a fungal infection might have affected diplodocids. Woodruff’s article declares that the dinosaur — if infected — would have suffered from pneumonia-like symptoms like fever and weight loss. Breathing difficulties would have emerged in an attempt to wall off the fungus. Since aspergillosis can be fatal in birds if left untreated, perhaps those same odds applied to dinosaurs as well.

While dinosaurs were a highly diverse group of animals, some forms of infection could easily transfer from one species to another. A study from 2009, for instance, analyzed erosive lesions on the jaw bones of Tyrannosaurus rex fossils. Although these lacerations had previously been attributed to bite wounds, the study suggests they may have been caused by trichomoniasis, a parasitic infection that was commonly found in avian dinosaurs.

Why dinosaurs rarely developed cancer

Aside from viral infection, dinosaurs also suffered from cancer. Similar to infections, the most obvious signs of cancer disappear when an organism dies and its cells degenerate. Every now and then, however, a surprisingly well-preserved fossil is found that can dispel some of our most pressing questions. Only a few years ago, researchers from Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum and McMaster University discovered traces of an aggressive bone cancer in the lower leg of a centrosaurus.

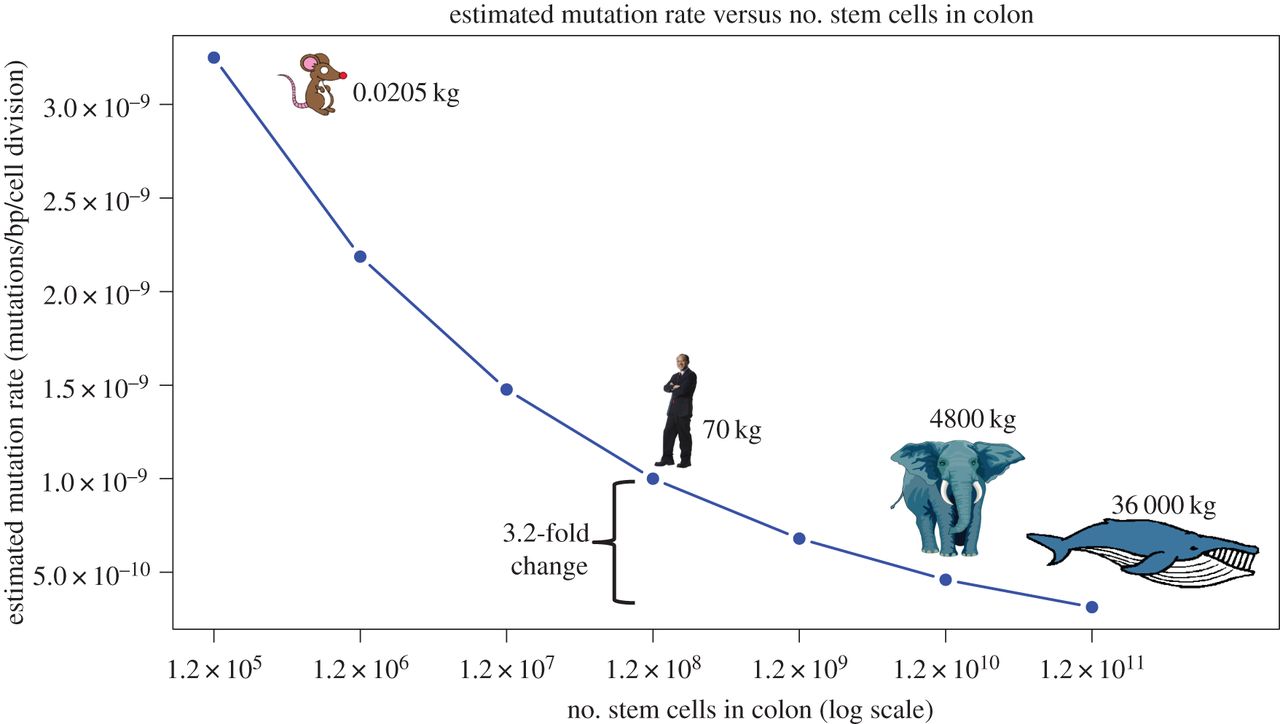

While dinosaurs were indeed susceptible to cancer, the disease seems to have affected them far less frequently than, say, us humans. At first, this seems paradoxical. Cancer, after all, is nothing more than abnormal cell growth. As such, it follows that the higher an organism’s cell count, the greater the chance that organism will one day suffer and perhaps even succumb to the incessant growth of a malignant tumor.

And yet, this is not the case — large-bodied animals like whales and elephants, for example, develop cancer far less frequently than small animals like rodents. Why this is the case is still uncertain, though at least one study has suggested that larger animals might possess the biological means necessary to “combat” cancer.

Woodruff and his team relied on these studies to rule out the possibility that the unusual bony protrusions in their diplodocid specimen were remnants of ossified cancer cells as opposed to scar tissue from an infection. Because the lifespan of long-necked dinosaurs was relatively short when compared to their body size, the researchers suspect that diplodocids may have “simply negated the need to evolve resistance to cancers” and “evolved some more rudimentary forms of cancer suppression.”

The future of dinosaur pathology

Studying the evolution of diseases across deep time is as difficult as it is rewarding. Many bacteria and viruses that shocked the immune systems of dinosaurs are still around today, and by analyzing the effects that these pathologies had on their hosts — not to mention the tactics that their hosts employed to deal with them — we may learn something about how to fight those illnesses in the present.

What’s more, Woodruff and his team showed that dinosaur fossils can tell us a great deal about the evolution of immunity as well as the history of infectious disease — two fields of study that became of international concern after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. Like humans, dinosaurs lived in densely populated ecosystems that were teeming with pathogens, and we have only just begun to understand how these pathogens may have contributed to their demise.

As new technologies are being invented, researchers will hopefully have an easier time looking for traces of illness and infection in million-year-old fossils. Speaking to staffers from the University of New Mexico newsroom, Wolff mentioned that collaboration between experts of different disciplines — veterinarians, anatomists, paleontologists, and radiologists — will also help researchers ascertain “a more complete picture of ancient disease.”