Remembering Peregocetus pacificus — modern whales’ otter-like ancestor

Reconstruction by A. Gennari in Lambert et al., 2019

- Researchers discovered a fossil of a four-legged, amphibious whale off the coast of Peru.

- The fossil is among the oldest of its kind at 42.6 million years old, and its skeletal structure offers insights into the transition of whales back into the ocean.

- One of the more exciting findings is that this species suggests that these ancient whales came to South America by swimming across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa and spread across the globe from there.

The evolutionary path of whales has traced a rather circuitous route. First, their ancient ancestors inhabited the oceans, like all life on Earth did. The ocean was a pretty good spot; water provided protection from the sun’s rays, there was no concern about drying out, and sources of energy were plentiful. Animals stayed in the oceans for at least 600 million years.

At the earliest, life exited the oceans and adapted to life on land about 500 million years ago, though estimates vary. Eventually, some of this life became part of the clade Laurasiatheria, from which a common ancestor gave rise to giraffes, zebras, hippopotamuses, and — although it seems peculiar — whales. Unlike the other members of their clade, the ancient whale decided that life on dry land wasn’t all it cracked up to be and returned to the ocean; there, they eventually lost their legs and grew to become the behemoths we know them as today, though their time on land means they still need to breathe air.

A paper published in Current Biology on April 4 provides a new glimpse into whales’ transition back into the oceans. Olivier Lambert and colleagues discovered an exciting fossil of a new species — a four-legged, amphibious whale that the researchers dubbed Peregocetus pacificus. Not only is this new fossil the most complete one of an ancient whale found outside of Indo-Pakistan, it’s also the first quadrupedal whale skeleton found in the entire Pacific Ocean. What’s more, it’s likely one of the oldest such specimens ever discovered — this skeleton is 42.6 million years old.

Unlike the passive giants we’re familiar with, P. pacificus didn’t leisurely filter krill through baleen. Instead, it’s elongated snout and sharp teeth enabled it to prey on relatively large creatures, likely bony fish. But its anatomy suggests an even more interesting life for this species, and it has to do with the species’ name, “Peregocetus pacificus,” which means “the traveling whale that reached the Pacific Ocean.” This is for good reason: P. pacificus got around.

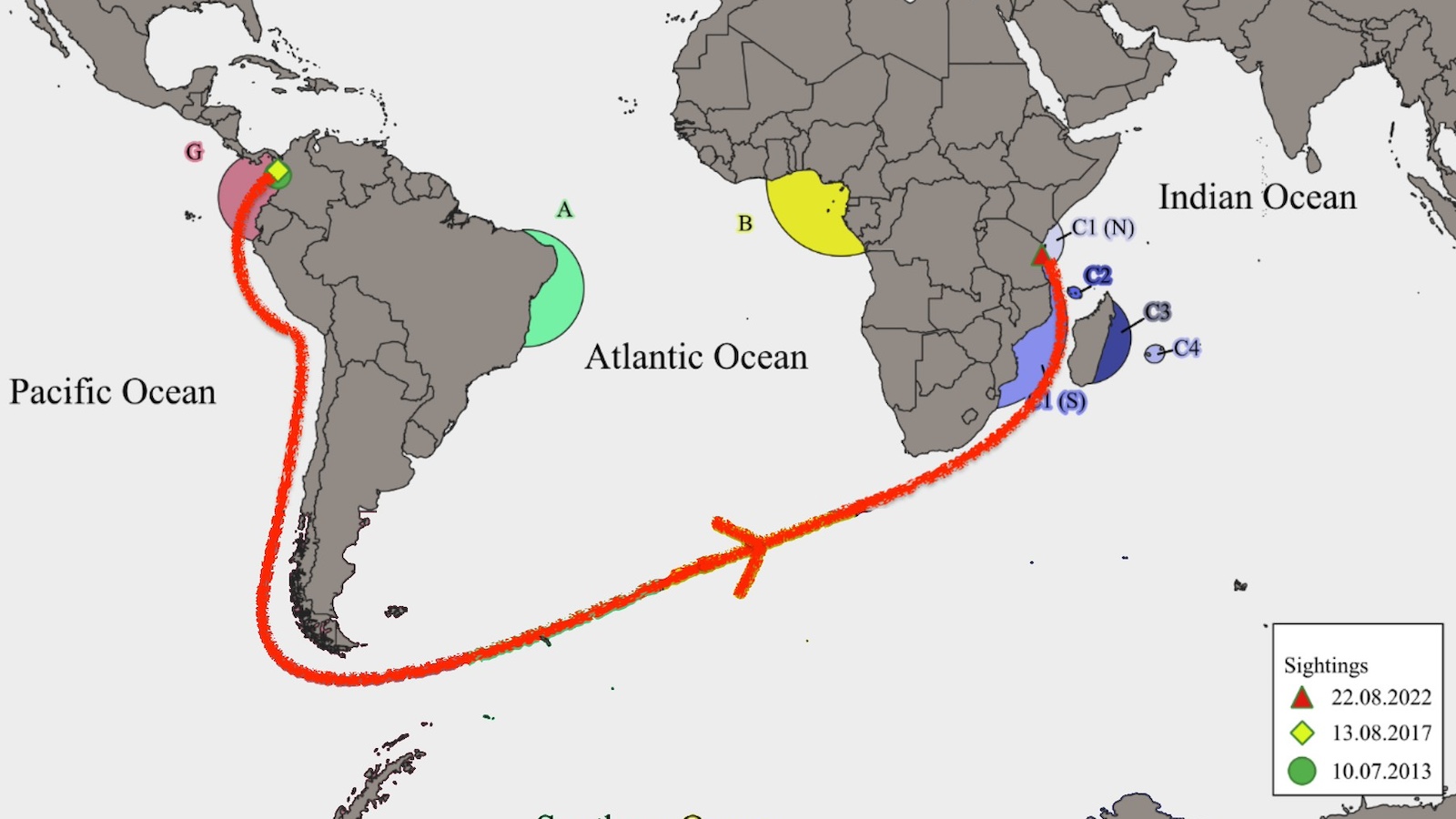

This figure shows how ancient whales spread across the globe. The circular dot on the right represents the suspected origin, while the star on the left represents the site where P. pacificus was found. Note the transition from Africa to South America, marked by the roman numeral III.

Llambert et al., 2019

Far-flung relations

This species of whale was about four meters long and possessed small hooves, meaning it could easily walk on land if need be. Its skeletal structure suggests that it probably swam the way otters do, by undulating its body and tail while simultaneously paddling with its hind limbs.

Its features are similar to those found from other ancient whales in the midst of their transition to the oceans. But these other fossils were found in West Africa, Morocco, and Nigeria, while P. pacificus was found near Peru. What business does this new species have sharing features with fossils found a continent away?

The researchers suspect that P. pacificus was capable of swimming long distances, distances so long that they could cross the Atlantic Ocean from Africa to eastern South America. This would have been an easier feat then than it is today. The two continents during P. pacificus‘s day were more than two times closer than their modern distance, and the current would have helped them move westward.

From there, P. pacificus probably hugged the South America coastline, traveling north, crossing over Central America (which was underwater during this period, the Middle Eocene), and then moving south again along the South American coast. Ultimately, this particular specimen found its way to the Playa Media Luna in Peru, died, and was dug up 42.6 million years later.

Behold, the tiny hind limbs (at the left below the tail) of the early whale Dorudon.

This finding helps confirm that modern whales once walked on land alongside other ungulates, such as ancient camels and deer. Over time, species like P. pacificus found it better in the oceans. Gradually, they lost hind legs, and their fore legs became flippers. Today, some whales still sport vestigial hind legs concealed inside their bodies. They grew to enormous sizes, lost their teeth, and replaced them with baleen. Seeing P. pacificus‘s fossil offers us a snapshot of a moment in time 42.6 million years ago, demonstrating the remarkable adaptability of life on Earth.