Capuchin monkeys have refined their tool use over 3,000 years

NELSON ALMEIDA/AFP/Getty Images

- Archaeologists dug into the ground of an area of a Brazilian national park known to be frequented by capuchin monkeys.

- They found that over the past 3,000 years, the stone tools that the monkeys use have evolved and changed, marking the first time this kind of development has been observed in a non-human species.

- The findings underscore the intelligence of the capuchin monkeys and serve as a parallel to our own development.

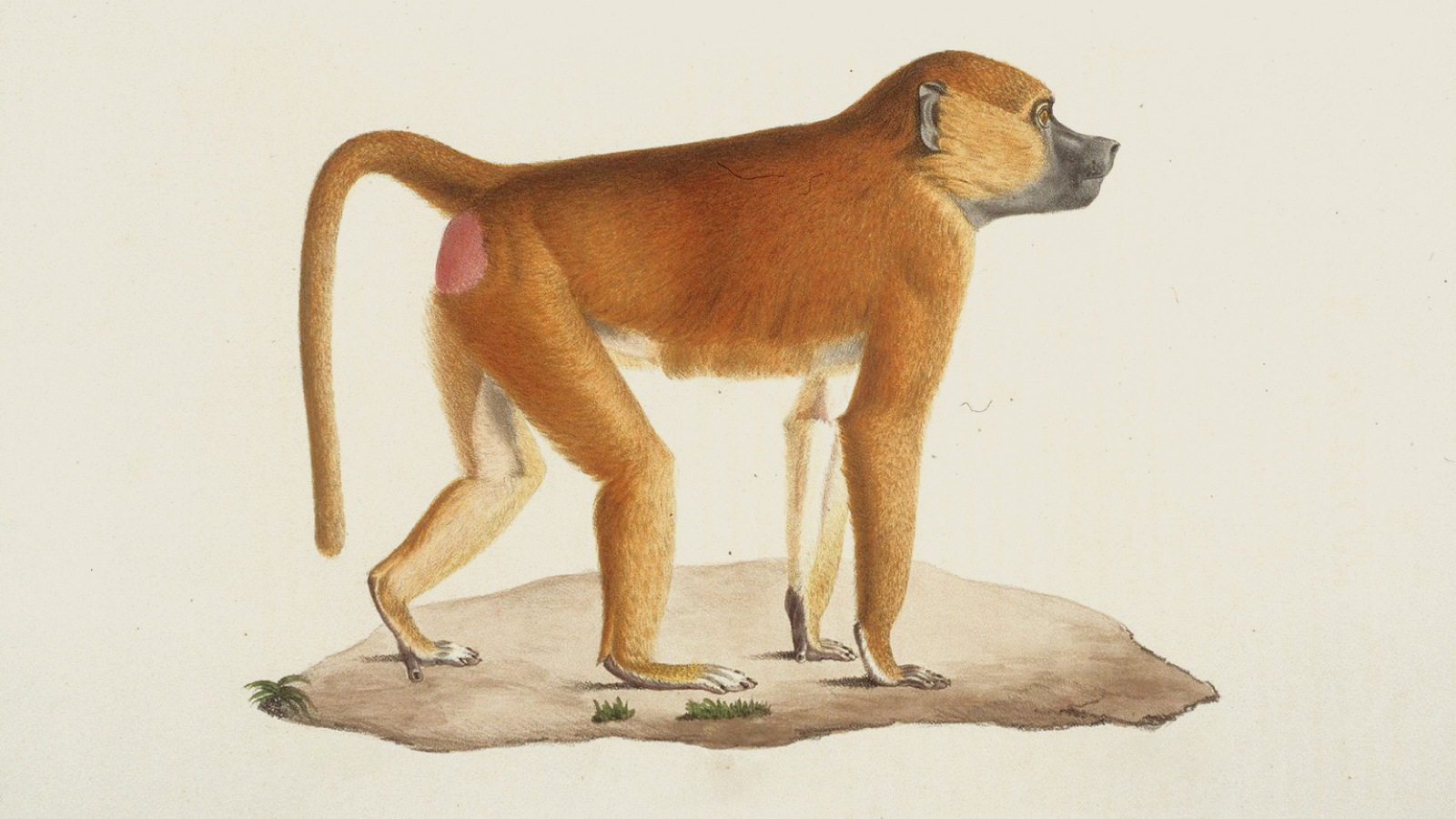

As it turns out, humans might not be the only species that’s developing new technology. Researchers traveled to a popular spot in the Serra da Capivara National Park in Brazil known as Caju BPF2, an open-air site within the Baixão de Pedra Furada (BPF) valley. The spot, however, isn’t a popular destination for tourists — its most frequent visitors are Sapajus libidinous, or capuchin monkeys.

One of the defining traits of the capuchin monkey is its innovative tool use. Because of this, capuchins are often characterized as among the more intelligent primates. At the Caju BPF2 site, capuchin tool use mainly features the use of quartzite stones for a variety of tasks, such as cracking nuts, processing seeds and fruits, stone-on-stone percussion, and sexual displays — specifically, female capuchins flirt by throwing rocks at potential mates. While the use of tools is a unique feature of an animal species alone, it appears that the capuchins’ use of stone tools has developed over the last 3,000 years. Researchers believe the type of stone tools the capuchins use are changing depending on whether the monkeys are eating soft, low-resistance foods like seeds or hard, high-resistance foods like cashews.

“It’s likely that local vegetation changes after 3,000 years ago led to changes in capuchin stone tools,” says archaeologist Tomos Proffitt, who co-authored the paper. Alternatively, it’s possible that different capuchin groups that occupied the site over time may have had different food preferences and correspondingly different techniques for processing them.

Examples of the capuchin monkeys’ stone tools with typical percussive damage.

Photo: Falótico et al., 2019

Analyzing the stone tools

To determine this, the researchers dug several feet down and recovered stones that they referred to as “hammerstones” or “anvils.” These could be identified by their sizes, since they tended to be larger than the pebbles naturally found in the ground, and they have small impact marks covering their surfaces. It was clear that these were specifically capuchin tools and not those of ancient humans, since humans tend to use sharpened, knapped stones instead of conveniently shaped natural rocks.

Then, the researchers radiocarbon-dated the stone tools to determine their age. Altogether, the tools came from four distinct periods in capuchin history, with a maximum age of around 3,000 years. By comparing the periods with the stones’ characteristics, the researchers were able to identify what tasks the capuchins were using these tools for.

The earliest tools were small and covered in many impact marks, suggesting that they were used for processing many small, soft foods, like seeds. Then, the tools grew larger, indicating that the capuchins had shifted their diet to one consisting of hard-shelled nuts and fruits. Beginning about 100 years ago, the stone tools shifted to a moderate size, which modern capuchins use to crack open cashews.

What’s the significance?

It might seem like pounding rocks against rocks can hardly be considered tool use or that the fact that these stones changed size over time isn’t significant. However, using rocks to pound things is the first example of human tool use, too. What’s more, West African chimpanzees have been observed using large, heavy stones to crack tough-shelled nuts and small stones to break softer-shelled nuts, lending credence to the researchers’ theory that the size variation of the capuchin stone tools corresponded to a change in diet.

The real contribution of this study, however, is that it’s the first to record an on-going variation in non-human tool use. West African chimps may use different tools for different tasks, but there’s no evidence that this has changed over the past few millennia. To Proffitt, this is an exciting find.

“This capuchin excavation shows that this species of primate in Brazil has its own individual archaeological record,” he told National Geographic. “They have their own antiquity to their tool use.”