Sleepwalking is the result of a survival mechanism gone awry

Last night, most of us went to the safety and comfort of our beds before drifting off to a night’s sleep. For some, this was the last conscious action before an episode of sleepwalking.

Recent research from Stanford University shows that up to 4 per cent of adults might have had such an experience. In fact, sleepwalking is on the rise, in part due to increased use of pharmacologically based sleep aids – notably Ambien. Often, the episodes are harmless. Take for example, Lee Hadwin, a Londoner whose professional artistic talent seems to be present and activated only while he sleeps.

Sometimes, of course, sleepwalking is dangerous. Somnambulists are in an irrational state during which they could harm themselves or others. Some extreme examples include the instance of the English teenager who in 2009 jumped eight metres out of her bedroom window, or the case of Kenneth Parks in Toronto, who in 1987 drove 23km and murdered his mother-in-law, all apparently while sleeping. Parks committed the act – if that’s the right word – despite an agreeable relationship with the victim and a lack of motive.

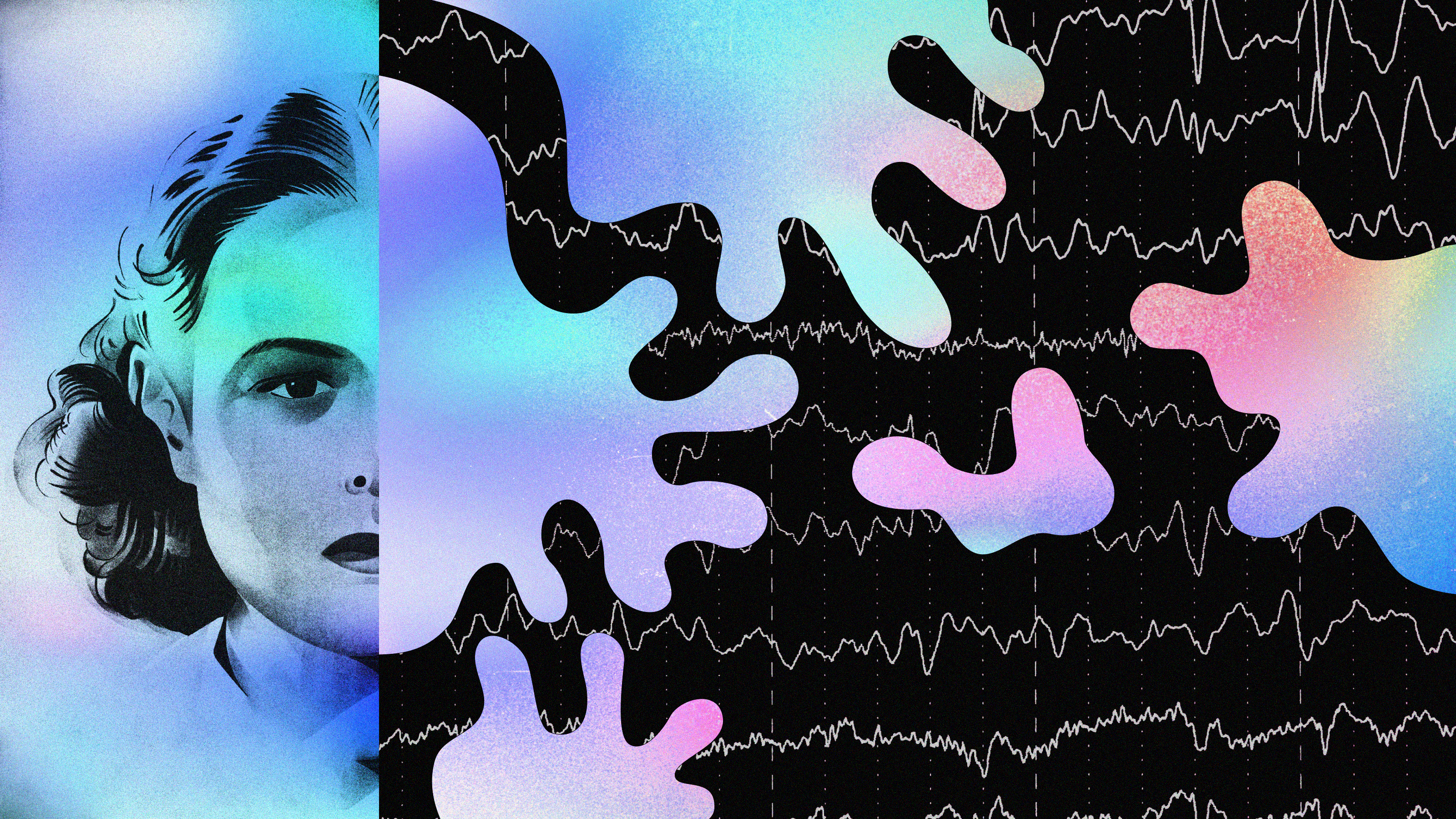

Why do some enter into such a potentially harmful state during sleep? One answer comes from studies suggesting that ‘sleepwalking’ might not be an appropriate term for what is going on; rather, primitive brain regions involved in emotional response (in the limbic system) and complex motor activity (within the cortex) remain in ‘active’ states that are difficult to distinguish from wakefulness. Such activity is characterised by ‘alpha wave’ patterns detected during electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings. At the same time, regions in the frontal cortex and hippocampus that control rationality and memory remain essentially dormant and unable to carry out their typical functions, manifesting a ‘delta wave’ pattern seen during classic sleep. It’s as though sleepwalking results when the brain doesn’t completely transition from sleep to wakefulness – it’s essentially stuck in a sleep-wake limbo.

‘The rational part of the brain is in a sleep-like state and does not exert its normal control over the limbic system and the motor system,’ explains the Italian neuroscientist Lino Nobili, a sleep researcher at Niguarda Hospital in Milan. ‘So behaviour is regulated by a kind of archaic survival system like the one that is activated during fight-or-flight.’

But why would our brains enter into such a mixed state, representative of neither wakefulness nor sleeping? We need a restful sleep – would it not be more beneficial if the brain went totally ‘comatose’ until that rest was achieved? When one considers our distant, pre-human ancestors, answers begin to take shape. For aeons, the safety provided by the spot where our predecessors chose to lay their heads for the night was, in many ways, compromised compared with the safety of our current bedroom spaces.

Other species employ such strategies as well. I’m reminded of a startling experience I had while hiking. As I was navigating the trail in the twilight, a deer jumped out from underneath the branches of a fallen tree and bolted off into the distance. I was amazed at how close I had come to it before it sprang into furious action – only a few metres. It likely had been asleep and, upon waking, realised the potential danger it was in. What struck me was how the deer seemed to be triggered for action, even while asleep. In fact, many animals can maintain brain activity required for survival during sleep. For example, frigate birds fly for days, even months, and maintain flight during sleep while travelling vast distances over an ocean.

The phenomenon is observed in humans too. On the first night in a new environment, research has shown, one hemisphere of our brain remains more active than the other during sleep – essentially maintaining a ‘vigilant mode’, able to respond to unfamiliar, potentially danger-signalling sounds.

Scientists now agree that bouts of localised wakeful-like activity in motor-related areas and the limbic system can occur without concurrent sleepwalking. In fact, these areas have been shown to have low arousal thresholds for activation. Surprisingly, despite their association with sleepwalking, these low thresholds have been considered an adaptive trait – a boon to survival. Throughout most of our extensive ancestry, this trait may have been selected for its survival value.

‘During sleep, we can have an activation of the motor system, so although you are sleeping and not moving, the motor cortex can be in a wake-like state – ready to go,’ explains Nobili, who led the team that conducted the work. ‘If something really goes wrong and endangers you, you don’t need your frontal lobe’s rationality to escape. You need a motor system that is ready.’ In sleepwalking, however, this adaptive system has gone awry. ‘An external trigger that would normally produce a small arousal triggers a full-blown episode.’

Antonio Zadra, a professor of psychology at the University of Montreal in Canada, explains it like this: ‘Information is being filtered by your brain, which is still monitoring the background – what’s going on around the sleeper – and deciding what’s important. “Ok, so we are not going to wake up the sleeper” or “This is potentially threatening so we should.” But the process of going from sleep to wakefulness is, in sleepwalkers, dysfunctional, clearly.’

Despite evidence of localised activity during sleep in both human and non-human animal brains, sleepwalking is, among primates, apparently a uniquely human phenomenon. It stands to reason, therefore, that the selection pressure for this trait in our ancestors uniquely outweighed the cost.

Philip Jaekl

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.