Transgender brains more closely resemble brains of the sex they align with, rather than what they were born with

Gender studies are leaving the college halls and heading into the lab. Increasingly, there have been more rigorous studies in how transgender people neurologically relate to the sex they identify with rather than their biological sex.

From genetics to brain activity, scientists are delving into the complicated cultural, neurological and biological aspects of sex and gender. Public discourse can be divisive and often ends up muddling the real scientific inquiry into this subject. It’s a widely interdisciplinary field with many different voices contributing to understanding it in a variety of ways. For example, some people like, Siddhartha Mukherjee, physician and author believes that genes are highly influential in determining attributes of gender and sex identity. He states:

“It is now clear that genes are vastly more influential than virtually any other force in shaping sex identity and gender identity—although in limited circumstances a few attributes of gender can be learned through cultural, social, and hormonal reprogramming.”

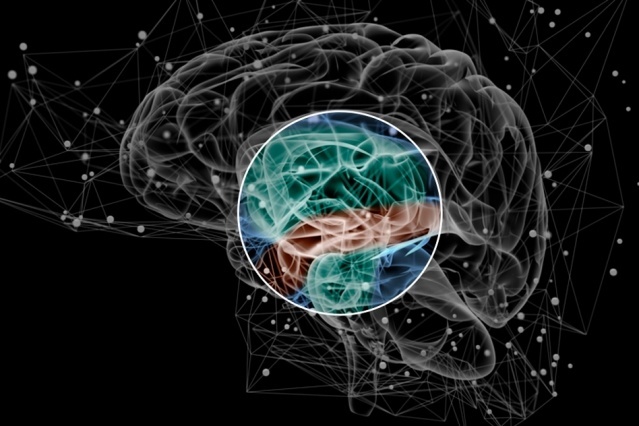

Others believe that they’ve found compelling evidence by studying brain activity in transgender people that closely resembles cisgender people they identify with more than their assigned sex at birth.

A study led by a Belgian University found that brain activity correlated to this neurological hypothesis. Read on to find out more about the study itself.

Members and supporters of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community walk with a rainbow flag during a rally in Kolkata on July 13, 2014. Hundreds of LGBT activists particpated in the rally to demand equal social and human rights for their community and stop social discrimination. AFP PHOTO/ Dibyangshu Sarkar

Latest research out of University of Liege

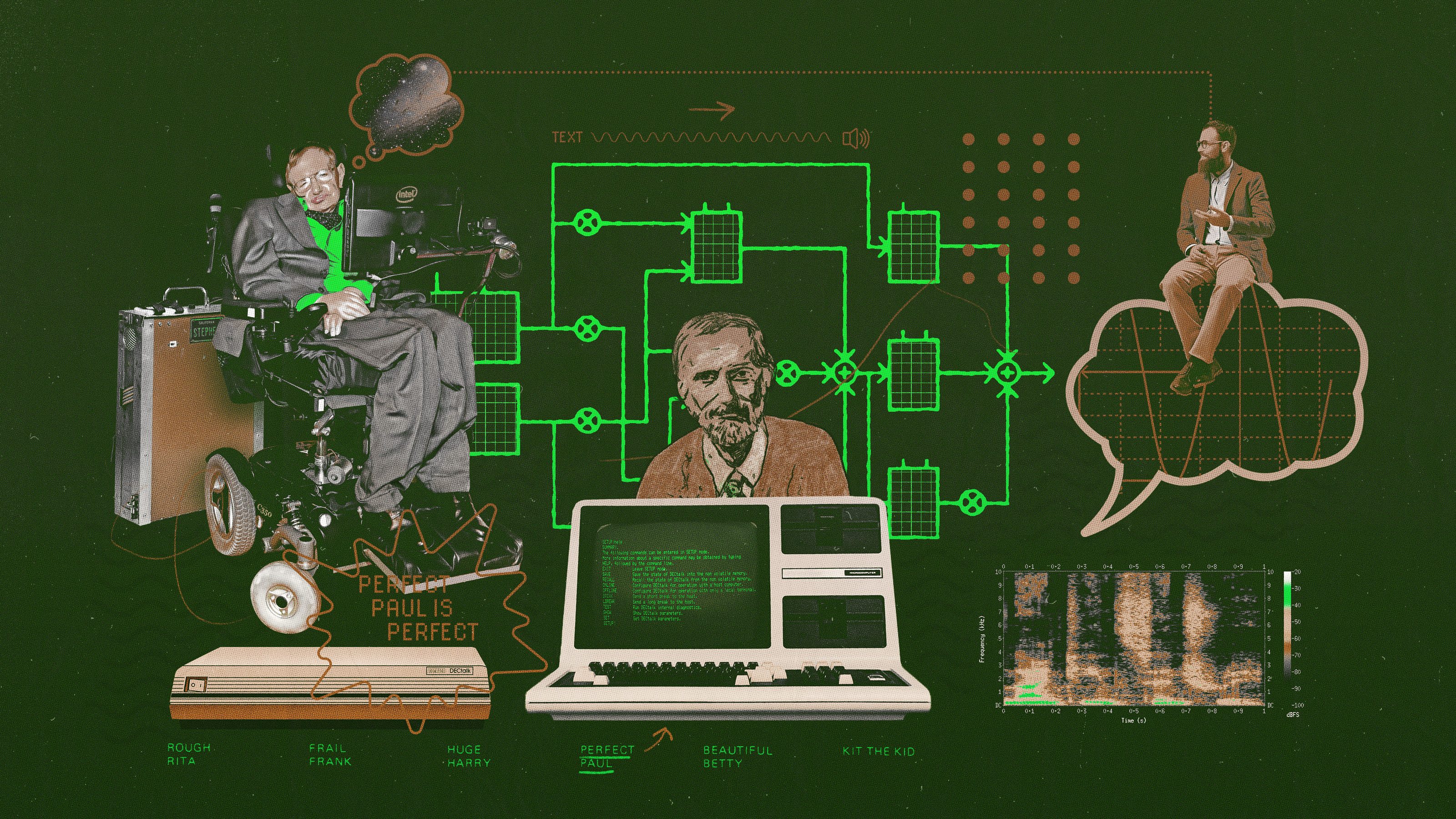

Julie Bakker, who led the research, utilized 160 MRI scans of transgender people diagnosed with gender dysphoria when they were either kids or in their teens. These scans also measured the brain’s microstructures with a technique called diffusion tensor imaging.

After all of these scans were made, they were then compared with people of the same age who had not been diagnosed with gender dysphoria. The study found that transgender boys’ and transgender girls’ brain activity corresponded to both cisgender boys and girls. The MRI tests examined brain activity after an exposure to a steroid and measured gray matter as well.

Bakker believes that this research could be used to help children at an earlier day who’re diagnosed with gender dysmorphia. Bakker stated:

“Although more research is needed, we now have evidence that sexual differentiation of the brain differs in young people with GD, as they show functional brain characteristics that are typical of their desired gender.”

The study’s results aligned with previous studies after it was presented at the European Society of Endocrinology. The analysis further revealed that these neurological differences are detectable at a younger age. Scientists believe that with this new research they’ll be able to offer better advice to young people with GD as this is estimated to affect one percent of the population according to the Gender Identity Development Service.

Former US soldier, whistleblower, transgender Chelsea Manning speaks at the digital media convention ‘re:publica‘ in Berlin, on May 2, 2018. (Photo by Tobias SCHWARZ / AFP)

Further corroboration with other studies

With mounting studies claiming to be able to determine gender through brain scans, many people feel that this would be a great way to help them understand their identity. The neurological activity could be a way of objectively telling what a person defines themselves as from their brain.

In the University of California, San Diego – Laura Case also wanted to test the same idea with an MRI. Laura tested eight trans men (biologically female) against eight cisgender women – who were used as a control group.

Laura found that the trans men had lessened activity in a region of the brain called the supramarginal gyrus. This is an area in the brain which is responsible for giving us a sense of what body parts belong to us. The results may propose that this is less active in transgendered people.

Eventually, more research is planned as gender identity could one day be determined by brain scans alone – if these studies hold up to peer review and scientific scrutiny.