New study suggests we have 6,200 thoughts every day

Image source: The Creative Exchange/Shutterstock/Big Think

- The study passes on figuring out what we think, focusing instead on the frequency of thought.

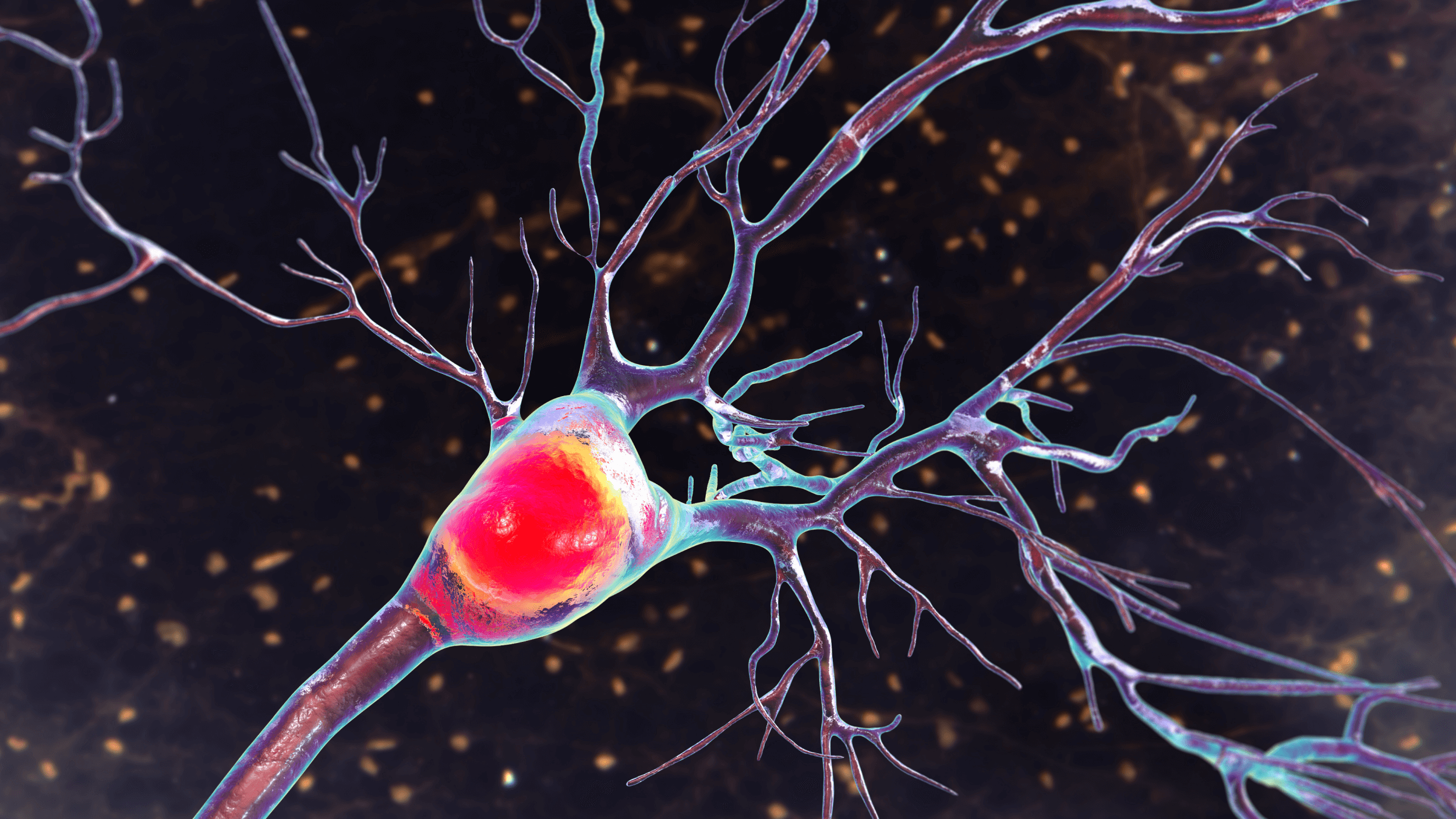

- Consistent neurological signals identify the transitions between thoughts.

- fMRI scans tracked participants’ thoughts while they watched movies and when they were at rest.

A new study from psychologists at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario reports observations of the transition from one thought to another in fMRI brain scans. Though the researchers didn’t detect the content of our thoughts, their method allowed them to count each one. Referred to as “thought worms,” the team says that the average human has 6,200 thoughts per day.

“What we call ‘thought worms’ are adjacent points in a simplified representation of activity patterns in the brain,” said senior study author Jordan Poppenk. “The brain occupies a different point in this ‘state space’ at every moment. When a person moves onto a new thought, they create a new thought worm that we can detect with our methods.”

The study was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

Billion Photos / Shutterstock

Spontaneous thought and attention regions distinguish transitions from meta-stabilityImage source: Poppenk, et al

There’s been a fair amount of research devoted to understanding what a person is thinking based on observations of brain activity. However, the only way to know what a particular pattern of brain activity means would be to recognize its similarity to a brain-activity template known to represent that type of thought. Few such templates are available thus far, and they’re time-consuming and expensive to produce.

Poppenk and his MA student Julie Tseng went another way. “We had our breakthrough by giving up on trying to understand what a person is thinking about, and instead focusing on when they have moved on,” said Poppenk. He adds, “Our methods help us detect when a person is thinking something new, without regard to what the new thought is. You could say that we’ve skipped over vocabulary in an effort to understand the punctuation of the language of the mind.”

A thought, says the study, is generally viewed by researchers as a mental state, a “transient cognitive or emotional state of the organism.” Poppenk says that since such states are relatively stable in terms of brain activity — sustained attention being most closely associated with the angular gyrus — it’s possible to identify transitions between one state and another using fMRI data from individual participants. “We argue that neural meta-state transitions can serve as an implicit biological marker of new thoughts,” the study reads.

The researchers verified their hypothesis using fMRI scans from two groups of participants: some who were watching movies, and others who were in a resting state. “Transitions detected by our methods predict narrative events, are similar across task and rest, and are correlated with activation of regions associated with spontaneous thought.”

“Being able to measure the onset of new thoughts gives us a way,” explains Poppenk, “to peek into the ‘black box’ of the resting mind — to explore the timing and pace of thoughts when a person is just daydreaming about dinner and otherwise keeping to themselves.”

The use of fMRIs is key, he adds. “Thought transitions have been elusive throughout the history of research on thought, which has often relied on volunteers describing their own thoughts, a method that can be notoriously unreliable.”

While we average 6,200 thought worms a day, Poppenk anticipates further research tracking the manner in which the number of daily thoughts an individual has may change over the course of a lifetime. Likewise, he’s interested in investigating potential associations between how quickly a person jumps from one thought to another and other mental and personality traits. “For example,” he says, “how does mentation rate — the rate at which thought transitions occur — relate to a person’s ability to pay attention for a long period?”

In addition, the researcher wonders if “measures of thought dynamics serve a clinical function? For example, our methods could possibly support early detection of disordered thought in schizophrenia, or rapid thought in ADHD or mania.”

“We think the methods offer a lot of potential,” Poppenk says. “We hope to make heavy use of them in our upcoming work.”