Brain hacks for saving money

master1305 via Adobe Stock

- A new episode of “Your Brain on Money” explores how our brains evolved systems that make it difficult for us to sacrifice for the future.

- One major reason that it’s difficult to save is that we tend to view our future selves as strangers with whom we can’t easily connect.

- Saving becomes easier when we learn to connect with our future selves and are mindful of our habits and reward systems.

You find $100 on the sidewalk. How would you spend it? Out of all the options — order pizza, buy new shoes, take your significant other out to dinner — socking it away into your retirement account is probably the least exciting. Saving can feel like you’re throwing money away or giving it to an invisible stranger.

There’s also a decent chance you don’t yet have a retirement account. A survey published in March 2021 found that a quarter of U.S. adults have no retirement savings, while many people who are saving aren’t saving enough. Of course, that’s not necessarily a moral failing. About one in ten U.S. families is living in poverty, and the pandemic brought one of the sharpest ever rises in the national poverty rate.

But even people who can afford to save for the future often don’t. For example, a 2011 study involving salaried employees at seven major companies found that roughly 40 percent of workers failed to invest enough in their 401(k) plans so that their employers would match the contributions, meaning they were foregoing free money.

It is not necessarily wrong to not save a lot of money for the future. But consider the statistics: The median retirement savings account for Americans aged 55 to 64 is estimated to contain about $120,000. If a retiree withdraws money over the next 15 years, that amounts to less than $1,000 per month. That’s under the poverty line.

What about Social Security? Reserves are projected to run out by 2035, at which point beneficiaries will start receiving far less than originally expected. The problems associated with depleted Social Security likely will be compounded by the fact that Americans are generally living longer with each generation.

So, why don’t people save more for their retirement? It’s partly because people often don’t feel like they are saving for their retirement at all.

The disconnect between our present and future selves

In 50 seconds from now, will you be the same person? What about in 50 days? 50 years?

As we project our minds into the future, our conception of ourselves becomes more abstract. Sure, most of us would agree that, in a driver’s license sense, we will still be the “same person” decades from today. But neurological research suggests that is not actually how our brains process this thought experiment.

A large set of brain imaging studies has shown that thinking about ourselves activates a region of the brain called the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). But when we think about other people, the MPFC quiets down and does so even more when we think about others with whom we have little in common.

Studies have observed that the MPFC also quiets when we think about our future selves. In other words, we see our future selves as strangers with whom it is difficult to emotionally connect. A 2011 report on how conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice noted:

“These findings have important implications for intertemporal choice. If people tend to consider the future self as a stranger — that is, if that distant future self feels on an emotional level like another person — then they may rationally have no more reason to save their money for their future selves than to give that money to a stranger.”

The inability to connect with our future selves can contribute to a phenomenon called temporal discounting, in which we care less about future outcomes than immediate ones. A 2008 study explored temporal discounting by asking students to drink a cup of a disgusting liquid for the good of science. Some students signed up to drink it that day, others to do so months later.

The group that agreed to drink the liquid that day chose to drink an average of a couple tablespoons. But the months-later group signed themselves up to down a half cup. Just like procrastinating work or racking up a credit card bill, it is psychologically and emotionally easier to dump today’s problems on our future selves.

The brain in conflict: reward, habit, thinking

Like the self, the brain isn’t a single entity with a singular goal but rather a collection of interacting systems that often conflict with each other. Three broad systems are particularly relevant in terms of planning for the future: reward, habit, and thinking.

These systems evolved over time to serve useful functions. For example, our reward system nudges us to focus on things we need, like food and social connections. Our habits help us perform behaviors — some productive, some not so much — on autopilot, rather than having to deliberate each one. And thinking helps us solve complex problems and plan for the future.

Alex Korb, a neuroscientist, author, and adjunct assistant professor at UCLA, told Big Think that it’s useful to conceptualize these different brain regions as being like different types of friends:

“Your prefrontal cortex, the thinking part of the brain, is saying, ‘Hey let’s do it this way because that’s going to get us to where we’re trying to go.’ And then the habit part of the brain says, ‘Well, no, let’s do it this way because that’s the way we’ve always done it, and that’s more comfortable.’ And the reward center of the brain says, ‘Oh look, there’s a cookie!'”

When it comes to saving for retirement, it’s not a fair fight among these three systems. Our habit and reward systems have the upper hand because they pull us away from long-term planning and toward immediate gratification. After all, it’s relatively easy to keep doing things the way we have always done them, and it is hard to resist immediate rewards.

Interrupting these systems takes willpower. But willpower alone often isn’t enough to do the trick. Some psychologists think that is because we have a limited amount of willpower that can run out after we become too stressed. This idea, called ego depletion, makes sense in terms of saving for retirement, an activity that’s not only financially stressful but also makes us contemplate existential issues like mortality, aging, and purpose.

The depletion of willpower can affect how we perceive rewards. Psychologists Janet Metcalfe and Walter Mischel — Mischel conducted the famous Stanford marshmallow experiment on delaying gratification — proposed that we view rewards with two systems: hot and cool. The American Psychological Association writes:

“The cool system is cognitive in nature. It’s essentially a thinking system, incorporating knowledge about sensations, feelings, actions and goals — reminding yourself, for instance, why you shouldn’t eat the marshmallow. While the cool system is reflective, the hot system is impulsive and emotional. The hot system is responsible for quick, reflexive responses to certain triggers — such as popping the marshmallow into your mouth without thinking of the long-term implications. If this framework were a cartoon, the cool system would be the angel on your shoulder, and the hot system the devil.”

When we choose immediate gratification through the hot system, we not only miss out on long-term rewards but also reinforce our bad habits. So, how can we use the cool system to disrupt our habits and plan for the future?

How to trick your brain into saving for retirement

Odds are that socking away money into a retirement account is never going to feel as exciting as splurging on a night out. But there are ways to make it easier.

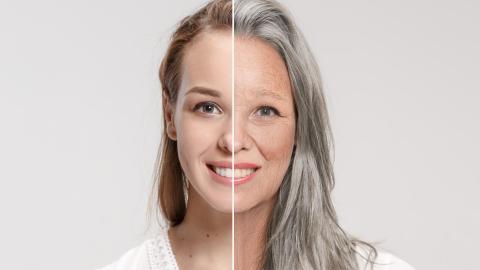

One is to try to emotionally and psychologically connect with your future self. For example, there are applications where you can upload a photo of yourself and see computer-generated images of what you might look like decades down the road. The exercise seems to help people view their relationships with their future selves as less abstract.

A 2011 experiment explored this concept by having two groups of participants view themselves in virtual reality. One group saw a virtual representation of their current selves, while another was shown an age-progressed virtual version of themselves. Afterward, both groups were asked to allocate hypothetical money toward various things, including a retirement account. The group that came face to face with their older selves saved more money.

You do not need virtual reality to start saving. One of the easiest ways is to choose an amount of money to save every month — a reasonable amount that won’t cause too much stress — and then set up automatic deposits into a retirement account. The set-it-and-forget-it strategy utilizes the cool system while removing the “hot system” temptations we face when choosing how to spend a lump sum of money.

Ultimately, it’s not really important how you save, but that you start saving at all. That is partly because compound interest yields higher returns if you start saving early. But it is also because consistently saving money can retrain your brain into thinking saving is important; after all, if you keep procrastinating saving, your brain will learn that it must not be worthwhile.

“One of the keys to being sustainably happy is really just understanding yourself better so that you can make choices that are best for you and your circumstances and understanding your brain can be a big part of that,” Korb told Big Think. “Saving one dollar a day is infinitely better than saving zero dollars per day. So just take one little step in the next direction.”