Inside the mind of a hoarder (and how to help them)

- Roughly 2.5% of the general population has hoarding disorder — the compulsion to keep or collect items, regardless of their value.

- It was commonly thought that hoarding is a type of OCD or depression, but research shows the brains of hoarders behave in unique ways.

- The “Clutter Image Rating” is a great way to encourage hoarders who need help.

The designer, William Morris, had a simple rule: “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Everything else is clutter.

It’s a good principle, and one which many of us would do well to follow. But, there’s a part of our nature that just cannot. When it comes to throwing things away, many of us think, “Oh, I might need that one day,” or, “I can’t throw this away; it reminds me of that great time I had!” In the back recesses of our brain, there lies a tiny hoarder, clutching to vacation souvenirs and pasta rollers like Gollum.

But for some people, that hoarding mindset is not so tiny. It’s so large as to be all consuming and life-altering. Once thought to be a peculiar kind of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), it is now classified as its own condition. (Indeed, hoarding can be a symptom of a few different underlying pathologies.) It is a condition that is subject to TV programs, books, and a lot of research. It’s important to learn as much as we can about hoarding to see the red flags in ourselves, and to help those in our life who need it.

More common than you think

A lot of mental health issues are due to excessive functioning of an otherwise perfectly normal brain function. It’s normal to fear a spider or be nervous about an interview, but generalized anxiety without any (obvious) cause is a problem. We all grieve if we lose someone or feel sad at the end of a relationship, but to feel torpid and disengaged almost constantly is a hallmark of depression. Same goes for hoarding.

Hoarders find it incredibly hard to surrender items. It doesn’t matter how valuable or needed those items are. Hoarding is most commonly seen in people collecting newspapers and magazines, food supplies, boxes, or carrier bags. It might be that we each collect or hoard things in certain measure, but taken to an extreme, it can cause toxic, crippling issues. According to a meta-study of prevalence, it is thought that 2.5% of the general population are hoarders, with both men and women represented equally.

To put that into perspective, around 3.8% of the world suffer with anxiety, 3.7% with depression, 2.8% with ADHD, and 1.4% with alcoholism. All these mental health issues (rightly) get a lot of attention and airtime. But, outside a few slightly voyeuristic reality TV shows, hoarding is not perhaps appreciated in the same way.

The problem with hoarding

The fact is that hoarding is a surprisingly common mental health condition that is as deleterious as any other. Broadly, it affects people in two ways.

First, there’s the psychological aspect. This is where the thought of throwing things away might trigger great distress or anxiety. It is often accompanied by a compulsion to check and recheck that things are still there. Often, hoarding will coexist with self-awareness of the issue, and then a subsequent self-loathing. Hoarders know their habits are abnormal, and yet they cannot help themselves. As one case study about patient “Dee” puts it, “She admitted to ‘crying spells’ and ‘painful emotions’ when thinking about being a failure due to wasted time and inability to control her hoarding problem.”

Second, there’s the physical, practical aspect. People who hoard most likely will have a very constricted, uncomfortable, and disordered living space. There is a clear connection between hoarding and “squalor” — where a home is so “unclean, messy, and unhygienic that people of a similar culture and background would consider extensive clearing and cleaning essential.” Hoarders are often socially reclusive, withdrawing from friends, family, and society more broadly. This might be due to some accompanying depression, but might also stem from the self-loathing mentioned above. Hoarders are often ashamed of their homes and their condition. They recognize that the clutter and mess is something few others want to see.

The mind of a hoarder

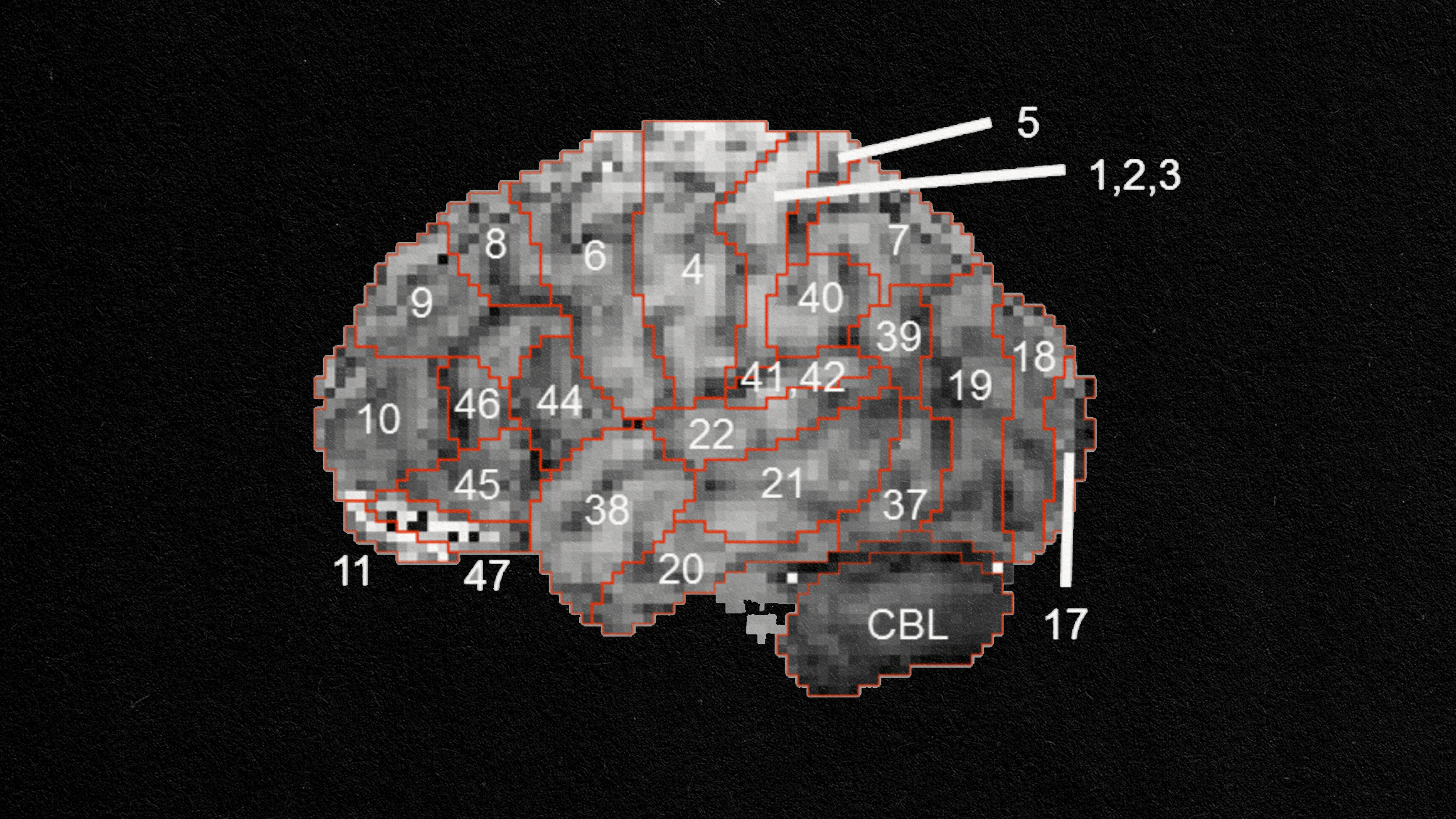

It was long thought that hoarding “belong[ed] to the class of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders.” And it’s certainly true that hoarding often comes attached to a host of other mental illnesses. But one study, run by Dr. David Tolin of Hartford Hospital and Yale University, went to show how “differences in neural function correlated significantly with hoarding… were unattributable to OCD or depressive symptoms.” In other words, the brains of hoarders and the obsessive or depressed are different.

But what, exactly, is different about a hoarder? What Tolin discovered is that a hoarder has abnormal activation in the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of the brain, areas that regulate emotional responses to objects. The insula and ACC tell us whether an object is important to us or not. It differentiates your dog from “a” dog. It’s the feeling of pulling up to your house. It’s the feeling of drinking from your coffee mug. When we see objects that matter to us, we can thank the insula and ACC.

Hoarder brains, however, have two abnormalities. First, they have really low activation when looking at others’ possessions or objects — much below that of control subjects. Second, they have activation overload when looking at their own possessions. In short, their brain cares far too much about things it labels “mine.”

How to help a hoarder

If you notice any of the signs of hoarding in your loved ones — or, perhaps, yourself — then you likely will want to help in some way. Here’s what the experts tell us:

Be kind and gentle. Few mental illnesses, if any, are best treated by judgments or heavy-handedness. Mental illnesses almost always come accompanied by complicated feelings of shame, embarrassment, and denial.

Make them safe. If their home is unfit for habitation — with perilous stacks of items, fire hazards, or seriously unhygienic locations — then it is best to call a professional for help. Saving someone’s actual life and welfare ought always come first.

Support them in getting help. One of the best tools to persuade someone to get help is known as the “Clutter Image Rating.” Show them the various pictures, and if they score higher than #4, gently suggest that clinicians recommend that it’s time to get help.

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.