How psychopathy might be an evolutionary adaptation

- It might seem obvious that psychopathy is harmful. But there is some reason to believe psychopathy, at least in moderation, might be a reasonable evolutionary adaptation.

- To evaluate whether something is a mental disorder, it helps to understand what causes disorders in the first place.

- A recent study explored whether psychopathy is associated with physical telltale signs such as handedness. The results were not conclusive, but they do add to a growing body of research supporting the possibility that psychopathy is not a mental disorder.

Dan is a psychopath. But he is smart, charming, and successful. You would not know from first meeting him that he feels pride rather than remorse when he regularly plays the system, deceives people, and exploits others to get what he wants.

But does Dan have a psychological disorder?

Lesleigh Pullman and colleagues recently set out to assess the hypothesis that psychopathy might not be a mental disorder, but rather an effective life strategy. To do so, they analyzed a surprising sign of mental disorders: handedness.

Defining psychopathy and mental disorders

Psychopathy is characterized by emotional and interpersonal deficits such as callousness, grandiosity, and a lack of empathy and remorse. It sometimes involves deviant behavior like aggression and violence. Diagnosis is generally based on interviews or self-reported questionnaires that assess selfishness, remorseless use of others, and lifestyle.

Though the term is often used for run-of-the-mill jerks, less than 5 percent of the population — maybe even less than 1 percent — is selfish and remorseless enough to qualify as a psychopath.

Pullman and her colleagues take an evolutionary perspective on what constitutes a mental disorder, specifying that it must be a harmful dysfunction. To add up to a mental disorder, in other words, behavior cannot just fall outside of the norm. Instead, the behavior must constitute a failure to perform a function that evolution selected because it helps a person.

In other words, psychopathy must harm a person’s functioning or wellbeing if we are to consider it a disorder.

It might seem obvious that psychopathy is in fact harmful. Psychopaths struggle to maintain relationships. They are more likely to die prematurely and to be incarcerated. Hart and Hare, for example, argue that given its negative impact on society, psychopathy is perhaps second only to schizophrenia as a public health concern.

Moreover, psychopathic traits are integrated into the criteria for disorders formally recognized by the American Psychological Association and the World Health Organization. Though Antisocial Personality Disorder and Dissocial Personality Disorder more heavily influence observable antisocial behaviors such as lawbreaking and violence, both personality disorders incorporate lack of empathy, lack of guilt, and deceitfulness.

Why psychopathy might be an adaptive life strategy

Still, there is some reason to believe psychopathy, at least in moderation, might be a reasonable evolutionary adaptation.

Imagine for instance that it is 6,000 BCE. You live in a tribe where most people are honest and considerate, but there is not enough food for everyone. In such a case, if you are willing to cheat your trusting tribemates out of some of their food, you are more likely to survive and pass along your swindling genes to children.

Even today, psychopathic traits might be common and helpful in competitive settings like Wall Street, especially when the psychopath is able to keep any violent or criminal behavior under wraps.

What causes disorders?

To evaluate whether something is a mental disorder, it helps to understand what causes disorders in the first place.

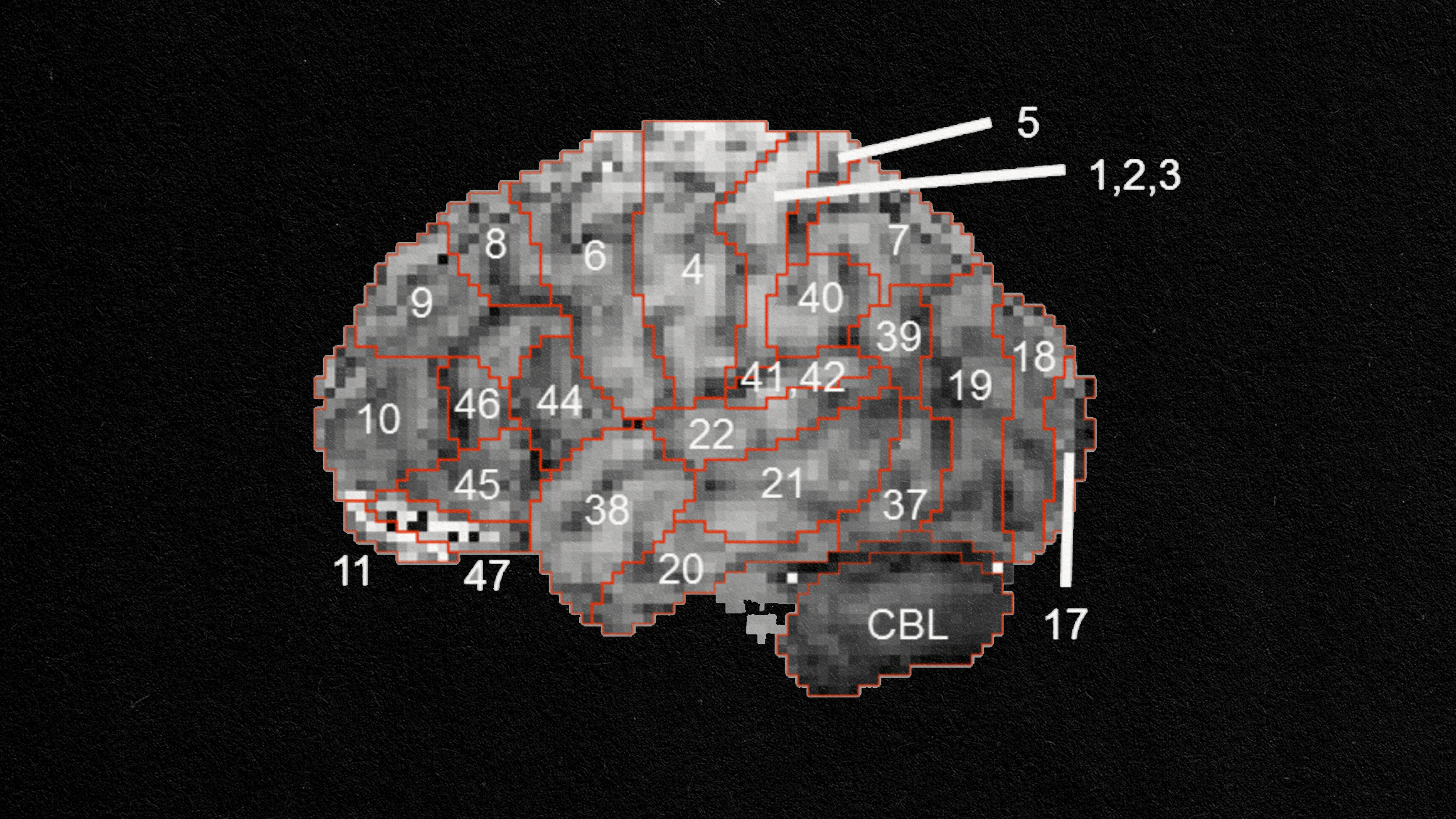

Scientists are still uncovering the various causes, but one likely influence is neurodevelopmental perturbations — that is, anything that upsets the normal course of brain development. Perturbations can occur for numerous reasons before or after birth. Causes include maternal infection or stress while pregnant, childhood malnutrition, head injury, and emotional trauma. Neurodevelopmental perturbations are linked to various mental disorders including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism, and schizophrenia.

Directly assessing neurodevelopmental perturbations is difficult. It generally involves scanning brains with special equipment or collecting in-depth data about a person’s childhood, maternal wellbeing, and so forth.

But one marker of neurodevelopmental perturbations is handedness.

Sorry lefties, but left-handedness and ambidexterity — in short, non-right-handedness — are associated with maternal stress during pregnancy, birth complications, and low birthweight. Compared to their right-handed counterparts, non-right-handed people are also more likely to have mental illnesses ranging from depression to schizophrenia.

And these differences are not small. For example, around 11 percent of the population is left-handed, but estimates suggest that around 40 percent of people with psychotic disorders are left-handed. (On a positive note, lefties might be more creative!)

Left-handedness and ambidexterity may be linked to mental disorders because they result from the brain’s failure to effectively lateralize during development. Brain lateralization confers many benefits, including avoiding duplication and allowing for the specialization of different brain areas.

Finally, the study

To test their hypothesis that psychopathy is an adaptation rather than a mental disorder, Pullman and her team combined data from 16 prior studies. The studies involved 1,818 people from various populations. They measured handedness and psychopathy, and calculated whether psychopaths were more likely to be left-handed or ambidextrous than their kinder counterparts.

In short, psychopathy was not reliably related to handedness. Tiny differences did show up, but they gave no reliable answer.

When looking at typical people from throughout the community, as well as incarcerated inmates, those who scored high on psychopathy were slightly more likely to be non-right-handed. When looking at mental health patients, however, psychopathic offenders were slightly less likely to be left-handed than their non-psychopathic counterparts. All of these differences were so small and unreliable as to be likely due to chance.

Interpret with care

The meta-analysis of more than 1,800 people failed to link psychopathy with handedness. This supports the hypothesis that psychopathy is an adaptive life strategy passed down through genes thanks to evolution, and not a mental disorder resulting from neurodevelopmental perturbations.

Taken alone, however, these findings are not especially convincing, for a few reasons. First, the data did show some patterns suggesting that people higher in psychopathy may be more likely to be non-right-handed. But, the sample size may have been too small to detect real differences.

Moreover, psychopaths had about the same rates of non-right-handedness as incarcerated inmates and mental health patients. But if psychopathy is never a mental disorder, we would expect psychopaths to have lower rates of non-right-handedness than these groups (since these groups probably have more mental health disorders, and thus higher rates of non-right-handedness, than the general population).

Taking the broad view

Another interesting possibility is that psychopathy is helpful, but only when people can keep violent and criminal behavior under control. This is supported by Pullman and team’s finding that people high in the traits of psychopathy (for instance, callousness or lack of remorse) were slightly less likely to be left-handed or ambidextrous, whereas those high in behavioral psychopathy — such as committing violent or criminal acts — were more likely to be non-right-handed. Though these results were not statistically significant, the conclusion seems reasonable.

Though this single study does not convince me that psychopathy is necessarily an adaptive, evolution-based life strategy, it does add to a growing body of research supporting that possibility.

For example, it is consistent with data showing that people high in psychopathy are likely to commit calculated, goal-directed crimes rather than emotional ones; prioritize their own wellbeing as well as the wellbeing of their offspring; and tend to have more children.

So, while the jury is still out, know that psychopaths like Dan might not have a mental disorder at all. They might just be self-serving jerks.