5 ways Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. changed American history

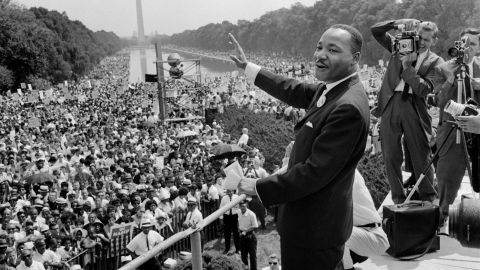

It was 50 years ago on April 4th, 1968 that millions across the United States and the world were stunned to learn that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Prior to that, for many people, the simple knowledge that Dr. King was out there somewhere working to make the world a better, fairer place had been a comfort, and his killing came as a gut-wrenching shock. People who followed the activist preacher more closely — and certainly King himself — were less surprised. In 1966, after all, a bomb had exploded on the porch of the King residence and death threats were a daily occurrence for his family; he was also surveilled with suspicion by the U.S. government. The night before he died, King spoke to a crowd in Memphis:

Well, I don’t know what will happen now; we’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter to with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

Dr. King’s signature insights

Some of King’s signature insights:

- Those in power can be expected to divide people against each other and use those divisions to provoke violence. However, strategic protest can neutralize those outcomes.

- Media, especially television, is a powerful platform that can be leveraged to reach the heart of the American public.

The tactics of power that King wanted to defeat

The nasty game of us vs. them

The idea here is to pick a characteristic held by some people within the population and promote those people as somehow different and responsible for everyone else’s hardships. It may be skin color, it may be religion, but whoever the target is, the intention is to create a decoy enemy: they want our money, they want our possessions, they’re taking over, they’re denying us what’s rightfully ours.

It’s a devastatingly effective trick because it distracts from the true problem, presenting a make-believe zero-sum game where either you win or they do. In reality, however, what is being fought over is merely what remains after the powerful have satiated themselves.

The trick is especially insidious because people lower and lower in the power structure — having taken the bait — are more willingly join in. At that point, us vs. them rationalizes cruelty toward others as the freedom to protect one’s domain.

Us vs. them is not just an illusion for the masses — it serves equally well as a self-delusion for the powerful. Consider slaveholders who chose to view their slaves somehow different, somehow less, and unworthy of consideration or fair treatment.

Provocation of violence as an excuse for repression

When people do speak up, particularly as a group, the powerful have the option of silencing them using armed police, military personnel, and so on. However, to preserve the illusion that the problem is with the fictional them, authorities may deliberately provoke — or even invent — a violent act on the part of people raising their voice to justify the deployment of brutal force. It’s a trick that’s been employed when workers went on strike, and we still see it today when agitators, some of whom are planted by opponents of the cause being promoted, appear at gatherings and attempt to provoke violence.

Dr. King’s legacy

King’s struggle sadly continues in 2018. There have been steps both forward and back across the racial divide he sought for years to bridge. Late in life, King focused on the problem of economic inequality, which has gotten worse since his death.

We’re still easily divided against each other by fear, and inexcusable violence is excused by those in power on a regular basis. Still, there’s reason to hope: Progress eventually tends to move forward. Nonetheless, King’s lasting impact is indelible and multifaceted, his life a model of commitment and his strategy a continuing influence on those still struggling for positive change in America and throughout the world. Across the globe over a thousand streets have been renamed in tribute. Here are five examples of his lasting impact.

1. Dr. King was the first to master TV as a force for change

America watched the charismatic, captivating King as he spoke, marched and was attacked and arrested. Through him, the entire nation began, at last, to see just how false the us vs. them narrative really was. Racial discrimination was no longer something that only its victims had to reckon with, but a grave problem for the American soul. Designed to be viewed from the average Joe’s couch, King devised political spectacle that would inevitably attract TV coverage that just as inevitably changed the heart of a nation.

King’s gatherings provided a model that still works. Even in 2018, the sight of crowds gathering for an idea remains powerful in demonstrations such as 2017’s Women’s March and the March for Our Lives rallies this year in the wake of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting.

2. America began to confront its post-slavery race problem

King would no doubt be the first to remind us that he traveled with many others on the road towards the end of legal segregation in the United States and the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1964. Still, it would be difficult to overstate the magnitude of his personal oratory and influence, and the fundamental way that it changed America’s understanding of both its racial history and its current culture.

3. Showing America to itself

Most people know by now that there’s no such thing as race, biologically — it’s simply an arbitrary social construct. By so eloquently invoking our moral obligations to each other, King made it clear that we’re all in this together, and as a result, a gathering of his supporters was a tapestry of people in all shades, sizes, ages, and genders.

To watch a rally on TV such as in 1963’s March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs was to see a new, vital United States. Not the white one depicted on our other shows or in history books taught from in schools. It was the first good look Americans got at themselves.

4. The power of non-violence demonstrated

King advocated non-violence categorically and weathered his critics who said that violence was the only way to truly get oppressors’ attention.

Non-violence allowed King to keep attention focused on the issues at hand while allowing people of good conscience to participate (and feel safer doing so). On a more strategic level, though, he was well aware that non-violence may be returned with violence, resulting in TV coverage that would help the viewing public to sympathize with his cause and pierce any indifference to racial issues

5. Poverty is not just a problem of theirs. It’s everyone’s problem.

Towards the end of his life, King had refocused his efforts on the pernicious and devastating effects of poverty, regardless of its victims’ complexions. He saw inequality growing, and as a crucial danger to the entire nation. In 1968 when he died, 12.8% lived below the poverty line. The number in 2016 was 14%.

To listen to some, welfare in the U.S. today primarily benefits black Americans and immigrants. It’s not true: Poor whites receive the lion’s share of government money. Of the 70 million Medicare beneficiaries in 2016, 43% were white, 18% black, and 30% Hispanic. 36% of the 43 million food stamp recipients that year were white, 25.6% black, and 17.2% Hispanic (the remaining recipients are unknown).

Difficult days ahead

We are still far from King’s promised land. Yet no matter how heartbreaking the setbacks are, forward is the only direction we can go. Race is not even a consideration in contemporary music, TV, and films. We just need to keep calm — as King preached — and take care of each other as we travel forward together. In the long run, there’s simply no other sensible choice. We may yet arrive.