Saying “No” to Censorship: The Fight For a Free Internet is In Our Hands

What’s the Big Idea?

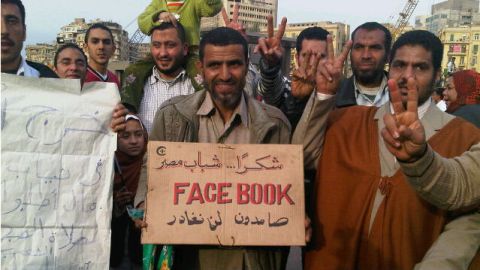

On May 20, Pakistan shut down Twitter for eight hours after the microblogging site refused to remove tweets that linked to a page encouraging people to post pictures of Muhammad. The move backfired: rather than diverting eyes from the offensive content, the government turned it into a news story. As Farieha Aziz of the Bolo Bhi advocacy group told the Guardian: “Shutting down Twitter will just drive more traffic to them.” (Approximately 360 million people around the world hold Twitter accounts, and tech-savvy users know how to circumvent outages.)

The same week, New York lawmakers introduced a bill that seeks to decrease cyberbullying by banning anonymous posting on the web. If passed, the bill would require site administrators to delete any comments without a name, contact information, and IP address tied to them. PC Magcalled the proposed legislation “so stupid it hurts.”

In both cases, governments approached social media as if it was a threat to be controlled, and in both cases, their response was attacked as clumsy, futile, even embarrassing. The lesson? Technology policy and containment strategy don’t mix. Attempts to influence the way information is shared online rarely achieve their desired effect, and they also convey (sometimes intentionally, sometimes not) a general sense that communication is dangerous in the digital age. Inevitably, the question becomes, dangerous to who?

The internet gives an unprecedented level of power to people at the edges, says Rebecca MacKinnon, a Bernard Schwartz Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation who conducts research on global Internet policy, free expression, and the impact of digital technologies on human rights. “Internet platforms and services… along with a range of mobile, networking and telecommunications services, have empowered citizens to challenge government, both our own as well as other governments whose actions affects us.”

They also provide activists with effective tools for outreach and promotion at little or no cost, making grassroots organizing feasible for people who would otherwise not have access to more traditional avenues of political expression. Once again, technological advances have paved the way for a revolution in global governance. “People are using the internet to protest against what they see as injustice. That’s something that we definitely want to encourage,” says MacKinnon.

What’s the Significance?

But the Internet is only as free and open as we make it. Technology also has the potential to be used by oppressive governments to undermine human rights and censor speech. “What we need to make sure is that when censorship is happening on the internet that people know about it — when surveillance is happening on the internet, people know who’s doing it and they can hold the people who are censoring and surveilling accountable.”

That means transforming our collective role from passive user of the net to active digital citizen. It means taking ownership over our virtual spaces, and advocating for our values in cyberspace as we do in our physical space. (Check out MacKinnon’s specific words of advice for individuals here.) It also means thinking beyond nation-states, as online platforms increasingly connect people with the same needs and interests across borders.

One place to start is Global Voices, which MacKinnon co-founded with Ethan Zuckerman while at the Berkman Center For Internet & Society. The site is an international community for citizen journalists and translators which emphasizes and promotes voices that are not ordinarily heard in mainstream media. Posts are available in 25 languages, including Turkish, Polish, Spanish, Italian, Swahili, Portuguese, Filipino, Russian, and Malagasy, the national language of Madagascar.

Last week, a New Yorker could have turned to Global Voices to read about Pakistan’s Twitter-less weekend from a dentist in Karachi who’s been blogging about Southeast Asian politics since 2004. Or an analysis of the Occupy Wall Street by a native of Bogotá, Columbia who has also contributed to el Sun Sentinel, The Miami Herald, United Nations Chronicle, and the Center for American Progress. Someone based in Hong Kong could have read about the escape of blind civic rights activist Chen Guangcheng from Beijing.

As MacKinnon says, the very reason for the existence of the internet is collaboration — removing barriers to global communication, not erecting them. Why else put so much time and effort into perfecting search algorithms and SEO optimization? The point of the internet is finding each other.

This past month, Big Think has been running a series called Humanizing Technology, which asks the broad question of how technology can empower us, not make us more vulnerable. To view other examples of new and emerging technology that accomplishes this, visit the series here.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.com