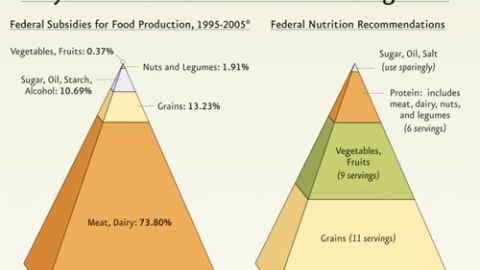

How We Subsidize Obesity

Bloggers are talking today about a striking chart comparing the foods we should be eating with the foods the government subsidizes. The chart, originally published in 2007 by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), shows two side-by-side food pyramids. On the right is a version of the standard food pyramid, showing federal nutrition recommendations—that we should have 11 servings of grain a day, 9 servings of fruits and vegetables, 6 servings of high protein foods like meat and dairy products, and small amounts of things like sugar, oil, and salt. On the left is a pyramid showing the extent to which we subsidize each of those food groups.

Meat and dairy products got almost 3/4 of federal food subsidy money between 1995 and 2005, in spite of the fact that they should make up less than 1/4 of our diet. Sugar, oil, and other things we shouldn’t eat very much of got around 10% of the federal money. And fruits and vegetables—which should be about 1/3 of our diet—received essentially no federal aid at all.

The Consumerist posted the chart with caption: “This is why you’re fat.” Americans are, of course, fat. With one in three Americans clinically obese, we are one of the fattest countries in the world. Why exactly that is is a complicated question. But part of the reason is that we eat too much of the wrong foods. While we may not need any extra incentive to eat sweet or fatty foods, we would probably eat less of them if they weren’t so cheap. In fact, we can often buy unhealthy foods for less than they actually cost to make, because we use so much tax money to subsidize their production. Healthy foods, meanwhile, still cost full price.

Why are we subsidizing foods that we eat too much of? The main reason, of course, is that producing them is a huge, profitable, and politically well-connected industry. Derek Thompson isn’t far wrong when he writes that “The federal government’s food subsidy policy exists to manage supply and protect prices for farmers with excellent lobbying groups.” Not only do we spend billions of dollars subsidizing the corn and soy to be fed to livestock, but we also buy enormous quantities of surplus—and often unhealthy—food for food assistance programs, including school lunches. Partly as a result, the prices of less healthy foods have been falling, while the prices of more healthy ones have gone up. Catherine Rampell links to another chart David Leonhardt put together last year, showing how starkly the prices of healthy and unhealthy foods have diverged. Over the last 30 years the relative price of meat and butter fell dramatically. The relative price of soda fell by 33%. But the relative prices of fruits and vegetable climbed dramatically—by more than 40%—over the same period. That’s why a salad costs more than a Big Mac.

A number of cities—like New York and Philadelphia—are considering taxing soda, both to encourage people to drink less and to fund programs to treat the health problems associated with obesity. Whatever its merits, however, the idea of taxing something like soda to discourage people from drinking it smacks of paternalism. Why should the government dictate to us what we should eat or drink? But the fact is, as Derek Thompson says, that we already have a tax policy that radically distorts the price of what we eat. Except the point of this policy isn’t to make us healthier, but to pad corporate profits.