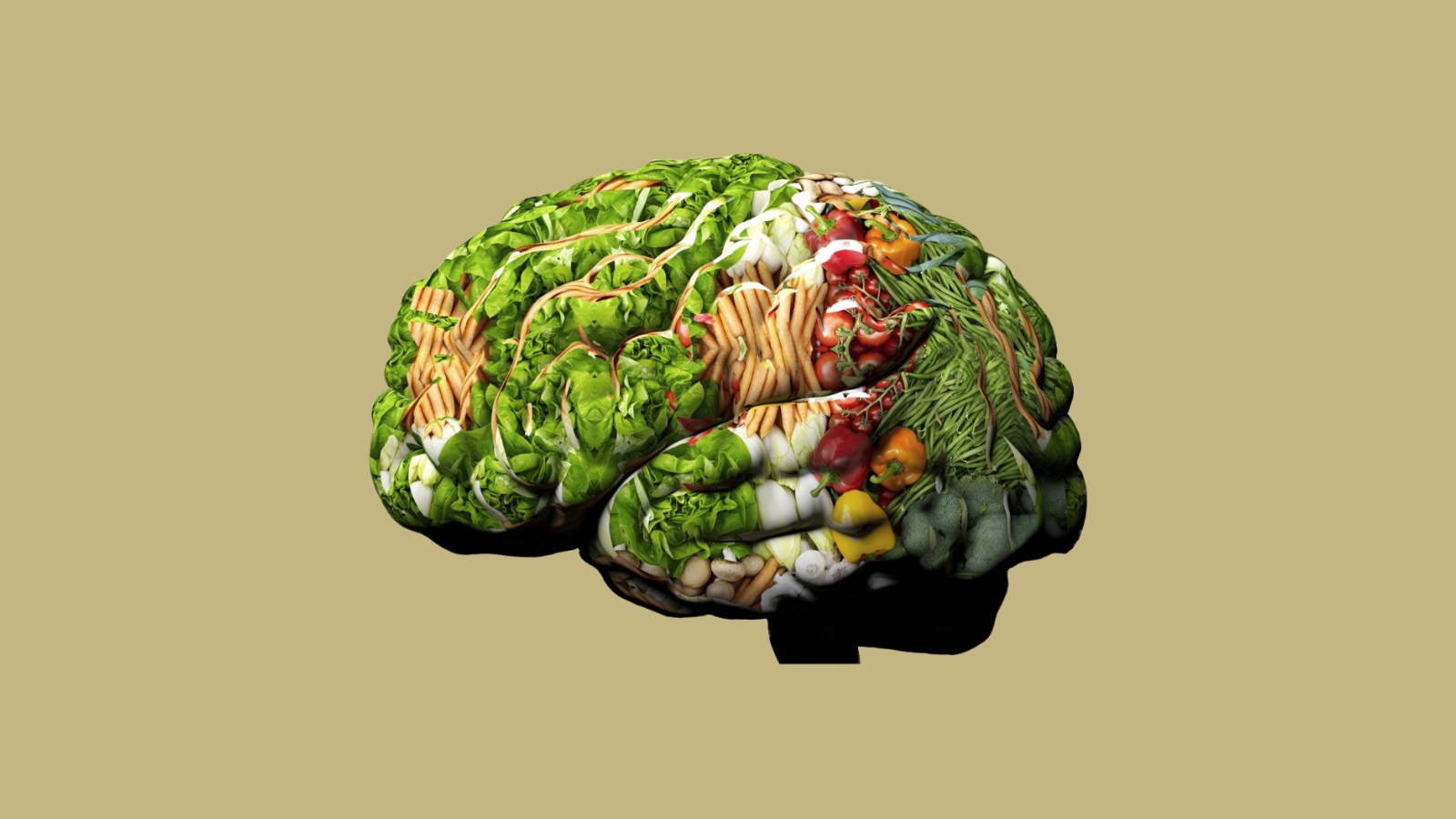

Should ‘ultra-processed’ foods include health warnings?

PxHere

- A growing body of research, including two recent studies, shows how ultra-processed foods can lead to multiple diseases and shorten lifespan.

- Ultra-processed foods include soft drinks, packaged snacks, reconstituted meat, pre-prepared frozen meals, and more.

- Other research suggests that warning labels on food can affect what people choose to eat.

The U.S. government requires sellers of cigarettes and alcohol to include health warnings on the labels of their products. Should vendors of “ultra-processed foods” be required to do the same? New research has some saying yes.

This week, the BMJ published a pair of studies that show how diets high in ultra-processed foods are linked to significantly higher rates of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and death. The findings build upon decades worth of evidence showing that processed foods can be devastating to long-term health.

In the four groups that make up the NOVA food classification system, ultra-processed foods are ranked as the unhealthiest. They include “soft drinks, packaged snacks, reconstituted meat, pre-prepared frozen meals,” with ingredients like “sweeteners, colors, preservatives, and food-derived substances like casein, lactose and gluten.”

These foods are unhealthy not only because they contain bad ingredients or lack nutrients, but also because they undergo processes like extrusion, molding, and milling.

“The nature of the cause is associated with the physical and chemical changes that happen to the food as a result of this high degree of industrial processing,” Mark Lawrence, who co-wrote an editorial on the pair of recent studies, told Australia’s ABC News. “It’s an independent risk factor irrespective of the presence of, say, sodium or added sugar in the food.”

Lawrence said the recent studies, along with the solid body of research on ultra-processed foods, have multiple implications for policy.

“I think the front of pack labelling is the most tangible one at the moment,” Lawrence said. “It could be something as simple as, is this an ultra-processed food or not.”

Junk food warnings

Would requiring makers of ultra-processed junk foods to include such labels on food be government overreach? Provided that you’re okay with the warnings the U.S. government currently puts on tobacco and alcohol, there seems to be little reason why we shouldn’t place the same labels on ultra-processed food. In fact, there may even be more reason to include warnings on junk food, as noted by David Katz for Time:

“. . . unlike tobacco or alcohol, food is supposed to be good for us. It is supposed to be sustenance, not sabotage. You can’t smoke tobacco and avoid tobacco. You can’t drink alcohol and avoid alcohol. But you can eat food and avoid junk. There is, in fact, an impressive range of overall nutritional quality in almost every food category — so we could abandon junk food altogether, and quickly learn not to miss it.”

There’s some reason to think junk-food warning labels would be effective in affecting what people choose to eat. In a 2018 study from the University of Melbourne, researchers found that warning labels — particularly graphic, negative warnings — encouraged people to exercise self-control when selecting meals.

“We can really see a signature of deploying this self-control to resist unhealthy choices,” study co-author Stefan Bode of the University of Melbourne told Australia’s ABC News. “This is something we’re really excited about to follow up and see how this happens.”