Scientists Find That the Body’s Bacteria Can Communicate Electrically

We have a two-sided relationship with bacteria. On one hand, these single-celled organisms are the source of disease. On the other, each of us hosts some 40 trillion bacteria in our own personal biomes — some estimates suggest we’re 90% bacteria, 10% human. However many there are, these fellow travelers help us break down our food, affect our emotions, and play a part in our lives that we’re just beginning to comprehend. In fact they’re so important in both roles — just last month, a woman died from a bacterial infection that overcame all of the available antibiotics — we can hardly know enough about them. And now a new study published in Cell says they can communicate with other electrically at a distance.

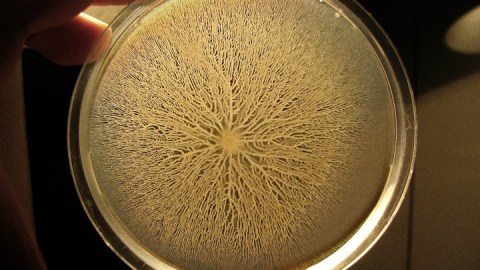

Scientists at University of California, San Diego were interested in the behavior of bacteria in biofilms. A biofilm is a bacterial community, a thin, slimy layer where bacteria have attached themselves onto something.

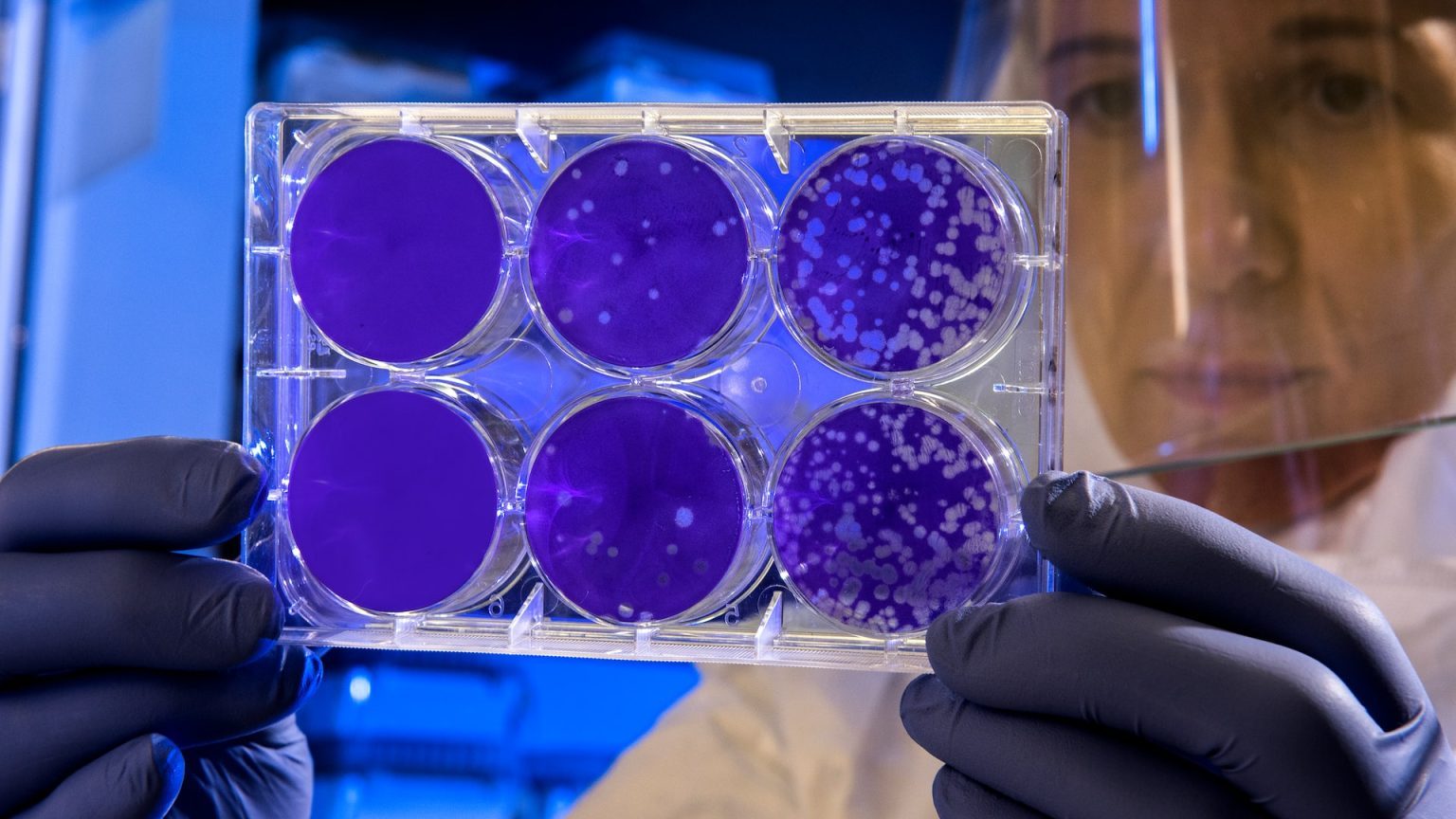

Biofilm from previous study (SÜEL LAB)

Biofilms can be found in lots of places, including, for example, plaque on your teeth. Biofilms are believed to be responsible for 80% of all microbial infections, and they’re tricky to treat, since each one can contain multiple bacterial strains: There’s no guarantee that an antibiotic that addresses one will address them all.

Previous research had demonstrated that bacteria could pass information back and forth, much the way neurons do, through small pores, ion channels, that pass electrically charged potassium molecules between them. This allows potassium-hungry bacterial cells on the inside of a biofilm to signal outer cells to stop scarfing up all of the available nutrient.

What’s amazing about the new research is that apparently bacteria in a biofilm can call out to other bacteria elsewhere in a body, sending a sort of eVite to come join and strengthen the community.

What happens is that the potassium ions don’t stop at the biofilm’s edge — they continue to spread outward. The team at UC San Diego combined lab experimentation using microfluidic growth chambers and tracking dyes along with computer modeling. The researchers found that a species of Bacillus subtilis bacteria was able to recruit Pseudomonas aeruginosa through electric signaling.

(SÜEL LAB)

It looks like potassium ions are common currency for all types of cells. Study team member Jacqueline Humphries told The Atlantic, “It allows species to communicate across evolutionary divides and create mixed communities.”

There may be a much more complex interaction between the various kinds of bacteria in the biome than was previously recognized since, as lead researcher Gürol Süel told the UC San Diego News Center, “bacteria within biofilms can exert long-range and dynamic control over the behavior of distant cells that are not part of their communities.”

This is a big change to the way in which scientists view these not-so-simple-after-all creatures. In terms of medical treatment, for example, the new understanding of how biofilms — like staph infections — come together could lead to figuring out how to break them apart.

Süel continues, “Our latest discovery suggests that the composition of mixed-species bacterial communities, such as our gut microbiome, could be regulated through electrical signaling. It may even be possible that bacterial and human gut cells can interact electrically within the human gut. Our work may in the future even lead to new electrical-based biomedical approaches to control bacterial behavior and communities.”