Draining the Swamp Chicago Style, Milton Friedman and When Government Is the Problem.

The Trump administration has officially taken shape. Among the cabinet positions is Rick Perry as the Secretary of Energy. A position which he previously promised to eliminate if elected president. In a similar vein, Betsy DeVos is managing the Department of Education, a department which Trump has expressed interest in abolishing.

While the populist opposition to these departments is well known, one might ask if there is any intellectual backing to the idea of dramatically cutting down the size and scope of the Federal Government, especially these two important departments.

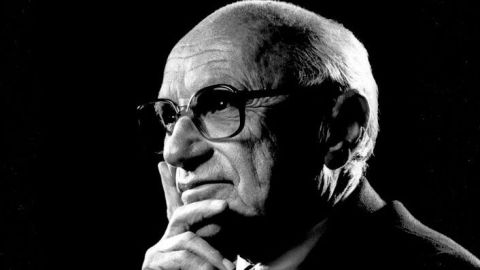

There is, and some of it comes from the mind of the Nobel Prize Laureate economist Milton Friedman. Friedman was a Chicago School economist, who supported a series of libertarian policies ranging from an all volunteer military, to school choice, to a form of the guaranteed basic income.

Friedman thought that a myriad of social problems can be blamed on the management of the issue by the government.His objection was not to the use of the state per se, though he remained a committed libertarian, it was rather to the influence of special interests who were able to use non-democratic systems to exert undue power and keep the system working for them rather than the many.

To quote him directly:

“I believe our present predicament exists because we have gradually developed governmental institutions in which the people effectively have no voice.”

He uses the example of the number of taxi cabs in New York City in the early nineties to illustrate his point:

“I have long been interested in the problem of regulation of taxicabs, so I asked (about) the market price of a medallion to drive a taxicab. As you know, the number of taxicabs is limited by government fiat. The medallion signifying permission to operate a taxicab is transferable and traded in a relatively free market. Its current price is apparently now somewhere between $100,000 and $125,000. If the limitation on the number of taxis were removed, the benefits would greatly exceed the losses. Consumers would benefit by having a wider range of alternatives. The number of cabs would go up and so would the demand for drivers. To attract more drivers, the earnings of drivers would have to rise. In economic jargon, the supply curve of drivers is positively sloped. Why does the limitation of the number of cabs persist? The answer is obvious: the people who now own those medallions would lose and they know it. Although they are few, they would make a lot of noise at city hall.”

The Harbingers of Oligarchy?

To Friedman, even decent government goals, such as the enforcement of law, can suffer from this problem of runaway interests. Until, eventually, the situation becomes rather dissatisfying for the average individual. He does suggest two solutions. The first is to remove government from places where he thinks it doesn’t belong; such as education, housing, healthcare licensing, and banking. Therefore allowing it to do what it should do to our satisfaction.

But secondly, he felt strongly that our system had morphed into one where most officials that were doing a poor job, or had a vested interest in not being subject to performance review, were truly in control with their oversized influence; as seen above in the taxi cab example. He suggested several solutions to this too, such as term limits for congress, and a review of the merits of the spoils system.

Trump’s plan to eliminate the Department of Education fits well into Milton Friedman’s notion of “government is the problem”. By abolishing the Department of Education, Friedman would argue that local communities, which are in theory more democratic, could exert control over their money and education systems. Perhaps even instituting more school choice, which he saw as the key to improving education. If this is true or not is another issue.

Milton Friedman was a Chicago school economist who thought that government was the problem in most cases. While his policies were radical, his principles were often not. His concern for the power of special interests in a large state is one that has lead us to our current situation. His preference for a system where democratic control could be better used against politicians and bureaucrats who fail us is certainly a popular one.

While his policy solutions have begun to fall out of favor to a renewed Keynesianism in international policy circles, his ideas still give us reason to stop and ask, “What exactly is the problem?” and “Should the state be fixing it?”.