It’s never been easier for us to obtain information in today’s digital age. But at the same time, it’s never been more difficult for us to organize, synthesize, and make sense of all that information we have at our fingertips.

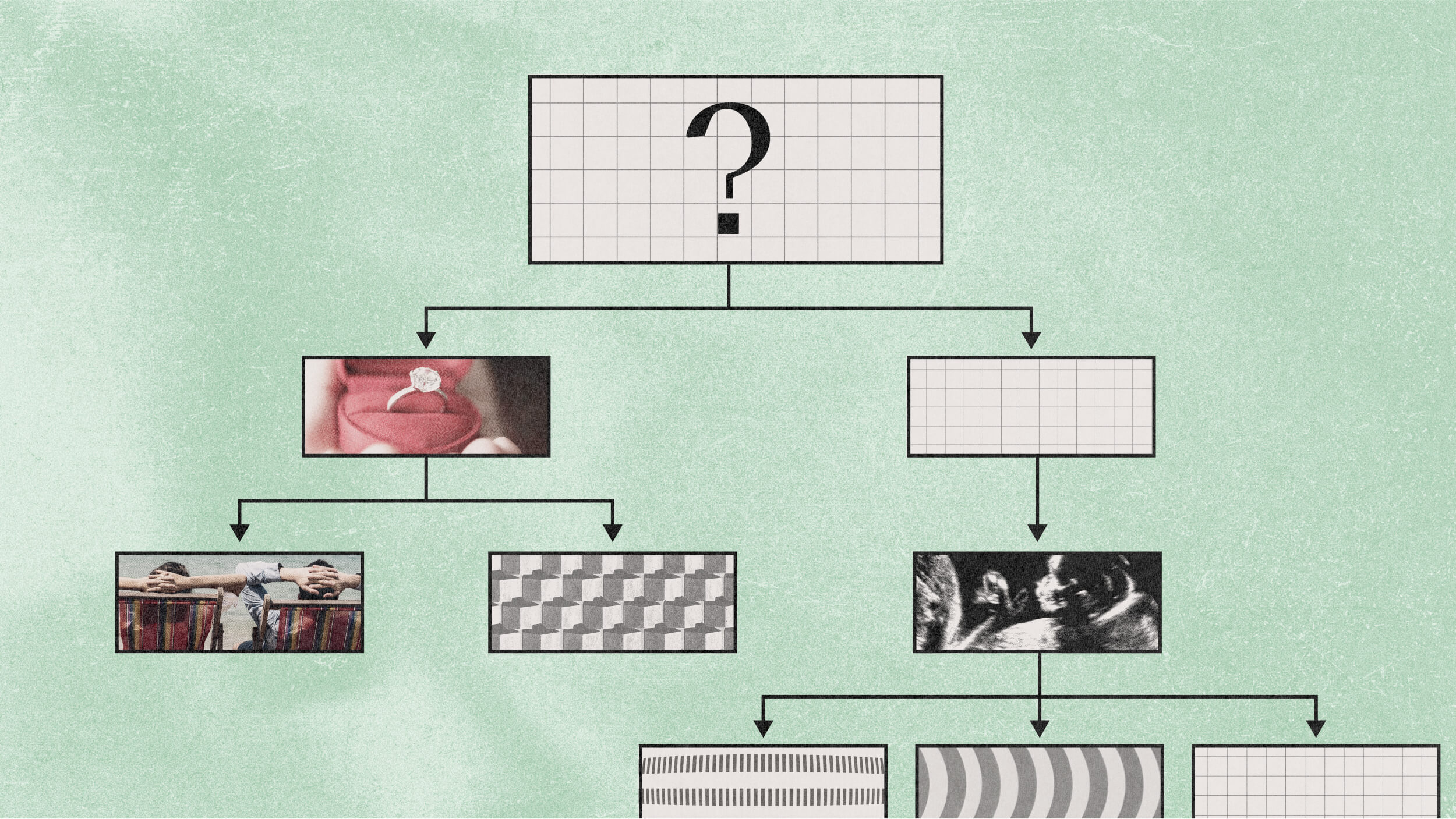

That’s why author Tiago Forte believes we need to build a “second brain,” or a personal system for knowledge management. To build up this system, Forte recommends using the CODE system: C for Capture, O for Organize, D for Distill, and E for Express.

Forte elaborates on his idea of the second brain — and much, much more — in this wide-ranging Big Think interview.

- My name is Tiago Forte. I'm the founder of Forte Labs, and author of the book "Building a Second Brain."

- How much information do we consume?

- I wrote this book in the first place to solve the problem of information overload: this classic issue that we've been hearing about now for 20 years, and yet, still have not found a solution: too much information, too many emails, too many messages, too many things to do, too many things to remember. So it's a solution to the fact that we are trying to run complex, modern lives, trying to take in and make sense of more information than ever on brains that haven't changed biologically in 200,000 years. Now, as I went about solving that problem, over time I started to realize, "Oh, this wasn't just a solution to one problem." It was actually this, what I sometimes call "cognitive system," this cognitive exoskeleton, this system that people could use and are using to create better work, to make better decisions, to be more productive, to save time. And so it started as the solution to a problem, and over time became kind of this entire methodology of how to do creative work in an environment of information abundance. It's really difficult to wrap your head around just how much information we intake every day- it's really kind of staggering. If you were going to try to quantify how much information the average modern human, the average knowledge worker just consumes, just takes in, it depends how you measure it, but a couple of the most staggering statistics are that if you measured it almost like as if it was on a computer, it would come out to over 30 gigabytes. 30 gigabytes, that's like a solid size hard drive that is coming into your five senses each and every day. By another measure, it was the equivalent of 174 newspapers: Imagine waking up every morning and reading 174 newspapers from front to back. Well, you don't have to imagine it, you do. That is literally what you do each and every day when you look at the emails you receive, the messages you receive, the sights and sounds, the audio, in podcasts, audio books, the reading you do, the communication you do. It is truly an inhuman amount of data, which is why we are in the situation that we're in now. There's an economist, his name was Herbert Simon, in the mid-20th century, and he has this quote that I think really sheds light on what is going on here, which is, he says, "An abundance of information creates a poverty of attention," right? The more and more information that we have the option of attending to, the more that consumes a certain resource. The resource it consumes is attention, and that's an issue because as a resource, attention is incredibly scarce. It's even more scarce than time, right? In a day you have 24 hours, but that doesn't mean you have a 24 hours of attention. In fact, many days might be so chaotic and frenetic, you might have zero attention-the whole day might just be putting out fires and running from one thing to the next. And so attention is our most rare and, therefore, precious attention, and it's what's being consumed by all of these companies and apps and social media platforms that consume it. That's what they're after, right? Even more important, even more valuable to them than the dollars in your pocket, is your attention. That is the very fuel of the internet, the fuel of the modern economy. They're going for engagement. Engagement is the currency of the modern world, and if you want to avoid giving away all of that attention to everyone who asks for it, every company that demands it, you have to kind of step back and create a bit of a filter. You really have to create a buffer between what I sometimes think of as the 'media storm,' this constant tempest of information, step back into your little cottage and ask, "What do I really want to let in here? What actually makes my life better? What actually makes me healthier? What makes me wiser?" Because if you just take in what all of these platforms think you should take in, I can guarantee you that is not going to naturally make you healthier and happier and wiser.

- Why did history's great minds keep 'commonplace books'?

- I started researching: I wonder if anyone else in the past ever had this problem? We can't be the first people to ever have too much information to manage. So I went back through history at different stages when there was a lot of change: when society was changing, the economy was changing, the way that we lived was changing. Went back to the Industrial Revolution, to the Enlightenment, to the Renaissance, and it turned out throughout history again and again, every time humanity faced too much change and too much information going on around them, they turned to the same solution. They turned to the solution, this thing called a 'commonplace book.' The word "commonplace" actually goes all the way back to ancient Greek times when the ancient Greek assemblies needed a common place, a centralized place to keep all the information that they needed to manage their democracy. But again and again, most recently in the Industrial Revolution in the 17th, 18th, 19th centuries, people would keep a notebook, a paper almost like a journal, except it wasn't just like a diary. It wasn't just a place for them to pour out their personal thoughts and reflections. It was a place for them to keep a much wider variety of things: quotes and Bible verses and recipes and bits of advice and wisdom. They would even put a leaf that they found in the garden or later on a photograph. It became this central repository of all the information and content that was meaningful to them. Some of history's greatest figures, I mean, Leonardo da Vinci is very well known for having, I think, around a dozen different notebooks that documented an entire lifetime of learning and discovery and research. Later on was John Locke, the English philosopher, who actually was so passionate about commonplace books, later in his life, he published a book on how to make commonplace books; it's one of the few examples of that we have. And then more recently, well-known authors, science fiction authors like Octavia Butler, used it to research their characters and the science that went into the science fiction. Really it's kind of a who's who of characters going back in time. Sometimes they didn't give us that many details. They didn't talk that much about it, they would just make these small, little references to it, but I would dare to say that most of the most prolific and impactful artists, writers, poets, musicians throughout history had some kind of book or note-taking system that was their place to develop their work in process before it was ready for publication, and that's how it was so good by the time that it was ready to be shared. And the reason that was so effective is most information that we have access to comes from some outside authority- it's a school or it's a corporation telling us what's important. Well, a commonplace book is the one place where you control the narrative. You decide what goes in and what doesn't. You decide what it means. It's the one place you control, and you can make sense of all the stuff happening around you. And what I'm trying to do essentially is reinvent that age-old practice in digital form for modern lives and modern work. So we have this very clear historical precedent, but there's one big difference between Leonardo da Vinci and John Locke and Octavia Butler and us, which is that these people were full-time creatives. They were artists. They could dedicate all of their time to taking notes and reading, and writing poetry, and sketching, and drawing. I don't know about you, but I can't afford to spend 100% of my time in kind of creative ideation. My work is creative- as a knowledge worker, I have to solve creative problems- but it has to be done productively. It has to be done efficiently. It has to be done in just a few minutes at a time, in the in-between spaces of phone calls and meetings and my tasks and to-dos and projects. So what that means for us is it has to be something that's leveraged by technology. Think about what modern technology allows us to do: First of all, we keep a world-class note-taking device called a smartphone with us almost 24/7. We don't have to scramble and look for a piece of paper or a notebook and a pen. We always have that thing with us. We can save not only texts, we can save photographs, we can save links, attachments, gifs, videos, almost any kind of media, not just handwriting. And third, and maybe most importantly, we have this just incredible tool called search. You can organize your notes, and I have a few ways of doing that, but it doesn't have to be the most precise, rigid, formulaic way of organizing your notes. It can be a little loose and carefree because you have the incredible power of search to find anything you need, anything you've ever saved or taken note of in the future.

- What is the CODE framework?

- My message to you is that you need a second brain: A second brain is a personal system for knowledge management. What is knowledge management? It's note-taking. It's saving little bits of material and content and information from both your physical environment, but more importantly, your digital environment, and also your own thoughts, to cultivate and retrieve and review it over time. The very heart and soul of your second brain is the habits and the behaviors, the actions that you take to keep it alive, to keep it running and moving. And the four essential steps that you have to take to keep your second brain relevant follow the CODE framework: C-O-D-E, which stand for the four essential steps of really the creative process. I have a creative process. You have a creative process. Throughout history, anyone who had any, even a little bit of creativity, had a creative process. So, the four steps that make that up are: C for Capture, O for Organize, D for Distill, and E for Express. Those essentially describe how information comes in on one side, gets captured- how that information gets structured, how it gets organized, that's the O, how that information gets distilled, refined down to its very essence, the most important, relevant, actionable points, and then finally, the end result, the purpose of the creative process, is ultimately expression, which is the E. What are we doing all this for? The reason we're doing all this, the reason it's worth it, is to express ourselves: to express our ideas, to express our voice, to express our message, to make what we have to say more powerful, more effective, more compelling, more persuasive. I don't care if you're in marketing and sales or if you're in engineering, or if you're in HR, or if you're in legal, there is someone in your life that you are responsible for communicating with effectively. The information and the content that you save in your second brain is simply the supporting material that you need to make that communication more effective.

- How do we determine what is important to capture?

- The first question that a lot of people have when they embark on digital note-taking is: 'What should I capture? What is worth noting down? What should I save?' And I have four criteria that, in my coaching and in my teaching, I've found are the most effective: The first one is, what's inspiring? You can google the answer to a question. If you need to know the population of France, just google that. There's no reason to write that down. But you can't Google a feeling, and think how often what you're looking for is really a feeling. You need a dose of inspiration. You need a dose of motivation. You need some relief. You need a break from what you're working on. Often what we're actually seeking when we seek information is a feeling- qnd there's something you can do about that. You can save content that evokes those feelings. Save a photograph that just inspires you. Save some lines from a poem or a song. Save a story that moves you, that touches you, that means something to you. It's really difficult to do creative work when you're not feeling it, when it's not resonating with something inside you. It really takes something from inside you to do genuinely creative work. Well, you can have a place where you keep all of your favorite things, the favorite things that inspire you, and that's why that's the first criteria. Now let's go to the opposite end of the spectrum: Sometimes the information you wanna save in your notes is not inspiring at all. It's like data in a spreadsheet, or it's some specifications for a product you're working on, or it's the contact information for a service provider, a lawyer, a doctor, something like that. You wouldn't say that it really moves you in any way, but you have to keep it for practical purposes, and that is a great use case for your second brain as well. What are the little bits of content that you know you're gonna need in the future, that you know you're gonna need to reference because it's just very detailed and specific? Sometimes it's maintenance information for your car. Recently we had to look up the model of the air filters that go into our HVAC system in our home. This kind of stuff that you don't want to use your precious brain space to memorize, but that you know at some point in the future is going to be essential. The third criteria that I like to use is things that are personal. Think about all of the content that you can find using a search engine. Anything that you can find on Google has no competitive advantage to knowing it because everyone else in the world has access to it, right? You don't need to write those things down. The stuff on the internet doesn't need to be be saved. But now think about the knowledge and the wisdom that is created out of your life experiences. If you've ever lost a job or had a failure or a disappointment, there are certain lessons, certain bits of, I would say, wisdom that sunk into- almost your soul, life lessons and little bits of perspective that even if you told them to someone else, it might not make sense to them. It only makes sense to you because it's in the context of your personal experience. Think about failures and mistakes but also successes you've had. What did you learn from victories? What did you learn about what works? What did you learn about what is needed for you to do your best work? Both the negative stuff and the positive stuff, as long as it comes from your personal life experience, that's knowledge that no one else in the world has access to or doesn't mean the same thing to them. That's the kind of stuff that you want to write in your notes and revisit over time because it really reveals things to you about who you are. And finally, the fourth criteria is things that are surprising. Think about this for a sec: If you read something in a book, and it doesn't surprise you, there's no reason to highlight it or write it down because if it didn't surprise you, that means you already knew it at some level, and if you already knew it, then why write it down? A great barometer for the things that are worth saving is things that surprise you, things that are genuinely novel, things that you never encountered before. You never thought about it quite that way before. Often, these are things whose meaning is initially unclear. You might read a quote in a book, and you might even disagree with it. You might even say, "Actually, I think this is wrong, but it evokes something in me that surprises me. It makes my mind kind of perk up and pay attention." That is a great example of things you should save in your second brain because often what that is, is you're subconscious telling you there's something here. There's something valuable or important or something relevant to you even before your logical mind knows what's going on. You can listen to those subconscious kind of decisions by noticing what surprises you and capturing that. I always think about a term from information theory, which is called the "signal in the noise." Okay, now think about this: Anytime there's- Let's say you're listening to a radio program- there's a lot of noise. There's the background static, maybe there's sounds in the background, there's "ums" and "ahs," all this data that just doesn't matter, that makes no difference. But there's also a signal. In that case, listening to a radio program, the signal is the words coming out of the guests' or the host's mouth. As long as you can hear what they're saying, all the background noise doesn't matter. Now think about how that applies to the rest of your life: There's always noise, and there's always a signal. Let's say you're reading a book: Not every single idea in a book is equally valuable. It's kind of obvious, isn't it? Not every single claim or statistic or fact that the author cites is equally important. If you're listening to a podcast, not every answer that the guest being interviewed has is equally valuable. Now apply this to everything: class you take, a seminar you attend, a conference you go to, a meeting you have with a colleague or your boss. Don't tell them this, but not every single word, not every single minute in that entire meeting is equally valuable. So what does that mean? It means that it really falls to you. It falls to you, the responsibility of finding the signal and the noise. I often notice that I'll read a book or read an article, or listen to an audio book, and write down just a few things. Like three to five bullet points is probably a typical amount of notes that I'll take, and what that represents is me reaching in, ignoring 95%, 98%, maybe even 99% of that content, and extracting the signal that is most relevant to me, which, by the way, might not be the same for everyone. You might have a different signal listening to the same piece of content, or reading the same piece of content, which is why we have to do this for ourselves. We have to take responsibility and agency for our own information stream and decide the bits of information that are most relevant to us based on our projects, our goals, our priorities in life. I'm a big fan of Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist who also had many other endeavors that he was into, and I always wondered, I think the thing that most impressed me was how eclectic his interests were. He won the Nobel Prize in physics- that's a pretty good resume- but then he also published multiple bestselling books. He traveled around the world lecturing on physics to all sorts of universities and institutions. He even played the bongo and the conga drums in orchestras. I mean, this is someone who went really deep on one thing, which was physics, but that didn't mean he didn't have a very eclectic and varied life. He really had both, the best of both worlds. So I started reading. I read all his books, still didn't find the secret, and then I started reading his biographies. And there was one interview that he did that gave me just a little clue, one little clue as to how he did it. And what he said is that the way he did research was by keeping in mind what he called "his favorite problems." These were essentially open questions, these ongoing open questions that he had about physics but also about many other scientific fields and even other subjects. He would keep in mind these open questions, things like, 'How do you make a diagram of an electron?' Things like, 'How do you teach physics to an audience of young people?' Things like, 'What makes a successful marriage?' Once he had these open questions in mind, he just lived an interesting life. He traveled to countries that he felt like traveling to. He read papers that he was interested in. And what he would do is every time he came across an interesting scientific study or an interesting technique or an interesting takeaway, he would just ask himself, in the back of his mind, "Does this have any application to one of my favorite problems? Is there any open question that I already have that this answer, that the solution that I'm looking at, can just be applied to?" And it's kind of a random way of looking for matches between questions and answers, problems and solutions. And most of the time, there wouldn't be a fit, most of the time the answer was nothing, but once in a while, this kind of open-ended way of working would yield fruit because he would make connections across domains. He would find a connection between a problem in one field and an answer in another field that no one had thought of, and in that moment, they would call him a genius. They would be amazed that he could ever see such a connection. So the relationship that has to our own work, often we're answering the same kinds of problems, the same kinds of questions over time. Let's say you're a web designer: You might have the open question, 'How do I design the header of a website that grabs people's attention?' Right? That is a problem that you are paid to solve again and again and again over time. And there's no one answer, there's no definitive solution, but you can collect answers, you can collect examples, collect case studies. Every single time you see a banner or a header that is good or is effective or gives you an idea, you save it, and that becomes this kind of, it's like this file of examples, this file of case studies, so when the moment comes to create your own website, you're not just trying to think about something out of the blue. You're going back to your archive of examples and pulling from things that have worked in the past, pulling from and borrowing from the work of others. The key is you have to give yourself permission to use any kind of open question. You might only have a few kind of big picture, very philosophical, conceptual questions, but some of my favorite ones are things like, 'How do I exercise every day?' Things like, 'How do I spend time with my kids in a way that also gives us exercise?' Things like, 'How do I spend quality time with my wife when we have a kid and a second one on the way?' They're almost like, many people would say, mundane, maybe kind of boring everyday problems, right? They're not these grand, philosophical things. I really like to mix them. I'll have conceptual question right next to a business question, right next to a personal question, right next to a psychology question, right next to a home maintenance question. With this mix of questions, with different aspects in different areas of my life, no matter what mood I'm in or how much energy I have, or how I feel, I can just turn my attention to different aspects of my life or my work, and I always have an interesting avenue to explore.

- What are the benefits and limitations of capturing?

- It's really incredible. I started researching this, and I found that there are just so many benefits to writing things down. Just that simple act of getting these thoughts and ideas and feelings, which are often kind of these vague, jumbled up notions in our head, and externalizing them, offloading them from our minds into some external medium, whether that's paper or software, has benefits for your peace of mind. It has actual health benefits. There's been studies that have shown that your blood pressure will be lower. You'll have less anxiety. You'll live longer. I mean, these kinds of things, if there was a magic pill that promised these benefits, you'd be like, "Give it to me. I don't care what it costs." And I'm telling you, you can access these benefits for free, right now, with nothing more than a paper and pencil or a note-taking app. All you have to do is get those off your brain. No one has to read what you write down. You don't even have to revisit it. You get most of the benefits just in that instantaneous moment of writing things down. Now, my work is all about, first, getting the benefits of writing things down but also getting a second round of benefits, which is the benefits of retrieving and recalling and reviewing. So I really think you can get the benefits twice, but it's important to realize that as soon as you begin writing down, right in that moment, you are starting to feel more relief. You're starting to feel less stress. And your body, in a very real sense, your body and your mind, are letting go. They're letting go of having to constantly have those thoughts cycling around your head again and again because you know it's in some external place that it can be revisited if you ever need it. Let's talk about the limits of digital note-taking for a second, which could illuminate what they are useful for, and what they're not. There's a couple things here: First, the extent to which you find these techniques useful depends on the season of your life. I find that I really turn to knowledge management during periods of intense change. When I first get a new job, those first few days and weeks, you're just trying to find your bearings; there's so much information coming at me, I just need a place to put it while I kind of make sense of things. When I am living somewhere new, when I move to a new city, there's all this new information coming at me. When we had our first kid, there was so much information that I had to learn. Those are moments that I especially lean on knowledge management. Even when I look across the arc of my career, in my earlier years, mostly my 20s, early 30s, where I was still kind of finding my direction, finding what I wanted to do as my career, I was note-taking across such a wide variety of topics, and I was saving almost everything because I just didn't know what was gonna be useful, whereas later, a little bit later in life, I find that I'm more harvesting. I'm now capitalizing on the knowledge that I saved back then, and my rate of new note creation of knowledge capture has way slowed down. Now, something could happen in my life: Let's say I enter a new line of business or enter a new field, or I dunno, have some big life change that it ramps up again. But it's not that you perfectly do the same number of things all the time, kind of forever. It waxes and wanes just like any other habit or routine or ritual that you turn to in your life. I'd also say that there are situations where what's most important is not to perfectly capture specific pieces of information. So for example, I used to take digital notes when I was talking to people in face-to-face, one-on-one meetings. Let's say I met someone for coffee or we were in the same city. I'd be there on my computer, and I noticed over time that they were kind of distracted. They were looking at my computer. They were looking at me. They kind of- It seemed like they didn't really know if I was listening. And eventually I realized, "Oh, even if I tell them, 'Oh, I'm taking notes. I'm listening intently. Oh, this is just my note-taking application,'" there's something, and, in fact, studies have shown that just the presence, the mere presence of a digital device, makes you distracted. Isn't that incredible? Even if it's off, even if it's on silent, even if you're not even, you don't even think you're paying attention to it, that phone sitting on the table, there's a little part of your brain that is constantly monitoring it, wondering, "Oh, what's happening? Is there a notification? Is there a message? Should I check social media?" Whatever it is. And so I made a policy for myself that I would take all notes in personal meetings on paper. It was more important to, the priority in that moment was that the person felt heard, and felt like I was present with them, and felt like I was fully paying attention. That was more important than my perfect documentation of every detail. Now, after the meeting is done, I do go home and I take a photograph of that notebook page, which then saves it in my note-taking application, where it can be found anytime in the future, so I kind of have the best of both worlds, but I would say really pay attention to what is most important in any given situation. If it's documentation and recordkeeping, prioritize your notes. If it's presence, if it's focus, you may want to take a different approach.

- How do we organize what has been captured?

- Often the question that people have once they've begun taking notes is, "How should I organize them?" This is the big question that leads a lot of people to me, is, "I have digital notes, I have files, but they're just this chaotic jumble. I don't know what to do with them." I've developed a framework for that- it's called PARA, which stands for Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives, which is a system for organizing digital information. And when I say digital information, I mean all of it, across your entire digital life, all the kinds of content from wherever it comes from, for whatever purpose, saved in whatever format. And the main principle of PARA is that, at any given time, with all the content that you saved, even if you are extremely picky, even if you only saved the most, most, most important stuff, there will always be more than you can pay attention to at any given time, okay? So what we want to do is just distinguish, what is the material that matters? And for me, that's Projects, right? The outcomes, the goals I'm working toward right now. Things that are active. There's a deadline. There's people waiting on me. They're kind of like, they're the equivalent of a pan on the stove that's cooking your food. You don't want it to burn, so it's very active and relevant. And then there's everything else, all the other categories, which in my framework, there's three: Areas of Responsibility, things that you're responsible for but that are more long term that you're kind of managing slowly over time. Resources, which is everything else, everything you're learning about, curious about, researching, reading about. And then finally, the last A is for Archives, which is anything from the previous three categories that is no longer active, right? And generally, Projects will be the smallest category because just think about it: The information that you need right now to move forward your current projects, this moment, is actually quite small. You only need a few details. You only need just a little bit of context. The content that you need to manage your Areas is a little bit bigger, things like home maintenance records, car maintenance records, things to do with my kids, things to do with my pet. Those aren't quite as urgent. They're more kind of long term over time. Resources is even bigger because I'm curious about a lot of things. I'm interested in a lot of things over a long period of time. And Archives is the biggest because archives is like the cold storage- it's every single thing in the past that I've read, thought about, and noted down, every project I've worked on, every goal I've achieved, but that's okay. See, the archives can grow as big as they want. There can be hundreds, thousands of gigabytes, it doesn't matter because they're down in the basement. They're in the cold storage, not distracting me, not taking up my attention, not pulling me away from what is active right now. The archives can really grow as big as you want as long as they don't distract from your current goals and priorities. Now you might be wondering, "How does something like PARA, which helps me organize my notes and my files, have to do with creativity?" There's actually a very direct connection, and this is something I learned from my father. My father is a professional artist, a painter, has been his entire life, but he's also one of the most productive people I've ever met. I always noticed that people would have this image of my father, "Oh, he must be so imaginative, just wandering around the house, kind of head in the clouds," and that just could not be further from the truth. In order to do his art and to be prolific with four kids, and raising four kids in Southern California, he had to have rules and routines and structures. Everything had to be very well planned out, so my dad treated every painting as a project. It wasn't just this thing that he kinda got to whenever he felt like it. He would really think about what was needed to move a project, a painting, forward. What were the colors he would need? What were the elements in the still life that he was painting? What was the time that he would need to set aside to finish it? And I'd say this is true of any creative endeavor- you can't just leave it up to chance. You can't just leave it purely up to being in the right mood. If you want to make a living from your creativity, if you want to actually reach completion, if you want it to reach a state that it can be shared with others and have an impact on something or someone outside of yourself, you have to finish. Sooner or later, you have to complete it, and that's where productivity is kind of the other half of the coin of creativity. You could be the most creative person in the entire world. If you never finish anything, if you never publish or ship or present or display, or whatever it is, no one would ever know, okay? Productivity is the essential second half of creativity. So what PARA does is constantly have you ask yourself, "What is the content, the material, the raw ideas that are strictly needed for your current projects?" If the answer is, "Yes, there is some relevance," you should put that piece of content directly in the folder or the notebook or the tag for that specific project. Don't just hope that you'll remember it at some point in the future- just put it right there. And if it's not relevant to any project, put it in one of the other less important, less visible categories of Areas, Resources, and Archives. So you're essentially constantly making the distinction, "What ideas and material do I need to move forward?" Put it over here. And, "What do I not?" and put it out of sight and out of mind.

- What is the distillation process?

- Here's how distillation works: In the notes that you've saved, even if you've been very picky and very selective, there's gonna be too much. The human attention span is so short, often just a few seconds- the amount that we can hold in our minds is just maybe six or seven or eight digits. It's so tiny, that if you want to be able to actually work with all these notes, you have to distill them, you have to summarize them, you have to refine them down, which in my approach is as simple as making a highlight. What is the key point in this paragraph? What is the key idea on this page? What is the key action step or takeaway from this entire class that I've taken or meeting that I've attended? Imagine you have a suitcase full of ideas, but it has no handles- it's gonna be really hard to do anything with that. You're gonna be kinda grappling it, and it's gonna be really awkward. So you really just need a handle. You need a specific place where you can reach and grab that suitcase and be able to move it around and pull it where you want to go. That's what a highlight is for a note. When you look in a note, might be 500 words, might be 1,000 words. It's like this wall of text. It's kind of instantly overwhelming. What your mind needs is a place to attach. It needs a highlight or a bolded or an underlined phrase that tells you, "This is what this note is trying to say. This is the headline. This is the main takeaway." When you see that main takeaway, that main point, you can decide right in that moment to keep reading, to go deeper into that source, and if it's not relevant, you can just put it aside and go onto something else. That is the value of distilling your notes, and it's essential. The reason distillation is important is because of something called 'discoverability.' Discoverability is this principle from information science that refers to your ability to find what you're looking for. It's actually kinda straightforward. So when it comes to digital notes, there's two important tools that we have to enhance discoverability. The first one is search; search is absolutely crucial. The ability to type in a word or just a few words and instantly, just like Google or a search engine on the web, find only the notes that are relevant to that. And the other one is distilling, is highlighting, because when a note comes up, the word you're looking for might not actually be included in the search. It might not actually be included in the note itself, so you have to be able to kind of scan and kind of glance over a body of text and find only the points that are most relevant. Well, those will be the points that you highlighted previously, and thus, you're using search and highlights in a very synergistic way, each one contributing its strengths and what it does best.

- What are the stages of expression?

- At the end of the creative process, we arrive at E for Express, and this is really what it's all about: This is really the entire purpose of all of this. The reason it's worth doing is the ability to express your voice, your ideas, your message better. Now, I find that expression is challenging. We are not taught. We're not taught in school, we're not taught in most companies that our voice matters, that what we have to say matters, that our message is something that can really reach people and really change them. And so, I often see people moving over time through three stages of expression: You can think of them as beginner, intermediate, and advanced. The first one is simply remembering. Have you ever been in a meeting, let's say with your team or some colleagues, and you express an opinion and someone says, "Oh, well, how do you know?" or, "What makes you think that?" And you just think, "Oh, if I had that one data point, that one fact, that one statistic, or even just that one example, my point would be made so powerfully, so convincingly." That's the first usage of a second brain. Imagine if you could just say, I often do this in the midst of the meeting, in the midst of while we're talking, I just do a quick search on my computer or even on my mobile device, and I find the one piece of evidence- it's essentially what it is- is evidence to back up what I'm saying and make what I'm saying more than an opinion or just something I said, make it an actual point of view that has power and credibility that others can support and agree with me on. After you've been collecting ideas in your second brain for a while, what often happens is it reaches a kind of critical mass. You start to notice these different notes you save, sometimes on very different subjects, from very different scenarios and situations, they start to connect. You might realize, "Oh, this insight that I had about gardening in my backyard at home has an interesting parallel to how to organically grow my audience." These connections will cross the boundaries from one project to another, from one department of the business to another, even between your personal life and your work life. The same patterns tend to repeat again and again in your life, is my experience. And by saving all of these observations in one single, centralized place, your second brain, you drastically increase the odds that you're gonna notice how things connect and relate, and this is innovation, this is creativity, is not inventing something from nothing- it is just applying a tool or a technique or an insight from one domain, and then translating it to another one. That is the very essence of creativity. And then finally, there's a third stage, the most advanced stage, which is creating- after you've been remembering and retrieving, and then you've been connecting ideas together. Eventually, you reach a point where you realize, "There's something new that I have to say." There is some new point of view, a way of seeing either your organization or your business or your industry or the world at large, or some important issue or cause that is not quite the same as anyone else, and that's when people become creators. They start writing or blogging. They start a podcast. They write a book. They write a play. They design a website. They produce some sort of artifact, some knowledge artifact. These artifacts kind of encapsulate what they know in a concrete thing, whether physical or digital, that can go out into the world, and almost be like their ambassador. It can be the vehicle through which their ideas impact the world, and that is the ultimate and final and most advanced use of what I call a second brain. Sometimes when I say creativity or creation or creator, some people tend to disqualify themselves. They think, "Oh, well, I'm not a blogger. I'm not a YouTuber. I don't teach online courses or whatever." And here's the thing, is online creators, people who make a living by publishing content online, they're just the leading edge. They're the leading edge of something that is coming to all of us, I promise you. In the future, if not already, all of us are going to have to create content. Whether that content is shared publicly on the internet or just to your organization or your industry, or even just to one person, it's content. We're going to have to get used to putting our ideas on display, getting feedback from other people, their critiques, their perspectives, their points of view, and then incorporating that feedback back into our thinking, and make one more pass, one more iteration. This is just the way that things are moving. Work is becoming more collaborative, it's becoming more public, it's becoming more iterative, where it's not about, and really it never was, about the lone genius going into the studio or going into the cave, staying there for weeks and months, and then emerging with this perfectly formed thing that they created. That era no longer exists, and maybe never existed. Today, it's all about collaboration. Whether it's a film you're working on, whether it is a piece of technology that your company sells, whether it is a policy that you're writing to be instituted as law, it doesn't matter. These big outcomes, these big impacts, come from the collective minds of people. They come from groups. Now what you bring to that group, what you bring to the table, is your body of work, this body of knowledge that you've collected, not just something you thought about in the moment in a brainstorm, but something you've been cultivating and growing over time, so that when you sit down at that table, it's not just, "Hey, let's come up with some ideas. What do you guys think?" It's like, "No, let's bring our notes to the table, put them on the table, compare and contrast them, and actually build something that matters, that is novel and meaningful." That's, I think, really where things are headed, and I think anyone, no matter what their profession, no matter what their field, needs to get used to this very collaborative and very iterative and experimental way of working.

- How can we make the most out of CODE?

- We are knowledge workers: people who manage large amounts of information to do our jobs and to solve problems- but there's something funny I've always noticed about knowledge work, which is we don't have a culture of systematic improvement. Think about it: If you're a plumber, if you do any kind of skilled manual trade, you know the skills that you have to acquire to get better. Think about engineers. Think about electricians. When it comes to physical things, you can systematically improve what you do to get better and better at it over time, but when it comes to digital knowledge work, it's so abstract. It's so conceptual. Can you really say, for example, that you're getting better at managing your email? Are you really getting better at managing your calendar? Are you getting better at taking notes? I mean, these are kind of the basic moves, the fundamental building blocks of knowledge work, aren't they? Isn't that how we're spending most of our time, most of our days? And yet, for most people, I don't think we're getting better at those things at all. In fact, we're just getting more and more overwhelmed over time, so, in a way, we're getting worse and worse over time. We don't have a culture of systematic improvement when it comes to knowledge work, and that's largely what I'm trying to provide. In my view, knowledge work is about CODE. It's about, at the most basic level, we are all taking in inputs, processing and refining them in some way, and then having some kind of output on the other end. And once you break it down into, for example, the four steps of CODE, you can practice each of those four activities. You can get better at them. You can use tools and software that makes you more effective at them. If you get better at the four steps of CODE, you will unavoidably get so much better at the final outputs of knowledge work, which then will accelerate your career, enhance your reputation. Really what we're looking for is bringing knowledge work down to a process that anyone can understand and, therefore, improve. One of the reasons that it's so powerful to save it all in one place- all the learning, all the resources, all the references, all the research- that centralization is so powerful because once you start doing that, you very quickly realize just how much you have. With all this stuff spread out over a million places, you can tell yourself that you're not ready, that you need to do more research, that you need more planning and preparation, but once it's all in one place, and you step back and you look at just the staggering amount of information, knowledge, and even wisdom that you already have, it's kind of like this moment of confrontation where you can't really say, "I don't have enough." I mean, look at this: Look at all that you've collected, all that you've acquired. And so sometimes people become information hoarders where they fall in love with the C in CODE. They fall in love with capturing because there is a bit of pleasure- it's like hunting. You get that little tidbit of knowledge, you save it in your little special place, and you're like, "Ah, I made progress. I acquired something valuable." But what I want to do is have people fall in love with the end of the process. The beginning of the process is great. The end of the process is even much, much better because that's when your thinking comes to fruition. That's when it all gets to live and stand on its own two feet as something apart from yourself. That's when you get other people's appreciation and respect. That's when you get a higher income or sales or some whatever goal you're trying to achieve. And it's really just a matter of pushing as much of your effort from CODE- which is where people tend to concentrate because that's the easiest, taking notes in the first place- just don't even spend more time. Don't even put in more effort, just redistribute the effort. Push it from C to Organize, to Distill, and then to Express. We're already spending 10, 12, 14 hours a day consuming and interacting with media on our devices. That's already the case, especially after COVID. You don't need to spend more time. In fact, you should probably spend less time, but it just needs to be rebalanced. Less consumption, more creation. Less passive, more active. Less just whatever the authority told me is important, and more deciding for yourself what is important. That is what is going to put you in control of your own destiny.

- What are divergence and convergence?

- There's another idea that I want to introduce you to, which is divergence and convergence. This is a concept that I borrowed from design thinking, which was originally applied to designers building products, and today, I think, is really applicable to all of us, and it works like this: Any creative work can really be boiled down into just two stages. They're kind of like a pendulum; they swing back and forth, back and forth. The first stage is divergence. The reason we use the word divergence is the number of options that you are considering, that you are thinking about, that you're looking at, is diverging from the starting point. Let's say you're starting a project to put on a conference: You're gonna organize and host a conference for your industry. Where you wanna start is with divergence by considering many different possibilities. You don't want to come to solutions too quickly. You want to think about different venues. You wanna look at what other kinds of events have done. You want to consider different agendas, different formats for breakout sessions, for the keynotes, for the different groups that people form into. You want to really expose yourself, kind of open yourself up to the universe of possibilities that exist so that you can find the best: the best ideas, the best examples, the best practices that other people have already discovered so you don't have to reinvent the wheel. Divergence is what we normally think of when we think about the imagination or creativity. It's this kind of free-form, completely open-minded, radically imaginative process. As long as you're in divergence phase, you should just embrace it. Any rabbit hole, just go down it. Any distraction, be distracted. Go follow that new thing, that new shiny object. Talk to people. Walk in the street. Find ways to absorb and expose yourself to unexpected, surprising things. That's what will lead to new ideas. That is the right way to operate when you're in divergence mode. But divergence is really only half of the equation- there's another part, another step that is just as important, which is convergence, okay? If you want this project, or in this case, this event, to actually happen, to reach completion, you have to, at some point or another, start converging. You start eliminating options. You start cutting off certain pathways. You start removing certain parts and certain pieces of the agenda so that you can arrive at a final point, a final destination, which is the final event of the event itself. So, the reason this is important is you really want to know in any given moment, in any given day, which mode you're in because they require completely different approaches. If today is a divergent day, or this work session or this hour or this minute is a divergent minute, you should open up the doors and windows, put on loud, crazy music, talk to people. Get exposure to as many different diverse ideas as you can- that is what divergence is all about. But, the moment you decide, "Okay, I've collected enough. I've researched enough. It's time to converge," close the windows, close the doors, put on your noise canceling headphones, silence your phone. It's time to shut off all this new stuff, these new sources of information, and just drive toward the final outcome. That is what it means to be both creative and productive: what it means to both research the best of what's out there, but also put forth your own best effort, divergence followed by convergence, and then back and forth, back and forth, until you finally arrive where you're going. A really powerful way of thinking about divergence is about constraints. Just because divergence is kind of imaginative and kind of free-form doesn't mean it doesn't have constraints. So one very mundane example: I found that when I am browsing Netflix or any streaming service for something to watch, the more options I consider, the less likely I'm going to choose any of them. Have you ever noticed this? It's kind of like this with everything, there's something called the "paradox of choice." If you consider too many restaurants, it becomes too much information, too much complexity, and you end up choosing none. If you consider too many places to vacation, if you consider activities to do with your friends, too many options under consideration multiplies the effort so much that you end up just kind of collapsing in exhaustion. And so what I like to do is, before I've started, give myself a constraint. So with Netflix, I will tell myself, "I'm not allowed to consider more than five things to watch." As soon as I've considered five things, no matter what they are, I have to pick one of the five that I considered. Same thing with restaurants. I'll tell my wife often, instead of, "Oh, where do you feel like eating?" Which, always, quickly becomes this infinite discussion of all the possibilities, I give her a multiple choice question, "Would you rather have Thai, pizza, or Chinese food?" and then she just picks one of the choices, which is easier for me and also easier for her because we've constrained the choices. So, what I would say is if you have a tendency to kind of diverge forever, give yourself constraints. Say, "I'm gonna consider this many options," or it can be a constraint of time. "I'm gonna spend this many minutes or this many hours researching, planning, trying to decide. Once that time limit is up, I'm just gonna choose." Constraints are really essential because you can really spend forever diverging. We've all met that person: You talk to them, "Oh, they're researching some obscure topic." A year later, "Oh, what are you doing?" "Oh, I'm still researching that thing." There's been no tangible signs of progress. Nothing has been published, nothing has been shared, no results, no outcomes, and you just start to kind of wonder, "I mean, are they really researching? Are they really making progress?" "Am I really researching? Am I really making progress?" I often say that learning and research is the most tempting form of procrastination 'cause as long as you're researching and learning and planning, you can tell yourself, "Oh, yeah, I'm making progress. Oh, yeah, I'm moving forward," when you're not. You're really just procrastinating with a very plausible-sounding excuse, and avoiding facing the really difficult thing, which is simply that moment that you decide to converge, and you decide to arrive at a conclusion. Many people, especially people who have many interests, are curious about many things, the kind of person that might consider building a second brain, tends to have more difficulty with convergence. They have so many things going on. They can see all the possibilities of what this thing they're working on could become that I think there's actually almost a form of grief. There's like a creative grief that comes in that moment where you have to ax the scene, you have to delete the paragraph, you have to remove the slides. It's like, "Oh, my babies, my children. I spent so much loving attention to bring them into the world, and now they're being being cut." It really is painful, and that's the case for myself. It's so hard for me to converge. There's a few ways that having a second brain makes convergence easier. The first way that digital notes can help you converge is by getting the thing you're working on, and breaking it up into smaller pieces, into smaller steps. Now here's the thing, you've heard that before. Probably going back to elementary school, your teacher told you, "Oh, if it's too hard, it's too big, break it down into smaller steps." But here's the thing, without a second brain, without a place to save those steps, just breaking it down into tiny pieces just makes it worse because you have to manage all the pieces. You have to keep track of all the pieces. You have to remember somehow where every little piece is, what its current status is, and how they all fit together. If you're trying to do all that in your first brain, your biological brain, it's not gonna work. Breaking things down into smaller steps only makes things worse if you do not have an external medium to save all of that detail in. The second way that a second brain can help you converge is a technique that Ernest Hemingway used for his writing. What he would do is, at the end of each writing session, instead of finishing, say, a paragraph or a page or a chapter and then putting down his writing utensil and moving on, he would start the next paragraph or have an idea of where the next page or the next chapter was gonna go, and only then would he finish the writing session and step away. You see what he's doing there? He's building himself a little bridge, which is why I call this a "Hemingway Bridge," giving his future self a little starting point, a little clue, as to what to do next. He's giving his future self a gift because the next time he sits down to write, whether that is tomorrow or next week or next month, he's looking at a starting point. The thing we always want to avoid at all costs is the blank page, that terrifying blank screen where we have to just start somewhere. We can use a second brain, we can use digital notes, to create a Hemingway Bridge, by simply, every time we're about to finish for the day or finish before lunch, finish a work session, writing down the last thing we were working on, writing down our idea for what could come next, writing down just a little clue as to what the next step in that project may be. Now, of course, you need a place to write that down. You need a place to save it where you'll remember where you wrote it down in the first place, and that is what your second brain is for. You can think of your second brain as a collection of all the little bridges that you've built to all the future tasks and projects that you might wanna work on and revisit in the future. And finally, we have a third way that a second brain can help you converge, which is called "dialing down the scope." This really comes from my days in Silicon Valley when I worked alongside software engineers. Software engineers in Silicon Valley have a very powerful way of working, which is once they've set the release date for the new version of the software they're working on, let's say, it's two weeks from now, as the date approaches, they start to realize they're not gonna make it. They've taken on too much. Does this sound familiar? "Oh my gosh, there's not enough time. There's not enough people. We have more to do than we have time to do it." In most teams, in most companies, what would they do? They would start to postpone the deadline, postpone the release date, postpone the publication date, the launch date. That's not what they do with software. With software, what they do is they drop scope, they dial down the scope. So the "scope" refers to all the new features they're building, okay? Instead of postponing the release date, which just can keep happening again and again, now it's next week, now it's next month, now it's next year, it's just infinitely postponing this important milestone- they just do less. They look at the collection of things that they've committed to, all the new features they want to build, and they drop the least important one. And then the deadline gets closer. They drop the next one and the next one, and the next one. They might drop 70% or 80% of the scope if needed, but the important thing is that the most important things, the most essential features, will get shipped. They will get released, and they'll get released on time. I really want all other knowledge fields to adopt this way of working. Imagine if as you approach your next deadline, it wasn't yet another postponement, yet another delay, it was a frank discussion, say, either just on your own or with your team: "What is less important here? What doesn't matter as much? What can be saved, not forever, not canceled, but saved for some future version, some future update or iteration?" Now how does a second brain come into play with that is you need a place to save the thing that you dropped. The part that got cut or removed or postponed or put on pause, you need a place to kind of keep that for safekeeping, and that's what your second brain is. Don't delete it. Don't throw it away. That was important material that you spent effort to create, but just save it for some future moment or some future project.

- When do we pivot between divergence and convergence?

- If you're wondering when it's time to switch, to pivot from divergence and convergence, it really depends on the situation. Often you have a deadline, you have a meeting with your boss or with the client. Often you're running out of time. Often some kind of external constraint is happening that it's time to stop doing more research, as tempting as that is, and sort of turn that corner where you essentially decide, "Okay, the material that I've collected is enough. The research I've done is enough. The number of options that I've considered is enough." Kinda has to come from an internal place of confidence that you have enough, you know enough, you've done enough, and now it's time to just sprint towards that finish line, and make that pivot into convergence mode. You wanna have many things going on at once. We've been told for years now that we need to focus, we need to monotask, we need to do deep work- which is true. It is important that we do deep, focused work, but there's kind of a flaw in that thinking, which is we live in a time of so much uncertainty, so much uncertainty at all levels of society, at all levels of companies, at all levels of the economy, that often if you're only doing one thing, you have one focus, say one project, and that project gets stuck- and it can be stuck for all sorts of reasons. You're waiting for approval. You're waiting for some event. You're waiting for a budget. You're waiting for someone to get back to you. If that's the only thing that you have going on, well, you are stuck, you're done. All you can do is just sit there and twiddle your thumbs and wait for that thing to get unblocked. One time, my Dad told me, he said, "Your generation, you always have so many balls in the air. You never just do one thing. You have a side gig over here, and then you have a job for a while, and then you're collaborating with a friend, and then you have this blog or you're on TikTok," or whatever it is. And at first, I thought, "Gosh, yeah, that is a problem." And then I thought, "You know what? Actually, that's the only way to do things these days." Our generation, our time now, is in an environment of so much change and uncertainty, we can't put all of our eggs in one basket. We can't put all of our chips on one square. We have to have multiple things going on, whether it's relationships, whether it's business endeavors, whether it's side gigs, because we have no idea what's gonna pan out. Now, how do you have many things going on, many projects, many gigs, and still have some peace of mind and still be able to sleep at night and not have all these things, these balls in the air, kind of keeping you up? To me, that's what a second brain is. A second brain is kind of like, it's like when you're playing a video game, and you hit pause. You can just hit that pause button, walk away, do something else, take a break, go do something else, come back, and just hit continue. It's almost like I have all my different projects and goals on pause, on save, and I can just pivot from one to the other. And the reason that I can just let one go and move to something else is it's preserved exactly how it is in a concrete medium outside my head. The fact that I can work inside of a note, that's really what I'm doing, the project is actually happening in the note, not in my head, means that the second I step away, it's saved, it's preserved, in a very evergreen format, which is a digital piece of software. So essentially a second brain can allow you to push forward on multiple different fronts, have many bets going on all at the same time, and still have the peace of mind that you don't have to keep track of all these different things going on using your fragile memory. I often find that most people have a strong bias- they have a tendency towards divergence or convergence. It's kind of something they're born with. Some are more divergent: They're just naturally spouting off ideas and going down rabbit holes, and every time you talk to them, they're onto something new, and they probably have a very good imagination. They can probably see possibilities that few other people can see. They're divergent people. Other people are convergent: They're often more practical, more numbers-oriented, more analytical, and they really like to just know the deadline, the timeline, the framework, the structure, follow the steps to get to the outcome. I think each of us has a natural bias, but we can also cultivate the other one, or alternatively, we can bring people into our life, friends, collaborators, colleagues, who compliment us. If you are divergent, you probably need a converger in your life somewhere to get you to kind of reach that state of completion and vice versa. Neither one is better. Neither one is superior. It's really about having the full diversity of human ways of thinking and human ways of being all brought to the table, all working together, and doing what they do best.

- Why are second brain practices important?

- Why do we have to think about divergence and convergence? Why do we need four steps to a creative process? The reason this is necessary at all is many of us have more autonomy than ever, don't we? I talk to people that work in the biggest, most traditional corporations, and even they have more autonomy than ever, autonomy for where they work. We're entering the remote work age- you can now work from the coffee shop, from your house, from a hotel, from a resort in some foreign country. We have more autonomy for when we work. It's not necessarily now the strict nine to five. We can work in the middle of the night, or we can work in the middle of the day, or we can take long breaks, or we can work a little bit at a time or in big chunks. We have more autonomy even as to who we work with. Internally, even inside companies, there's a lot of kind of free-form teams where people are connecting and collaborating even with people outside of their team or outside of their department. Really, there's this devolution of power. So much of the power and the agency is sort of trickling down. It used to belong only to the executives, only to the CEO, and now it's trickling down to all the rest of us- which is wonderful. It's a beautiful time to be alive. We have more control over how we work and when and where than ever- but there's another side to that coin. There's always a cost to more freedom, and that is we have to structure our own work. Think about it: No one is gonna structure your work for you. There's no boss necessarily looking over your shoulder, keeping track of every minute of your day. You have to decide: 'When do I start? When do I end? What are the chunks that I'm taking on in my commitments? What is the deadline or the delivery date that I'm committing to? What are the expectations that I'm setting? How am I communicating, in what format, through what channel, at what frequency?' I mean, talking about choice overload. So many of these decisions didn't used to be up to us. We just arrived at the office, and our boss or just the design of the office told us how to do these things. Now they're choices, they're decisions to make, which means more information to keep track of, more things to test, more experiments to run. This is really kind of the deeper purpose of my work, is to give people structures, to give people building blocks. You still have to decide how to put those building blocks together. It's like LEGOs. For some people, divergence and convergence is really most useful, for other people it's CODE. For other people, it's PARA. For other people, it's progressive summarization or intermediate packets, or any one of dozens of different things that I present in my book and in my work, but it's likely that a small number of them, just a few, are gonna be most impactful for you, and what that ultimately comes down to is just self-awareness. Do you know you? Do you know how you work, how your mind works, how your creativity works? That is going to be the ultimate determinant of what practices you adopt.

- What is the future of second brains?

- It's my belief that whether you call it personal knowledge management or digital note-taking, your second brains is a historic force. Has nothing to do with me. I think it would happen just the same without me, and without my book. It is coming. It's all signs are pointing to this wave coming across society of not using our minds to remember things, of leveraging software, of communicating and collaborating and creating things using technology. So it's coming one way or another. At most, my work and my book is sort of accelerating that. It's providing like an early entry point. A book is one of the most universal, accessible ways of spreading information, and I hope that's what my book does for the topic of second brains. But I see it coming, and in a funny way, the ultimate measure of success that I can envision is if no one talks about building a second brain- the book, the brand, the methodology. When a method, a way of thinking, becomes truly democratized, it disappears. It actually fades into the background. It dissolves into the culture. Something as simple- I love studying history. There was this thing that GM, General Motors, which was the most radical, forward-thinking, innovative business of the 1920s, 1920s and 1930s, they introduced management by objective, MBO, which was this idea that a company should have different departments, and each department should have goals, and they should work towards those goals. That's the whole idea- and it was radically innovative! People were like, "What? Objectives? Like, have objectives and track progress towards them?" Mind blown. If you say that to someone today, they'd be like, "Well, duh. Like, how else would you do things?" It's totally obvious because it's completely been absorbed into the everyday way that we think just naturally- and I think that will happen with digital note-taking. We'll reach the point that if someone says, this is the ultimate measure of success, that if someone says, "Oh, I'll keep that in mind," the person talking to them goes, "What? Why? Why would you do that? That's dumb." That would be like trying, like if you have to carry a bunch of equipment across town, and you try to like put it on your shoulders and just walk it down the street. It's pointless. Why take on that burden? Of course you're going to save knowledge externally. Of course you're going to offload details and your expertise into a place outside of your head. It's gonna be completely expected as part of the way we do things. Back when I was in college at San Diego State University, I worked at the Apple Store in Fashion Valley in San Diego, and one of the most popular books the whole time that I worked there was called "The Missing Manual." It was a whole series actually- there was the "iPhone Missing Manual," the "iPad Missing Manual," "the Mac Missing Manual." And I think of that because it kind of highlighted this interesting trend that new technology's coming out all the time, both hardware and software and online services, and no one really teaches us how to use them. Have you noticed? There is no really training program. Maybe a website will have some sort of tutorial. Maybe there will be sort of a getting started guide, but it's usually not very good. It's usually very basic. It's like how to start the very first few basic features, but then when you want to use something in a more sophisticated way, in a more powerful way, in a more leveraged way, you're kind of on your own. The company itself is not gonna really help you out. So I think that's inspired a huge cottage industry of YouTubers, bloggers, Instagram influencers, TikTokers who are filling in that void, and they're coming in and teaching us how to use both the software and the hardware. I'm doing that when it comes to digital note-taking apps and productivity apps in general, but it's really kind of the missing, it's the missing manual- it's the missing education. No one taught you in school, even at work, which you would think would be the venue that is most likely to give you these skills. They don't know how to use this technology; they're probably more behind than anyone. And so it really falls to the individual, and it falls to them on their own time, to pursue learning in how to use technology more effectively. But there's also, there's a problem, there's an issue here, which is the very people who would most benefit from this education, this training, are the least likely to access it. I've noticed this for years: They're just not even aware of it. They often can't even afford the technology that would be needed to actually put into practice what they're learning. They might be on social media, but they either don't have the time, or the bandwidth, or the awareness, or the support to use online content to educate themselves, to improve themselves, for one reason or another. This is sometimes referred to as the "digital divide." The digital divide is not just, "Oh, do you have a computer at home or not? Do you have computers at school or not?" It's really, more fundamentally, are you immersed in a culture where things like this are even talked about and valued? And do you have role models of what it means to be productive? Do you have models of what it means to leverage technology to capitalize on the value of your knowledge? These are very esoteric kind of abstract concepts. I think the answer is no. I think very, very few of us have access to this kind of culture except the very most elite knowledge workers. I mean, I myself learned this in Silicon Valley- Silicon Valley is 10 or 20 years ahead of everyone else. And these concepts even there, are new. So we have a long ways to go to sort of democratize this idea of a second brain, this idea that you don't have to do it all with your biological mind. You can extend your cognition through software, and by doing so, make it so much more powerful, and at the same time, unburden yourself from having to remember all these details- and that's really what I'm all about. We're living in an age where technology is becoming so incredibly powerful that it's not just like having a slightly better car or a slightly nicer house. These days, the divide is between people who are using technology to become almost superhuman. Think about someone who has mastered how to use a computer, who has an online presence, who maybe even has an online following, who can connect to anyone in the world, can access any piece of knowledge they want, has taken dozens of online courses on any topic you can imagine. Eventually, they're even going to start having brain-machine interfaces, and embedding technology inside their body. That's coming very soon. And so, those are compounding advantages: When you have those kind of advantages, they feed on each other and compound and grow, and the divide between that group and everyone else who doesn't have those advantages just gets wider and wider. And I think we're seeing that more and more. Increasingly, a tiny elite who understand the internet, understand computing, understand software, and understand themselves and how to interface themselves with these things, are tapping into resources and sheer power that in previous areas was reserved for heads of state. I mean, others have observed that the average person with a personal computer connected to the internet has resources, informational resources, that the president of the United States did not have even just 20 or 30 years ago. That's kind of unfathomable. And they're using those resources- they're using them to become even better, even faster, even richer, even more leveraged, to really extend their capabilities and extend their ability to shape their own future, their own destiny. I think that's the main reason the divide is getting worse, is simply the compounding advantages on this side of the divide that aren't available to everyone else. At the same time that technology has this concentrating force, it tends to concentrate power and resources, at the very same time, technology is a democratizing force. It's really this big paradox. You know, think about, I've seen others kind of remark that a billionaire and the average college student are using the same computer. They're using probably a PC or a Mac. That is a remarkable turn of events. They're probably using the same phone. In fact, the student may have a better phone than the billionaire. That has never before happened in history. In all of history, the billionaire, everything that they had would be far superior. Think about the fact that so many online services are free. Social media is largely free. Content is largely free. Google is free. That is an incredibly democratizing force; it's a populist force. Technology is a populist force in the world. But I think there's a limitation on that democratizing trend, which is education. It's education. I mean, this is what I'm providing, what I have to offer, is, "Okay, technically you have access to all these online services, but do you know how to use them? Has someone oriented you? Has someone trained you? Do you have peers and people you know in your life who tell you, 'Hey, I'm using this thing. You should try it,'" right? If you have a question or you encounter a roadblock, is there someone you could reach out to for help? Even something as simple as, I notice in my online course, which I teach on Zoom, the self-confidence to raise your hand, your little digital Zoom hand, and say, "Hey, I have a question. I have something to say." That takes a lot of self-confidence. Some people do that constantly, they're always engaging, always participating, and then the rest of the class is just sitting there passively in silence, right? To me, this is education. It's role models. It's modeling. It is a cultural thing. It's a linguistic thing. Something like personal knowledge management: If you look at Maslow's hierarchy, what we're talking about is like way high up the pyramid, right? It's way up there towards self-actualization. And you only have the privilege of even thinking about this if all the other layers are in place. You're not gonna go think about digital note-taking if you have problems with food or water or safety and security or belonging. Unless all those other levels are in place, that just doesn't make more sense to talk about software. And so I think it's education, it's access, it's democratizing not just the chance, okay, "Oh, just go to this website," but the actual support system that people need to adopt a new behavior in their life.

- When should we start teaching second brain practices?