How curling — that weird Winter Olympics sport — can help you make better decisions

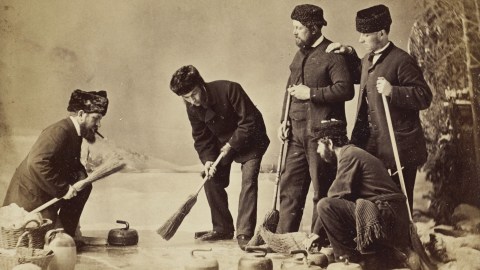

Credit: William Notman / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

- Curling is an odd way for Canadians and Norwegians to spend their idle time, but the game can teach you about life.

- A combination of finesse and urgent communication is required to play it well.

- Curling is a metaphor for life’s decision arcs — after being set in motion, further actions can be taken to alter its course.

Metaphorically speaking, there are parallels to how a decision arc moves and how the stone in the sport of curling moves. In this sweet and beautiful sport, one of those events that reminds us every four years during the Olympics of how Canadians and Norwegians spend their idle time, a thrower gracefully slides across the ice in a low lunge similar to the yoga pose Anjaneyasana. Toward the end of this slide, the player gently nudges a curling stone along its path. The stone looks somewhat like Grandma’s teapot made of granite with a handle mounted on top. It glides toward a bull’s-eye painted below the icy surface. The objective is to get closest to the centermost circle of the bull’s-eye — or, if it is already occupied, to knock out an opponent’s favorably resting stone. The sport is at once elegant and nasty.

To my inexpert mind, the game of curling is won or lost based on the aggregate effect of two offensive actions. The first action is, of course, setting the stone on its initial course across the ice with the right amount of force supplied by the first player on the three-person team. The second action comes from the team’s other two members, who race out in front of the gliding stone, rubbing furiously at the ice in front of it. Collectively, the players yell to one another staccato commands with such force and volume that it brings back the adolescent trauma of my father yelling profanities as I backed a gooseneck trailer up to a crooked gate in the dark.

The decision arc will shift in response to both powerful and subtle forces seeking to change its course.

The secret to the game seems to lie in creating enough heat on the surface of the ice to create a wet surface, reducing friction during the glide while affecting the force and rotation of the stone to bend its trajectory to a more ideal landing spot. The theoretical precepts of these physics, however, are hotly debated by those same Canadians and Norwegians.

Decision arcs work the same way, at least metaphorically. There is a natural trajectory that has already been put into motion. We inherit this first dimension of the decision arc. This inertia is extremely powerful.

A decision arc will have an inherited path that is fueled by inertia. Its future path is determined by the influences upon it, including how the actors exercise their judgment in seeking to direct it.

Then we go to work trying to influence the continuation of the trajectory. The goal is to increase the probability of our success by shaping the arc taken by the stone. We rub vigorously at the ice. Profanity is permitted.