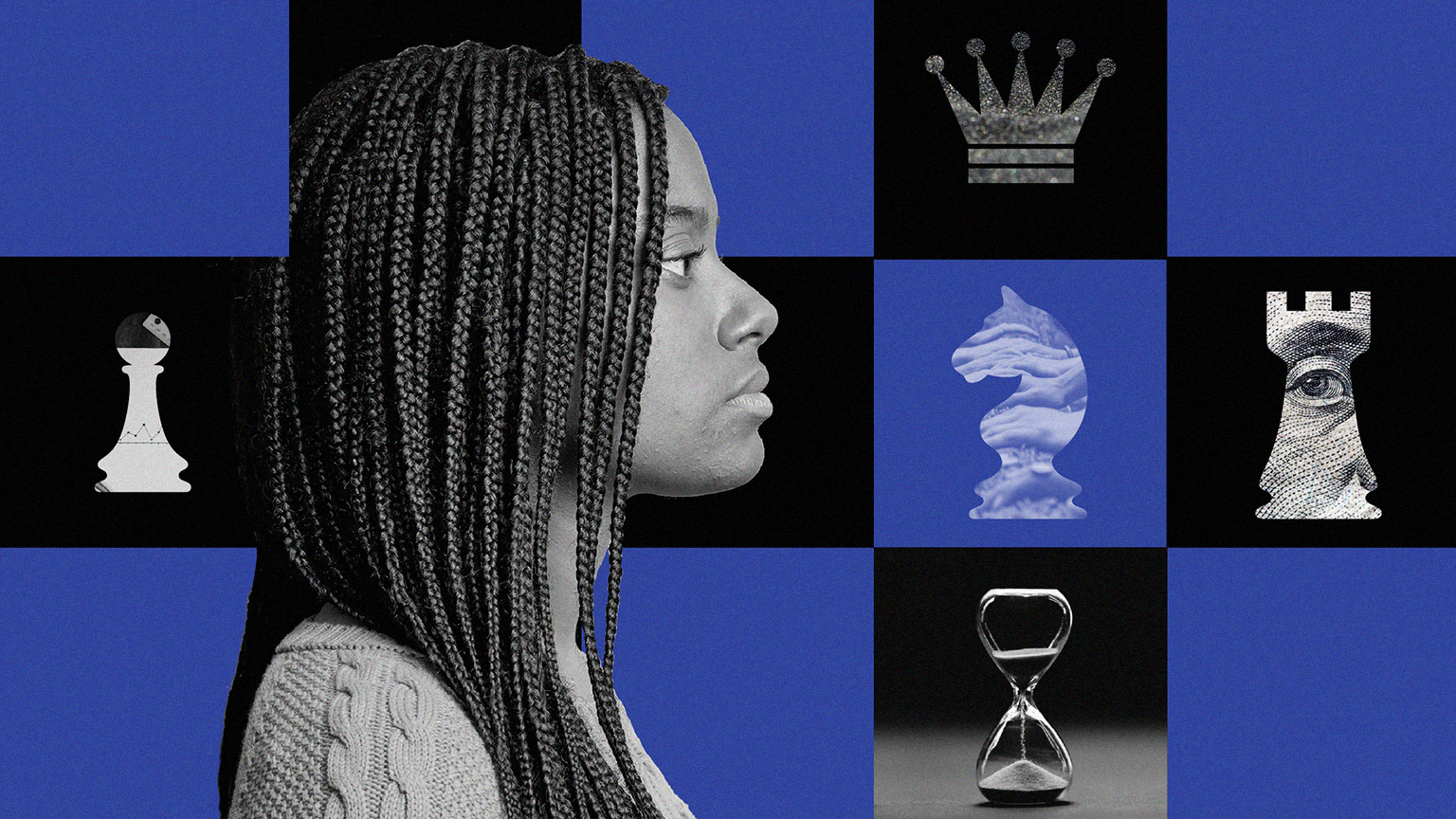

Recognize the “performance paradox” and break free from stagnation at work

Credit: Ranjithsiji / CC BY-SA 4.0 / Wikimedia Commons

- “Chronic performance” — throwing more energy at tasks yet staying at the same level of effectiveness — can have a devastating impact on our lives.

- Hard work doesn’t always lead to better performance.

- The “performance paradox” is the counterintuitive phenomenon that if we want to improve our performance, we have to do something other than just perform.

Early in my career, I was the youngest investment professional at the Sprout Group—then one of the oldest and largest venture capital firms in the world. I loved being exposed to different executive teams, industries, and companies at the leading edge of innovation, and I had the exciting opportunity to serve on boards of directors alongside much more experienced and knowledgeable investors and operators.

But when I think back on those days, what I remember most vividly is the incredible pressure I felt to perform. We regularly sat in meetings listening to startup teams pitch their ventures. The entrepreneurs would describe their solutions for problems in an industry’s supply chain, or pitch a new drug discovery process or an innovation in an enterprise software system. When the entrepreneurs stepped out of the room, we’d take turns voicing our impression of the opportunity. As a very junior professional just starting my career, I didn’t know enough to have a strong conviction about whether an investment was attractive, but I pretended to.

As my colleagues shared their impressions, I would try to decide what to advocate for. I might have liked a startup’s large market opportunity but worried about how undifferentiated the technology seemed—was this value proposition really that different from the other pitches we’d heard that year? Or I might have had mixed feelings about the competitive dynamics or the management team’s experience. When my turn came, I left my conflicting thoughts and uncertainties unspoken to make it appear that all of my thinking pointed in one direction and that I had high confidence in my recommendation. I would pick a side—to engage in due diligence or turn down the opportunity, or to invest or not—and advocate for it with certainty.

I realized that by not sharing some of my thoughts, I was withholding information that could have increased our capacity to make good decisions. This caused me anxiety because I wanted to help our team, but I was handcuffed by my belief that I needed to appear knowledgeable, decisive, and confident of my opinions.

After years of this, I got very good at looking like I knew what I was doing, and I consistently received great performance reviews and bonuses. But inside I felt disingenuous and inauthentic. I was constantly pretending.

Eventually, the chronic stress of these feelings affected my body physically. Under constant pressure, I kept my muscles contracted, so much that, eventually, they lost their ability to relax. It turns out that muscles are malleable, for better or for worse! Mine became shorter and harder, preventing blood from penetrating them and delivering the nutrients needed for proper functioning and healing.

It became painful for me to use my hands—to type, use the computer mouse, drive a car, open doors, even brush my teeth. After seeing many specialists, I was finally diagnosed with a repetitive strain injury called myofascial pain syndrome.

As time went on, my condition grew worse. I met people with the same affliction who could no longer use their hands for more than ten minutes a day, and it terrified me. I was determined to do all I could to heal. But I suspected that what I needed to change was more than just my posture.

Are you always racing to check tasks off a list? Do you spend most of your time trying to minimize mistakes? Do you suppress your uncertainties, impressions, or questions to try to appear like you always know what you’re doing?

Would you rather walk over hot coals than get feedback? These are all signs of chronic performance. While it may seem like minimizing mistakes is a reasonable use of our time or that appearing decisive is a wise career strategy, these habits can have a devastating impact on our skills, confidence, jobs, and personal lives.

Chronic performance could be the reason you might be feeling stagnant in some area of your life. You might be working more hours or putting more effort into tasks, yet you never seem to get ahead. Life feels like a never-ending game of catch-up. That’s chronic performance—throwing more energy at tasks and problems yet staying at the same level of effectiveness.

Most of us go about our days assuming that in order to succeed, we simply need to work hard to get things done. That’s what we’ve been told all our lives. So what’s the problem? Doesn’t hard work lead to better performance? The answer is a paradox—one I call the performance paradox.

Maybe you’re a busy professional trying to learn a difficult new skill, like giving masterful presentations, motivating colleagues, or resolving conflict, yet no matter how much you work at it, you don’t seem to be getting better.

Why does the paradox ensnare so many of us? It’s a seemingly logical response to feeling pressured, overwhelmed, and underwater.

You could be a leader whose team achieves the same results month after month even though you are certain everyone is working hard. Or perhaps you’d like to deepen your relationships with your family, friends, or colleagues, but conversations stay superficial.

The performance paradox is the counterintuitive phenomenon that if we want to improve our performance, we have to do something other than just perform. No matter how hard we work, if we only do things as best as we know how, trying to minimize mistakes, we get stuck at our current levels of understanding, skills, and capabilities.

Too often, the performance paradox tricks us into chronic performance, which leads to stagnation. We get stuck in a hamster wheel in our work, as well as in our relationships, health, hobbies, and any aspect of life. It can feel like we’re doing our best, when in fact we’re missing out on discovering better ways to create, connect, lead, and live.

Why does the paradox ensnare so many of us? It’s a seemingly logical response to feeling pressured, overwhelmed, and underwater. We think the answer is to just work harder and faster, but the way to improve our performance is not to spend more time performing. It is to do something else that is a lot more rewarding and, ultimately, productive.