Ask Ethan #47: Do Science and Religion have to be at odds?

And if not, how do you reason with those who believe they are?

“Ignorance is hardly unusual, Miss Davar. The longer I live, the more I come to realize that it is the natural state of the human mind. There are many who will strive to defend its sanctity and then expect you to be impressed with their efforts.” –Brandon Sanderson

Every week, you have your opportunity to send in your questions and suggestions for a column here on Starts With A Bang, and at the end of the week, I’ll choose the ones that stands out the most to me for our Ask Ethan column. No topics are off-limits, but I’ve never had a question, suggestion, or in general a submission like the one I received from Jonathan Hasey, who shared the following about himself:

As a young person, I leaned towards a young-earth creationism… I’ve gradually drifted into an acceptance of evolutionary biology. […] [I] learned that there can be no conflict between the truth found in different domains of knowledge — if there is a conflict, it demonstrates that we’re missing something.

I’ve synopsized his submission for brevity, but included his entire note at the end for anyone who’s curious. This may be a can-of-worms and my response may offend a great many of you, but you know the old saying, “nothing risked, nothing gained.” Let’s dive on in.

When we first arrive in this world, we’re confronted with a tremendous amount of new stimuli: a whole Universe’s worth of experience. And, as anyone who’s ever been a child or interacted with a child can tell you, that leads to questions about everything. “What’s that?” “Why?” “Why?” And so on. And even the most knowledgable among us will quickly run into a situation where we run out of definitive answers, at least as far as we know them.

The big question, then, becomes how do you proceed when you find yourself in that situation?

Do you seek out someone or something you deem to be an authority, and follow whatever it is that authoritative source has to say?

Do you seek out all the various possibilities, considering their ramifications and implications, and then choose from among them?

Or, perhaps, do you seek out a way to test the various ideas, and let the evidence determine where the truth lies?

At various points and for various questions in our lives, we all make use of each of these approaches, for historical reasons, for reasons of carefulness and accuracy, for personal reasons, and for expedience as well. But that doesn’t mean — as Jonathan stated — that anything needs to be in conflict.

Take evolution, for example. Or, more accurately, take the DNA that encodes an organism’s genetic makeup. Thousands of years ago, we could examine and know how the various plants, animals and fungi were similar and different from one another on a macroscopic level, but not why they were so. We didn’t have sufficient knowledge to know which forms of life were closely related, to others, whether all life had a common origin, or whether the microscopic mechanisms regulating these organisms were unique or not. Those are the kinds of questions that lend themselves to being answered by a scientific process: you inquire, you gather information, you come up with ideas to test and then you perform those critical tests. And as a result, your knowledge increases.

At the current point in time, we know that the genetic code of living creatures is the primary determinant — even starting out from a single cell — of what they will grow up to be. The changes that occur in that DNA from generation-to-generation is what allows organisms to change and vary in their form over time, and the pressures of a changing, limited environment with finite resources is what enables some organisms to survive, thrive and reproduce, while the others are selected against.

Now, I didn’t do that research myself; in fact, no one person did. Scientific knowledge is built person-by-person, observation-by-observation, experiment-by-experiment, and generation-by-generation. Science is both a process — an additive process where all the data ever scrupulously gathered is cumulative — and also a body of knowledge. The most successful scientific theories explain the widest variety of phenomena with the fewest parameters and assumptions. They have the greatest predictive and post-dictive powers, and the largest range of applicability.

And the scientific truths of the Universe, or what we can learn simply by asking the matter and energy around us questions about itself, are truths that are there for everyone to share in.

“When you make the finding yourself — even if you’re the last person on Earth to see the light — you’ll never forget it.” -Carl Sagan

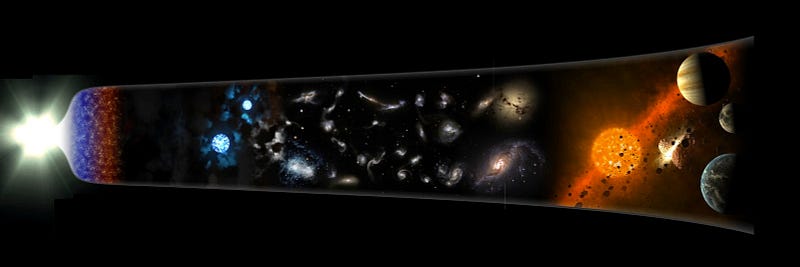

Image credit: NASA.

All that said, science is limited. Science is never 100% positive of its conclusions; there’s always room for doubt, improvement, and refinement. Despite constant predictions that science is about to end, it always leads us to even deeper and more fundamental questions, and — eventually, if the solution is knowable — deeper truths about the Universe itself. There’s an outstanding chance that we know today, to the best of our scientific ability, will be regarded as only an approximation to what we’ll know a century from now.

Newtonian gravity is only an approximation to Einstein’s General Relativity, and it’s strongly suspected that a fully quantum theory of gravity will someday supersede Einstein’s theory on the smallest scales and in the largest gravitational fields. The idea that every component of matter could be reduced to indivisible particles was thrown on its head when quantum mechanics showed that these “particles” didn’t always behave like we thought particles should, and since then quantum mechanics has been superseded by the even more powerful quantum field theory. Yet no one thinks that’s the end of what we’ll ever know, either.

We learn more by asking more questions, and by revising our best answers based on the new knowledge gained. When we say that science is both a process and a body of knowledge, this is what we mean.

“I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.” -Galileo Galilei

Image credit: © 2014 Biography / A&E Television Networks, LLC.

And it’s for everyone. Whether you’re an atheist, a deist or a theist, the physical Universe is the same for us all, and we all can share in the joys, wonders and benefits of knowledge that our best scientific understanding brings us.

That doesn’t necessarily invalidate our history, culture, or beliefs. I am quite positive that my own beliefs about where the Universe originated from are not shared by the vast majority of those of you reading this, but perhaps we can agree that as we continue to learn more about the fundamental rules that underpin this Universe, we can come to better understand the truths that underlie our very existence.

As far as our moralities go — our senses of right-and-wrong, of how to behave and treat one another, of how to live well and be happy — I think we can all agree that’s something worth spending time on for ourselves, and that’s something we all need to cultivate from within as individuals. If you can grow that through your family, or your religion, or your community, or your atheism, or your yoga practice, or simply through your own internal meditation, I think you’re doing it right.

No matter what, I want to thank you for being open to considering perspectives other than your own as also being at least partially valid, as well as being as valuable to others as your own perspective is to you yourself. It’s my great hope, however, that the value of science — that an awareness and an appreciation of what the scientific enterprise is and how it benefits us all — is something we can all share in.

And with that said, I’d like to share with you Jonathan’s letter in full.

I just wanted to express my appreciation for your blog. I recently began reading it (a couple of weeks ago) via Medium, and you should know that in just a few articles, you have managed to significantly impact my understanding of the universe.

As a young person, I leaned towards a young-earth creationism, which I now think only maintains its existence as an overreaction to that evolutionary philosophy which suggests that because evolution is true, the God of the Bible must not be real. I’ve gradually drifted into an acceptance of evolutionary biology, especially once I became Catholic and learned that there can be no conflict between the truth found in different domains of knowledge — if there is a conflict, it demonstrates that we’re missing something.

Reading your blog, I have finally been able to give myself permission to explicitly accept the theory of evolution, and that is because you

a) are very good at explaining big concepts in simple terms, and

b) in teaching about the universe, you do it in a way that remains open to different philosophical perspectives (and thus not an attack on religious beliefs).

A wonderful example of that is your article addressed to creationists, which, while obviously criticizing their specific beliefs about creation, manages to do it in a respectful, even friendly way. You tend to focus on how science makes things beautiful, and beauty is the best way to reach the heart.

And, I was also suspicious of global warming claims, mostly because of its association with noisy politicians who I suspect have ulterior motives. Just in reading your one article on the subject — today! — I have moved into the “believer” camp, while still remaining suspicious of the noisy politicians.

So, thank you!

Thank you, Jonathan, and thank you to everyone who’s ever spoken to me about their varied beliefs and experiences, as it’s helped me understand what not mere tolerance, but acceptance can truly accomplish. We don’t have to be identical to find common ground, and to use what we know to the best of our ability to build a better world for us all. We just have to choose to value it, and maybe, just maybe, that’s something we can all agree on.

And thank you for a note that I suppose was neither a question or a suggestion, and if you have one, go ahead and submit it here. The next Ask Ethan column could be yours!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!