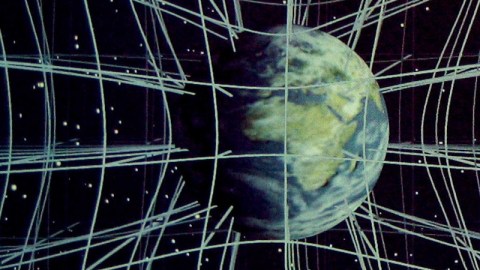

Ask Ethan: How Can We Measure The Curvature Of Spacetime?

It’s been over 100 years since Einstein, and over 300 since Newton. We’ve still got a long way to go.

From measuring how objects fall on Earth to observing the motion of the Moon and planets, the same law of gravity governs the entire Universe. From Galileo to Newton to Einstein, our understanding of the most universal force of all still has some major holes in it. It’s the only force without a quantum description. The fundamental constant governing gravitation, G, is so poorly known that many find it embarrassing. And the curvature of the fabric of spacetime itself went unmeasured for a century after Einstein put forth the theory of General Relativity. But much of that has the potential to change dramatically, as our Patreon supporter Nick Delroy realized, asking:

Can you please explain to us how awesome this is, and what you hope the future holds for gravity measurement. The instrument is obviously localized but my imagination can’t stop coming up with applications for this.

The big news he’s excited about, of course, is a new experimental technique that measured the curvature of spacetime due to gravity for the first time.

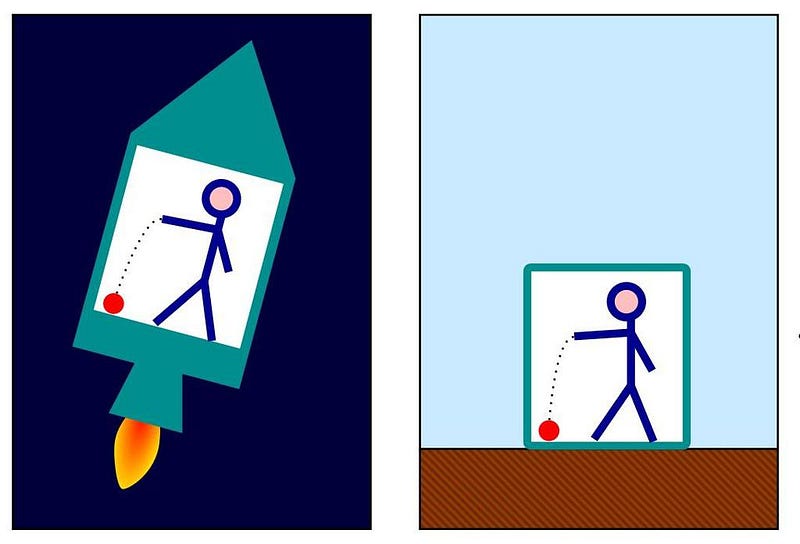

Think about how you might design an experiment to measure the strength of the gravitational force at any location in space. Your first instinct might be something simple and straightforward: take an object at rest, release it so it’s in free-fall, and observe how it accelerates.

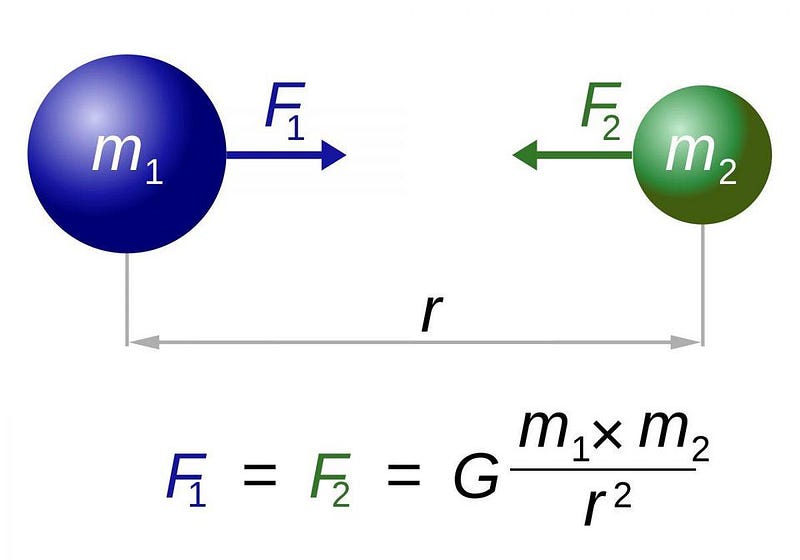

By measuring the change in position over time, you can reconstruct what the acceleration at this location must be. If you know the rules governing the gravitational force — i.e., you have the correct law of physics, like Newton’s or Einstein’s theories — you can use this information to determine even more information. At every point, you can infer the force of gravity or the amount of spacetime curvature. Beyond that, if you know additional information (like the relevant matter distribution), you can even infer G, the gravitational constant of the Universe.

This simple approach was the first one taken to investigate the nature of gravity. Building on the work of others, Galileo determined the gravitational acceleration at Earth’s surface. Decades before Newton put forth his law of universal gravitation, Italian scientists Francesco Grimaldi and Giovanni Riccioli made the first calculations of the gravitational constant, G.

But experiments like this, as valuable as they are, are limited. They can only give you information about gravitation along one dimension: towards the center of the Earth. Acceleration is based on either the sum of all the net forces (Newton) acting on an object, or the net curvature of spacetime (Einstein) at one particular location in the Universe. Since you’re observing an object in free-fall, you’re only getting a simplistic picture.

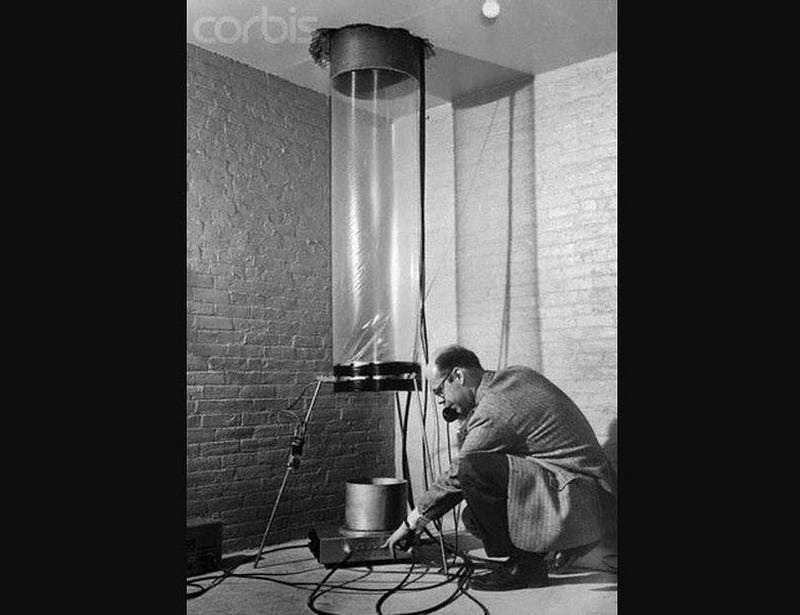

Thankfully, there’s a way to get a multidimensional picture as well: perform an experiment that’s sensitive to changes in the gravitational field/potential as an object changes its position. This was first accomplished, experimentally, in the 1950s by the Pound-Rebka experiment.

What the experiment did was cause a nuclear emission at a low elevation, and note that the corresponding nuclear absorption didn’t occur at a higher elevation, presumably due to gravitational redshift, as predicted by Einstein. Yet if you gave the low-elevation emitter a positive boost to its speed, through attaching it to a speaker cone, that extra energy would balance the loss of energy that traveling upwards in a gravitational field extracted. As a result, the arriving photon has the right energy, and absorption occurs. This was one of the classical tests of General Relativity, confirming Einstein where his theory’s predictions departed from Newton’s.

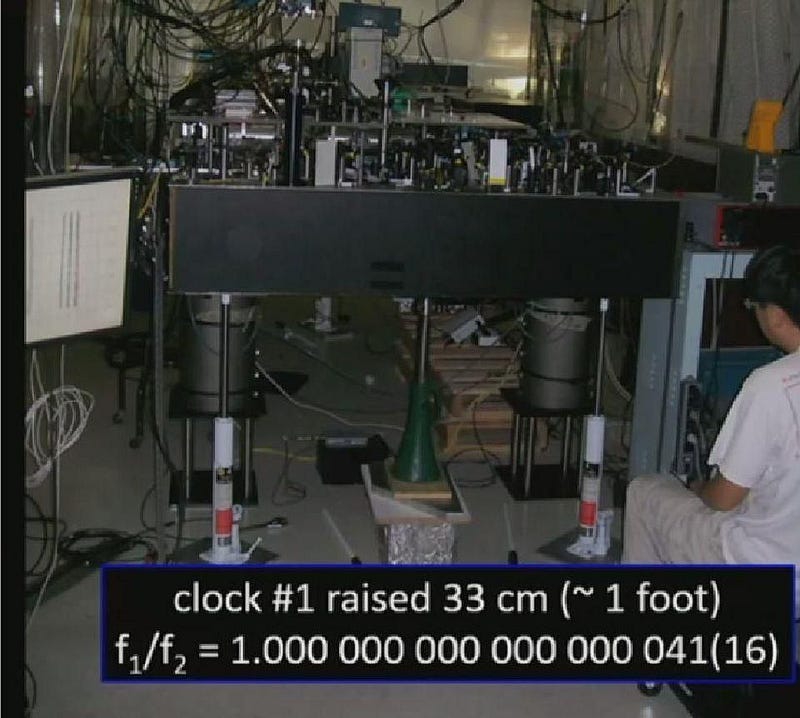

We can do even better than the Pound-Rebka experiment today, by using the technology of atomic clocks. These clocks are the best timekeepers in the Universe, having surpassed the best natural clocks — pulsars — decades ago. Now capable of monitoring time differences to some 18 significant features between clocks, Nobel Laureate David Wineland led a team that demonstrated that raising an atomic clock by barely a foot (about 33 cm in the experiment) above another one caused a measurable frequency shift in what the clock registered as a second.

If we were to take these two clocks to any location on Earth, and adjust the heights as we saw fit, we could understand how the gravitational field changes as a function of elevation. Not only can we measure gravitational acceleration, but the changes in acceleration as we move away from Earth’s surface.

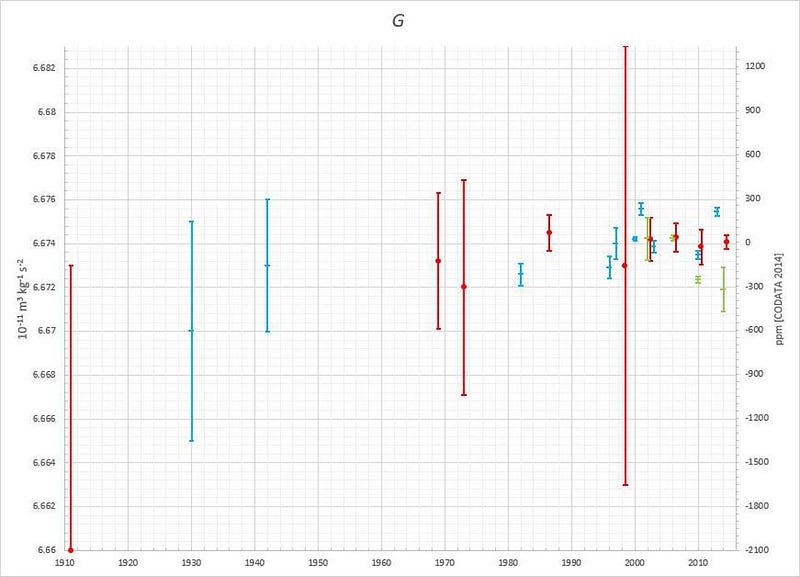

But even these achievements cannot map out the true curvature of space. That next step wouldn’t be achieved until 2015: exactly 100 years after Einstein first put forth his theory of General Relativity. In addition, there was another problem that has cropped up in the interim, which is the fact that various methods of measuring the gravitational constant, G, appear to give different answers.

Three different experimental techniques have been used to determine G: torsion balances, torsion pendulums, and atom interferometry experiments. Over the past 15 years, measured values of the gravitational constant have ranged from as high as 6.6757 × 10–11 N/kg2⋅m2 to as low as 6.6719 × 10–11 N/kg2⋅m2. This difference of 0.05%, for a fundamental constant, makes it one of the most poorly-determined constants in all of nature.

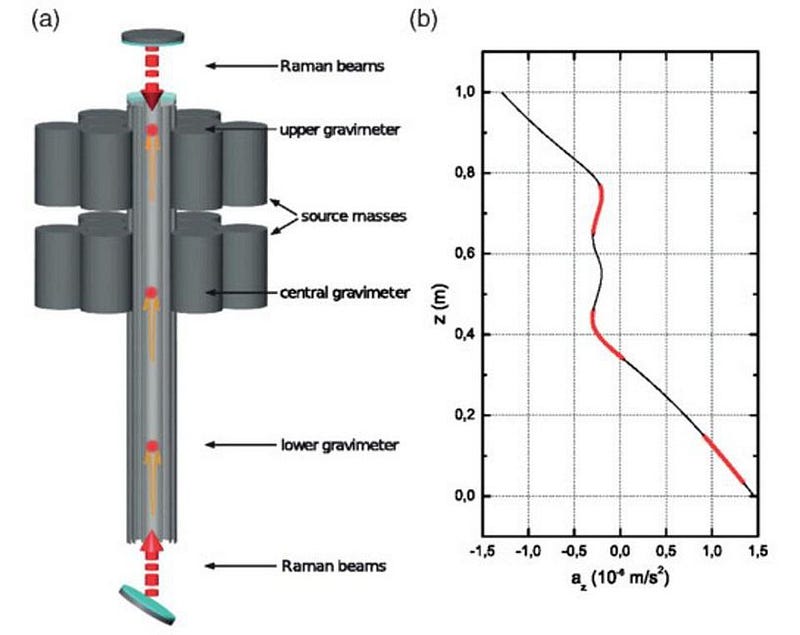

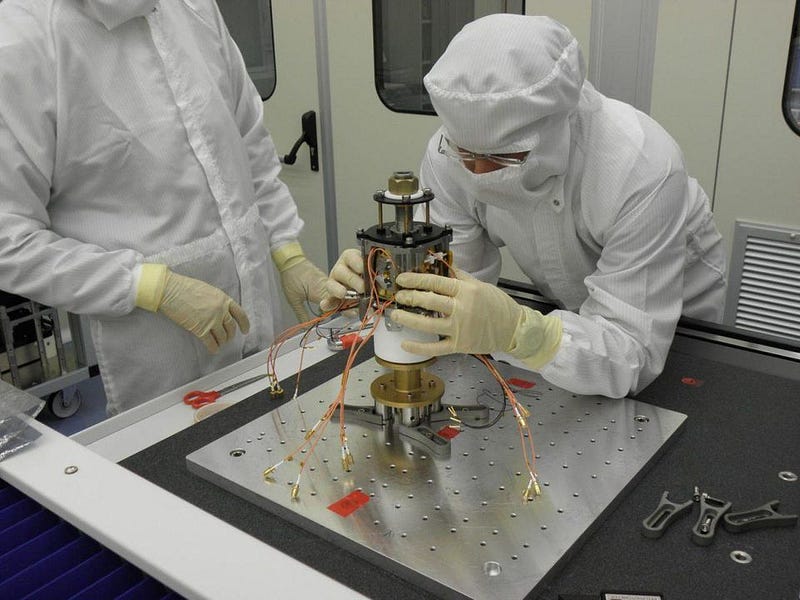

But that’s where the new study, first published in 2015 but refined many times over the past four years, comes in. A team of physicists, working in Europe, were able to conjugate three atom interferometers simultaneously. Instead of using just two locations at different heights, they were able to get the mutual differences between three different heights at a single location on the surface, which enables you to not simply get a single difference, or even the gradient of the gravitational field, but the change in the gradient as a function of distance.

When you explore how the gravitational field changes as a function of distance, you can understand the shape of the change in spacetime curvature. When you measure the gravitational acceleration in a single location, you’re sensitive to everything around you, including what’s underground and how it’s moving. Measuring the gradient of the field is more informative than just a single value; measuring how that gradient changes gives you even more information.

That’s what makes this new technique so powerful. We’re not simply going to a single location and finding out what the gravitational force is. Nor are we going to a location and finding out what the force is and how that force is changing with elevation. Instead, we’re determining the gravitational force, how it changes with elevation, and how the change in the force is changing with elevation.

“Big deal,” you might say, “we already know the laws of physics. We know what those laws predict. Why should I care that we’re measuring something that confirms to slightly better accuracy what we’ve known should be true all along?”

Well, there are multiple reasons. One is that making multiple measurements of the field gradient simultaneously allows you to measure G between multiple locations that eliminates a source of error: the error induced when you move the apparatus. By making three measurements, rather than two, simultaneously, you get three differences (between 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 1 and 3) rather than just 1 (between 1 and 2).

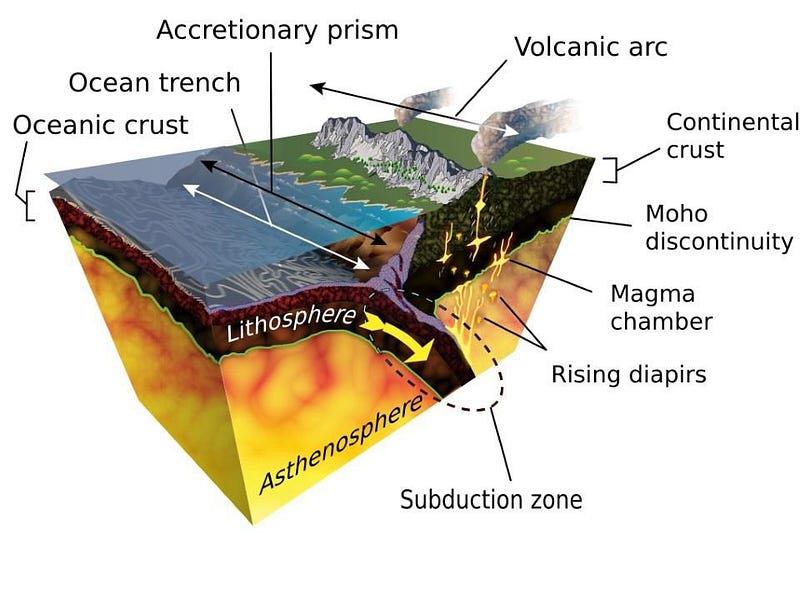

But another reason that’s perhaps even more important is to better understand the gravitational pull of the objects we’re measuring. The idea that we know the rules governing gravity is true, but we only know what the gravitational force should be if we know the magnitude and distribution of all the masses that are relevant to our measurement. The Earth, for example, is not a uniform structure at all. There are fluctuations in the gravitational strength we experience everywhere we go, dependent on factors like:

- the density of the crust beneath your feet,

- the location of the crust-mantle boundary,

- the extent of isostatic compensation that takes place at that boundary,

- the presence or absence of oil reservoirs or other density-varying deposits underground,

and so on. If we can implement this technique of three-atom interferometry wherever we like on Earth, we can better understand our planet’s interior simply by making measurements at the surface.

In the future, it may be possible to extend this technique to measure the curvature of spacetime not just on Earth, but on any worlds we can put a lander on. This includes other planets, moons, asteroids and more. If we want to do asteroid mining, this could be the ultimate prospecting tool. We could improve our geodesy experiments significantly, and improve our ability to monitor the planet. We could better track internal changes in magma chambers, as just one example. If we applied this technology to upcoming spacecrafts, it could even help correct for Newtonian noise in next-generation gravitational wave observatories like LISA or beyond.

The Universe is not simply made of point masses, but of complex, intricate objects. If we ever hope to tease out the most sensitive signals of all and learn the details that elude us today, we need to become more precise than ever. Thanks to three-atom interferometry, we can, for the first time, directly measure the curvature of space.

Understanding the Earth’s interior better than ever is the first thing we’re going to gain, but that’s just the beginning. Scientific discovery isn’t the end of the game; it’s the starting point for new applications and novel technologies. Come back in a few years; you might be surprised at what becomes possible based on what we’re learning for the first time today.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.