Ask Ethan: Why Can’t We Feel Earth Flying Through Space?

Our motion through space is undeniable. So why can’t we feel it?

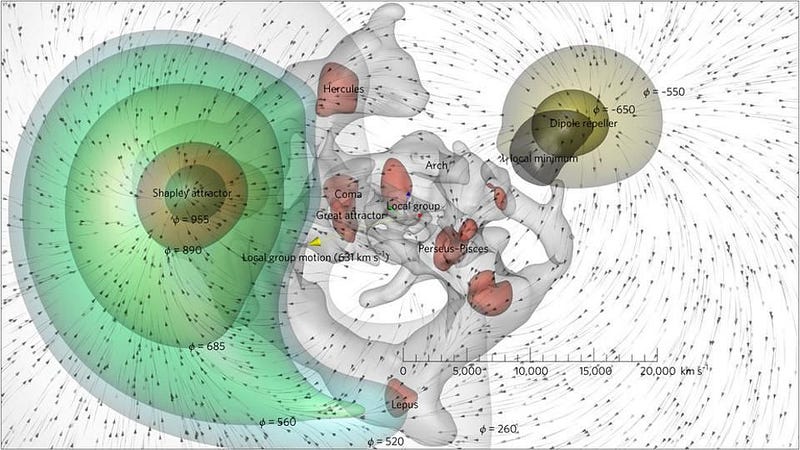

Our planet isn’t the stationary place we feel it to be beneath our feet, but rather moves in an incredibly complex fashion through the Universe. We rotate on our axis once every 24 hours, revolve around the Sun once per year, while the entire Solar System orbits at 220 km/s around the Milky Way, which accelerates towards Andromeda in the Local Group, which itself moves relative to the radiation left over from the Big Bang. That’s a lot of cosmic motion! And yet, we cannot feel it at all. This troubles many, including reader Annie Bennett, who asks:

I desperately need your help! Please help me explain to my husband why you can’t feel earth flying through space!

There’s a simple reason why we cannot feel it in our bodies, but it won’t be intuitive to anyone who’s used to their experiences here on Earth.

If you’re in a car that moves at 15 miles per hour (mph) and you stick your limbs out the window, you’ll feel the wind blow mildly against it. It’s true that the faster you go, the greater the force you’ll feel, but the way that your hand or foot feels the force isn’t necessarily intuitive. If you speed up to moving at 30 mph, the force on your appendage will be four times what it was at 15 mph; if you speed up to 60 mph, that force escalates to sixteen times what it was at 15 mph.

But that force only exists because your hand, physically, is moving at a relative speed to the air molecules it’s colliding with. If, instead, you had the car windows closed, your hand wouldn’t feel any force at all. And that’s because the air inside the car is stationary relative to your body. It’s only when two objects are in relative motion to one another that you can feel a force.

When the Earth orbits the Sun, or when the Solar System orbits the galaxy, or when our galaxy moves relative to the other galaxies in our Local Group, or when the Local Group moves relative to the rest of the Universe, there’s no effect on our bodies that we’re capable of feeling.

There’s no force sensor we can apply in order to detect the effects of this motion for a simple reason: everything that exerts a force on our bodies, causing us to accelerate, is also exerting a proportional force on the Earth, causing it to accelerate at the exact same rate. Just like you cannot feel yourself in motion in a smoothly-riding car with the windows rolled up, you cannot feel the Earth moving through the Universe so long as you, too, are bound to planet Earth. This applies to any scale you can conceive of, from Solar System dynamics all the way to scales of the entire Universe.

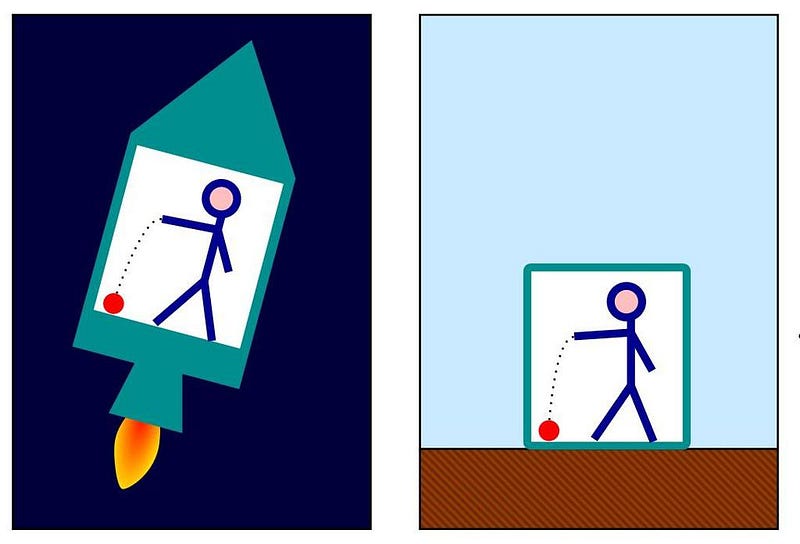

In fact, the story goes even deeper than that, as Einstein first intuited more than 100 years ago. Calling it “his happiest thought,” he realized that any change in an object’s motion would appear to be an acceleration, and that all forms of constant acceleration — including gravitation — would be indistinguishable from one another.

We now call this Einstein’s equivalence principle, and it tells us that any accelerated reference frame cannot have its cause of acceleration determined by an object that’s a part of the internal system. In other words, if you’re a part of the Earth (and sorry, Annie, you and your husband both are) and the Earth is accelerating, then you’ll accelerate too, and you won’t be able to feel the effects of any of the different causes.

This was first realized by Galileo, who understood that a ball dropped from the Leaning Tower of Pisa would fall straight down, rather than lag behind as the Earth rotated, because the Earth’s atmosphere moved along with our planet.

This phenomenon would hold true even if you weren’t on Earth! If you were in space — on the International Space Station, for example — you would absolutely be accelerating due to the influence of everything moving you through the Universe. The Earth tugs on you; the Sun and planets pull on you; the rest of the galaxy and Universe exert a gravitational force on you, too.

Those forces cause you to accelerate. But those same forces also cause all the objects in your environment, including the other astronauts with you, inanimate objects (like fruit), and the space station itself, to accelerate at the same rate as you. You’re in what you experience as “free-fall,” and so are all the other objects there. Relative to your environment, there’s no net force, and hence, no discernible acceleration.

But there are some exceptions that you can detect, although it’s doubtful that your body is sensitive enough. There are forces we experience from the fact that the Earth is a large three-dimensional object, and we’re located at just one point on its surface. Relative to the Earth, we experience some forces somewhat differently from how the Earth, overall, experiences it.

One such exception is tidal forces. You, yourself, are a three-dimensional object. Your feet, on the ground, are slightly closer to the center of the Earth than your head, meaning that the gravitational force from the Earth is slightly greater on your feet. This might not be significant enough for you to notice, but you can design an experiment that is sensitive enough to the tiny differences in the gravitational force. The first one to see it was the Pound-Rebka experiment, which was one of the classical tests of Einstein’s theory of gravity, verifying it spectacularly.

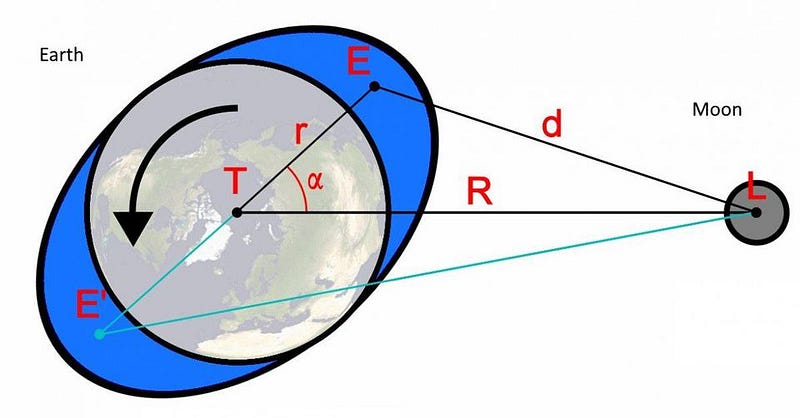

Another is the effect of the tides on Earth itself. The Earth spins, and the Moon tugs on both the crust of the Earth and the oceans surrounding it. As the Earth rotates, the force from the Moon changes on each individual point, causing the oceans to bulge.

Although you, as an individual person, aren’t sensitive enough to detect the force changes, you can easily experience the tides going in and out, as the Earth spins on its axis. The fact that we have two ocean bulges, and that the Earth spins once a day, means that we get two low tides and two high tides daily. You may not be able to feel the tidal forces in your own body, but you can clearly experience its effects.

Finally, the fact that the Earth itself rotates results in a special type of force experienced by everything on its surface: the Coriolis force. Because the Earth is rotating relative to a fixed location (i.e., about its axis), points along its surface at different latitudes will experience a slight force that causes an additional rotatation.

The maximum amount of force would be experienced by an object at either the North or South Pole, which would cause it to experience an extra 360 degree rotation over an object that weren’t on Earth. But the two different hemispheres experience rotation in opposite directions: the North Pole feels a counterclockwise rotation while the South Pole feels a clockwise one. For someone at the equator, the force drops to zero, and someone at intermediate latitudes gets only a partial rotation over the course of a day.

The first time this experiment was done was in dramatic fashion in France by Léon Foucault, who performed his 1851 experiment by attaching an enormous weight via a long string to the ceiling of the Pantheon in Paris, France. After letting it go in a straight line, it was monitored over the course of a day, swinging and swinging. As the hours ticked by, it became clear that the pendulum wasn’t moving in a simple back-and-forth motion, but rotated relative to the rest of the Pantheon.

This was indisputable proof that the Earth itself was rotating, that the Coriolis force was real, and that the predictions of a spinning Earth were, in fact, borne out by a direct, easily visible experiment.

As a human being, the force sensors on our bodies are primitive, and only work over extremely short terms. It takes the enormous cumulative effects that only occur over the course of a day to be able to experience the rotation of the Earth, or precision measurements that go far beyond the capabilities of our body, to detect Earth’s motion.

But this motion is real, and the reason you can’t feel it isn’t because we aren’t moving, but rather because your human body is in constant, uniform motion with respect to the Earth itself. If something exerted a differential force on you from the Earth, you’d feel it immediately. But in the absence of that, you’ll need a much more sensitive instrument than a mere human body. In a nutshell, that’s a huge part of what science is all about: figuring out ways beyond our mere obvious senses to explore and learn about the Universe. The Earth does move, and a Foucault pendulum is how you can see its effects for yourself!

Send in your Ask Ethan submissions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.