Messier Monday: A Globular from the Galactic Center, M9

Peeking out through the galaxy’s dust, this ancient relic has plenty to offer if you know where to look!

“When someone demands blind obedience, you’d be a fool not to peek.”

–Jim Fiebig

Imagine that you were a tiny, overdense region of space when the Universe was first beginning. If you were too small in terms of size, excess energy would stream out, forcing you back down to average. If you were too large in terms of size, you’d have to wait until the Universe was old enough for the speed of gravity to tell you to start collapsing. But if you look at the cosmic microwave background — or the leftover glow from the Big Bang — there’s a minimum size to the density fluctuations that survive.

The “smallest large-magnitude fluctuations” that make it will collapse and grow into the first structures in the Universe: gravitationally bound clumps of dark matter and gas that weigh in at around a few hundred-thousand times the mass of our Sun. Perhaps coincidentally, the most numerous structures in the Universe are around that same mass: the globular clusters, which number in the hundreds or even thousands (or tens of thousands) for every galaxy in the Universe. Most of them wind up orbiting in a galaxy’s halo, and a full 29 of them are represented in the Messier catalogue, all but one of which is in our own galaxy.

Many of these globulars may be as old as or even older than our galaxy itself, and today’s object — Messier 9 — formed no later than 12 billion years ago. Located just 5,500 light-years from the galactic center itself, this clump of stars weighs in at nearly half a million Suns, and is visible with just a pair of binoculars or a small telescope if you know where to look. Even on a Moon-filled summer night like tonight, it can provide you with spectacular sights.

Here’s how to find it.

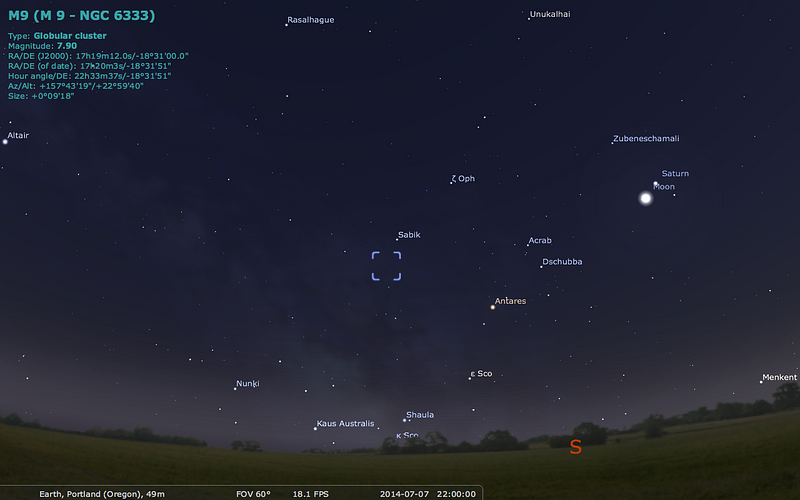

After the Sun goes down tonight, you’ll notice a bright, waxing Moon in the southern portion of the sky, along with a bright yellow dot very close by: that’s the planet Saturn. Further to the south and east, the bright orange giant, Antares, shines prominently. Moving further towards the east and a little bit north, you’ll find the bright blue star Sabik, the second brightest star in the constellation of Ophiuchus. (Interestingly enough, if you lived on the planet Uranus, Sabik would be your pole star!)

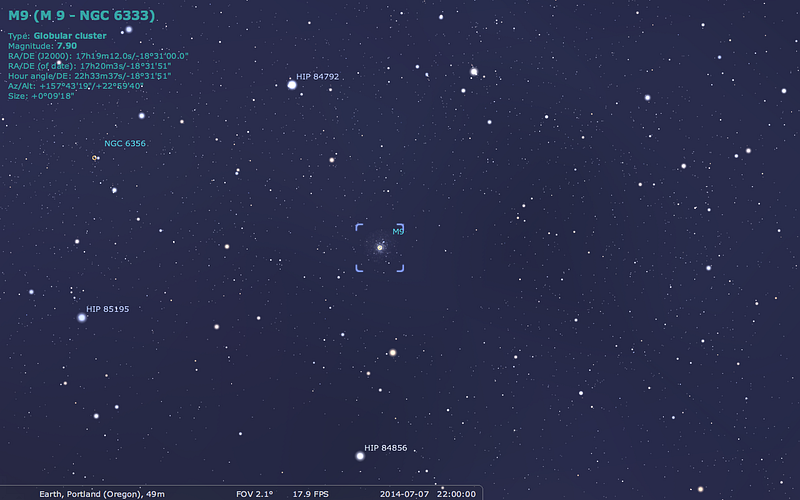

If you’re looking for Messier 9, Sabik is a great place to start. South of Sabik (closer to the horizon, if you’re looking at it after sunset), you’ll find two other prominent naked-eye stars that appear to make an “arc” facing away from Antares: ξ Ophiuchi and the brighter θ Ophiuchi.

It looks like this “arc” would be symmetric if only there were a prominent fourth star in between Sabik and ξ Ophiuchi, but there are no naked eye stars to be found. Instead, point your binoculars (or your low-power telescope) at the area where you want that fourth star to be!

Instead, in between the two bright Hipparcos stars (labeled top and bottom, above), you’ll find a faint, fuzzy ball that appears to fade out as you move away from the center. That’s Messier 9, one of the original discoveries of Charles Messier in 1764 and described by him as:

Nebula, without star, in the right leg of Ophiuchus; it is round & its light is faint.

Indeed, with the best equipment of 250 years ago, Messier was unable to see the individual stars making up an object like this.

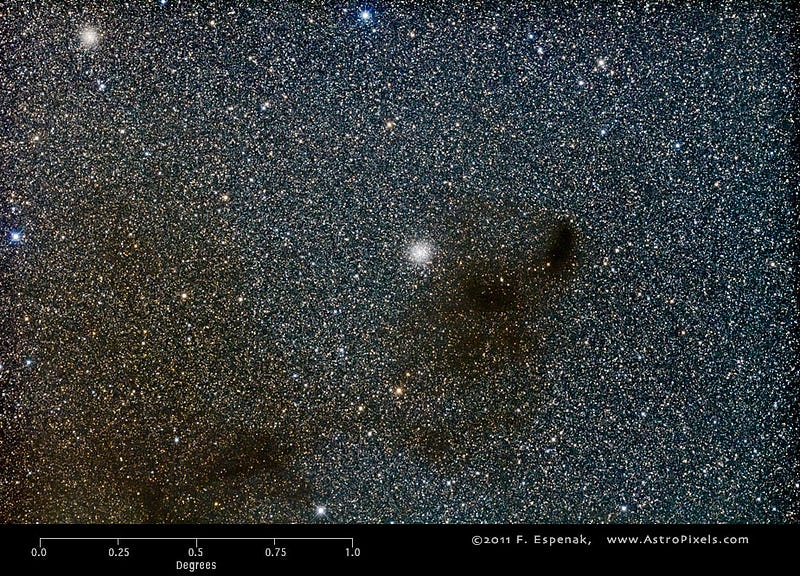

But it isn’t because there aren’t stars in it; it’s because the stars in this object are 25,000 light-years away, about six times as far away as the most distant individual star visible to unaided human eyesight. We’re actually very lucky when it comes to this object, because if it were positioned only a quarter of a degree west/southwest from where it is right now, it would appear obscured by one of the Milky Way’s prominent dust lanes. As a result, it would have been rendered invisible to Messier (and to us, as well) in visible wavelengths of light!

At first glance, the cluster might look a little bit oval-shaped, but that isn’t because it is intrinsically oval-shaped, it isn’t at all. Instead, the dust from the plane of the Milky Way slightly darkens one side of this collection of stars, making it appear as though it’s larger on one side than the other.

If we look, instead of in visible light, in the infrared portion of the spectrum (which is transparent to dust), the symmetric nature of this cluster becomes more apparent.

The stars in this cluster are some of the oldest in our local neck of the Universe, too. Our Sun is relatively rich in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, mostly because our galaxy burned through so many generations of stars prior to our own, and we formed in an area that was heavily enriched with the atoms recycled from those generations.

But the stars in Messier 9? They contain only 1.7% of the heavy elements found in our Sun, telling us that these stars are old. This is further confirmed by the fact that — with the exception of blue straggler stars, or stars formed recently from the merger of older stars — there are no O, B, A, or even bright F-class stars in Messier 9.

There are plenty of red giants in there, however, which is something the Sun will become for hundreds of millions of years after it’s through burning its core hydrogen. For a long time, it was known that this cluster is incredibly close to the galactic center, and was thought to have slightly over 100,000 stars in it. (Wikipedia’s still out of date, for those of your checking.)

But then, two years ago, Hubble imaged it.

Yes, it is very close to the galactic center, but Hubble was able to image the inner core of this cluster, finding 250,000 individual stars in the inner region of the cluster alone! This is a class VIII cluster, a little on the less-dense end of the intermediate range, meaning that there is a noticeable central concentration here, but the outer regions are relatively rich in stars as well, and that the cluster extends for quite a distance — around 45 light-years — from the center.

A zoom into the cluster shows just how close to the galactic center it really is.

As a special treat, I’ve gone and taken the Hubble image and cut into it at full-resolution, to give you a scroll-through view of the innermost region at the highest resolution available. Hold your breath and take a look, and know that from the outskirts of the cluster, this is the brilliance of what your night sky would look like!

And there’s simply no way to top that, so that will bring us to the end of another Messier Monday! Including today, we’ve taken on the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back next week for another spectacular view of the deep-sky wonders of our Universe, only here and only on Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs.