Messier Monday: Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, M93

How the last open cluster ever discovered by Messier himself still holds some amazing secrets and wonder more than 200 years after its discovery.

“The journey is difficult, immense. We will travel as far as we can, but we cannot in one lifetime see all that we would like to see or to learn all that we hunger to know.” -Loren Eiseley

Welcome back to another Messier Monday here on Starts With A Bang! Since Galileo first turned a telescope upwards towards the heavens more than 400 years ago, we’ve recognized that there’s an entire Universe out there to explore beyond what’s visible to our naked eye. By the late 18th Century, Charles Messier set out to catalogue all the deep-sky objects — the extended, permanent fixtures in the night sky — visible with the equipment of his time. The idea was that comet-hunters would be able to reference his catalogue to prevent mistaking a permanent object for a transient comet, but what we wound up with was so much better.

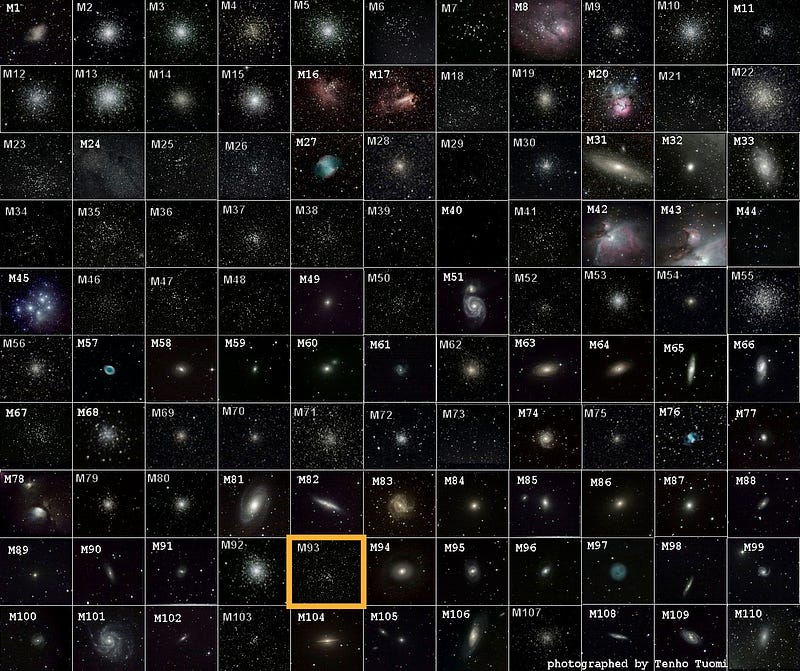

What he instead compiled, with the help of his assistant, Pierre Méchain, was a catalogue of 110 deep-sky curiosities: the brightest and most interesting objects visible from most inhabited locations on Earth. (With some apologies to southern hemisphere dwellers.) Each Monday, we take an in-depth look at one of these, and today’s object is a good one even when there’s a nearly full Moon polluting your winter skies: Messier 93, the last open star cluster discovered by Messier himself. Here’s how to find it.

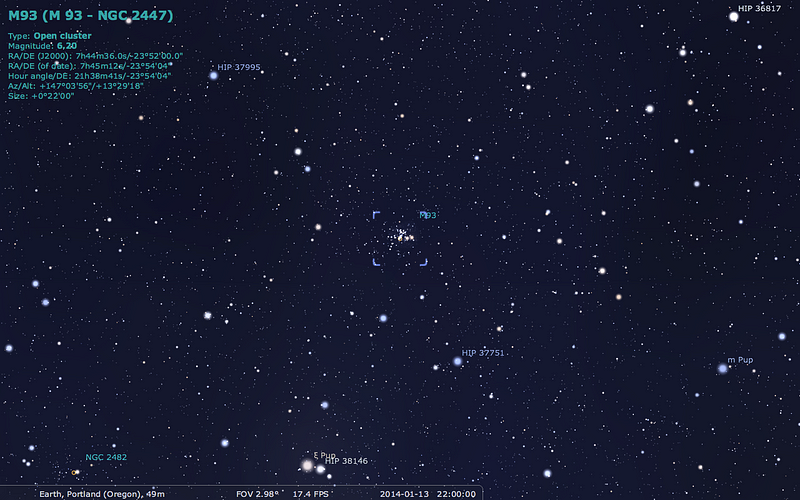

After sunset tonight, a nearly full Moon rides above the constellation Orion, which is trailed by the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius, towards the east. Rising a bit later in the evening, the stars Wezen and Adhara form a prominent pair beneath the dog star, and these three — Sirius, Wezen and Adhara — can help guide you to Messier 93. What’s maybe even more key, however, is to remember the imaginary line formed by Orion’s belt, which you can connect to Sirius, and continue extending it.

Rather than curve that imaginary line towards Wezen, Adhara and the other naked-eye stars in that vicinity, allow that bright pair to push your Orion’s belt-to-Sirius line slightly away from it, towards instead the naked-eye stars ξ Puppis and the slightly brighter ρ Puppis a little farther along.

Because if you can train your binoculars or telescope on ξ Puppis, just a smidge over a degree north of that naked-eye star you’ll find the last open cluster ever discovered by Messier himself: Messier 93!

Described lackadaisically by Messier as a:

Cluster of small stars, without nebulosity, between the Greater Dog and the prow of the ship,

upon its discovery in 1781, it was just two years later that Caroline Herschel began her own catalogue with this very object — becoming the first woman to use her own telescope to catalogue observations — and realized what was truly going on here.

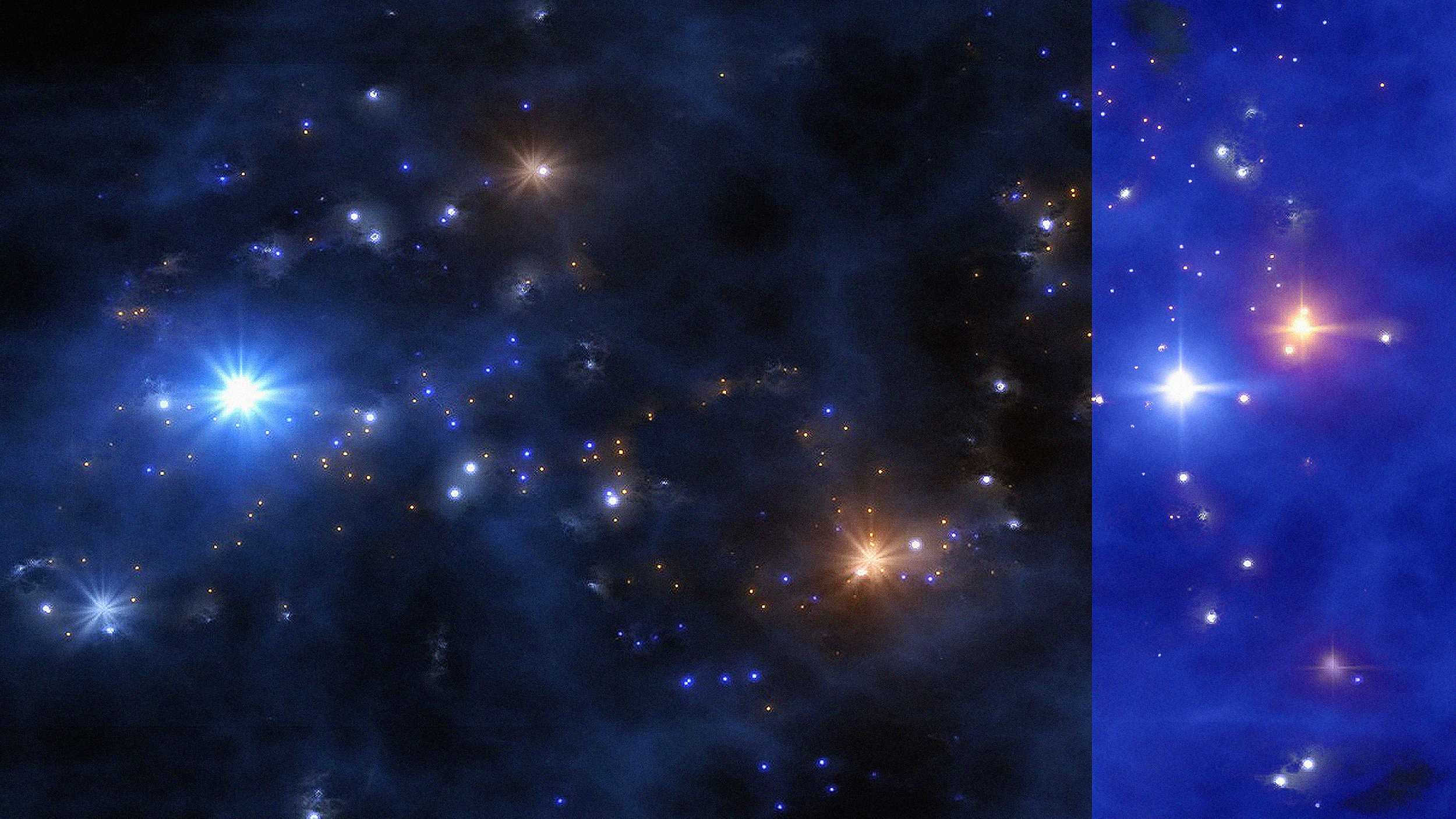

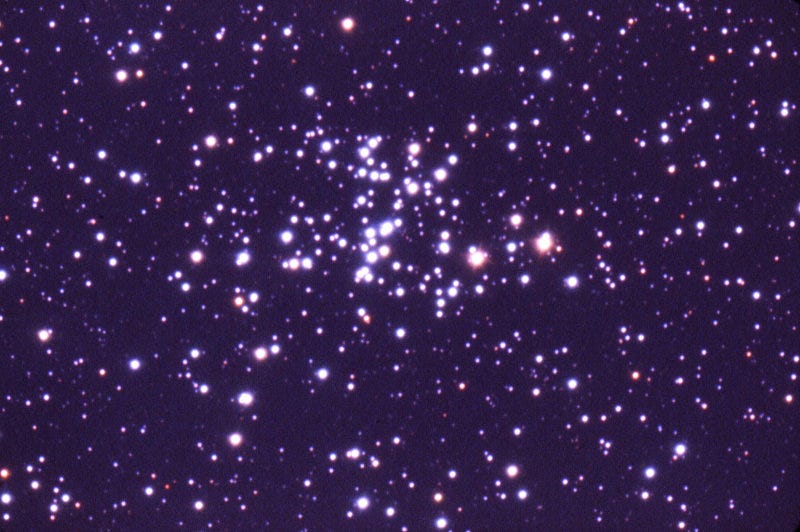

This is not a cluster of very small stars, as Messier had recorded, but of stars that are very far away, at a distance of some 3,600 light-years. Based on the colors, brightnesses and abundance of blue giants in the cluster — including a number of B-class stars — we can tell that this cluster is only about 100 million years old, or just 2% the age of the Solar System.

But the next stars to die in this cluster won’t be the blue giants, they’ll be the red giants which have already run out of hydrogen fuel in their core. A number of such stars can be found with just a cursory glance at this cluster, but are really highlighted in an infrared view, such as the one provided by the Two-micron All-Sky Survey, below. (The two brightest ones really stand out!)

At a more refined level, there are at least 80 identified stars present in this cluster, which spans maybe 20 to 25 light-years in diameter, with it very likely that there are many hundreds present inside. As is often the case, it quickly becomes very difficult to tell which of the faintest stars are members of the cluster itself, and which are background stars of the galactic plane.

This is a problem for the vast majority of open clusters, and for almost all the open clusters in Messier’s catalogue. The vast majority of star formation in our galaxy takes place along the spiral arms, which means that virtually all open star clusters — or places where star formation recently took place — will not only be found in the galactic plane, but at a particular distance based on their location relative to the galactic center and their age.

And Messier 93 is no exception!

Even though it’s never been viewed with the Hubble Space Telescope, it’s really remarkable what amazing astrophotos can be taken from the ground by a dedicated amateur these days. Take a look at the core region as imaged by Jim Misti with a 32″ (0.8 m) telescope!

How many faint stars are in there, lost against the glare of the brightest stars of the cluster? Hundreds? Maybe even thousands? Remember that Sun-like stars are a thousand times dimmer than the brightest ones in this photo, and that the Sun is intrinsically brighter than 95 percent of stars! Ponder that, along with what else lies inside of this star cluster, as we bring today’s Messier Monday to a close.

Including today, we’ve looked at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back again next week, for a new deep-sky treat from the night sky, and an all-new Messier Monday!