Messier Monday: The Black Eye Galaxy, M64

A uniquely-darkened spiral galaxy is one of the most unusual sights in the night sky. But what gives it its one-of-a-kind appearance?

“Some day I hope to meet you. When that happens you’ll need a new nose, a lot of beefsteak for black eyes, and perhaps a supporter below!” –Harry Truman, to a music critic who panned his daughter’s singing

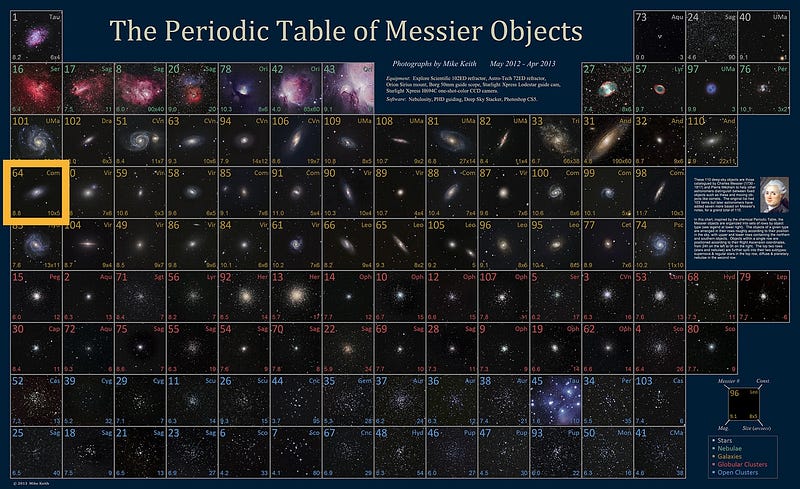

It’s time for one of my favorite Messier objects tonight, visible in the early part of the night. There are 110 deep-sky objects in the Messier catalogue, and in many ways, the most spectacular are the galaxies located far beyond our own Milky Way. There are a whopping 40 galaxies represented in the Messier Catalogue, more than any other class of object.

The combination of the Moon not rising until much later in the evening along with the end of February heralding the rising of a number of galactic targets in the northeast makes this an ideal time — if you can withstand the cold — to look for some of the most distant objects visible from Earth.

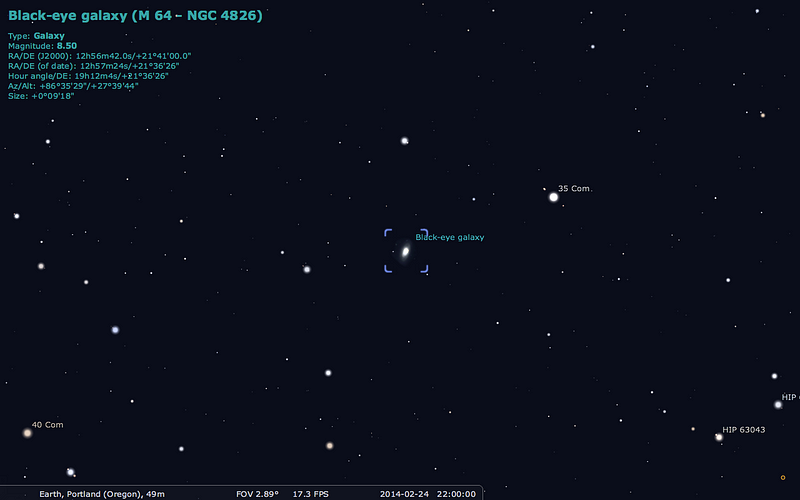

For today’s Messier Monday, let’s take a look at one of the most unique spiral galaxies not just in the Messier Catalogue, but in the entire night sky: Messier 64, the Black Eye Galaxy. Here’s how to find it.

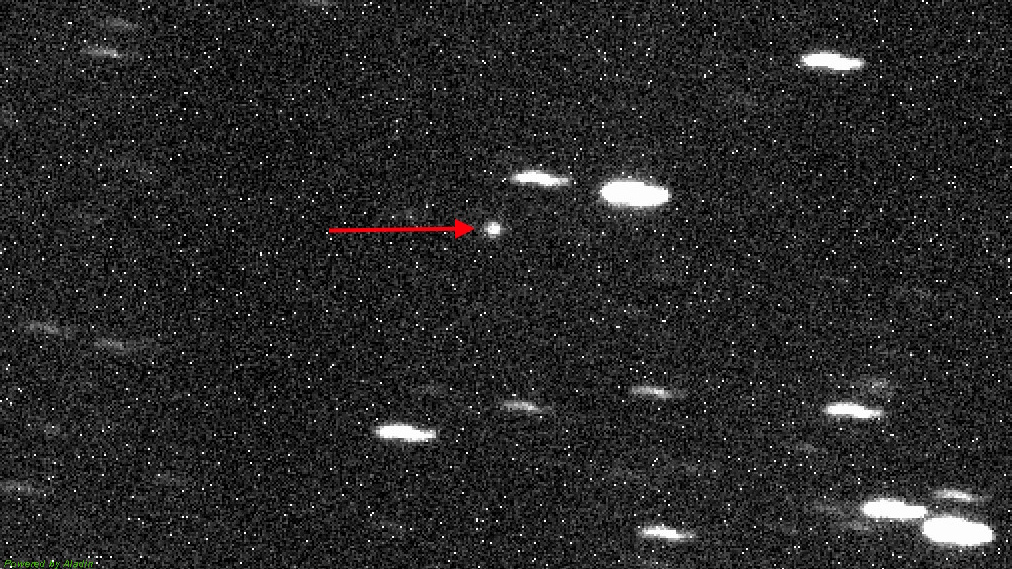

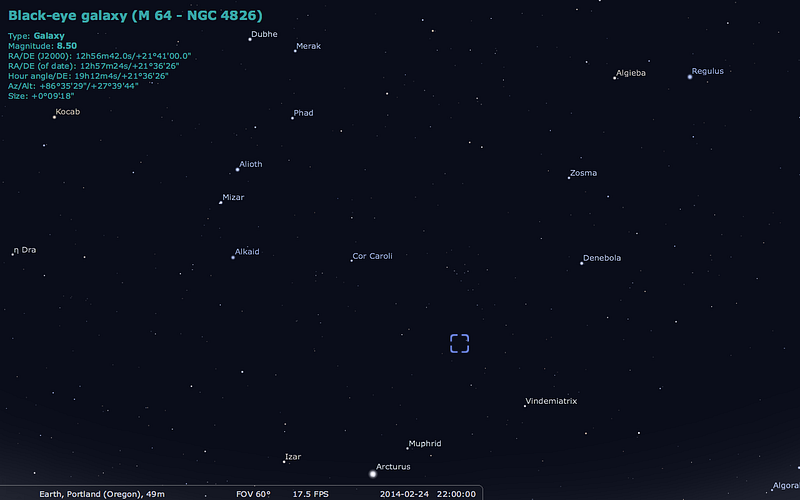

From the northern hemisphere, after sunset, look for the Big Dipper rising high in the northeast skies, with the prominent constellation Leo farther to the east. If you move perpendicularly towards Leo from the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle, you’ll come to the prominent star Cor Caroli, while if you continue the line formed from Leo’s two brightest stars — Regulus and Denebola — you’ll arrive at Vindemiatrix.

It’s these two stars — Cor Caroli and Vindemiatrix — that will help you locate Messier 64. Draw an imaginary line between them, and start at Vindemiatrix, backtracking towards Cor Caroli.

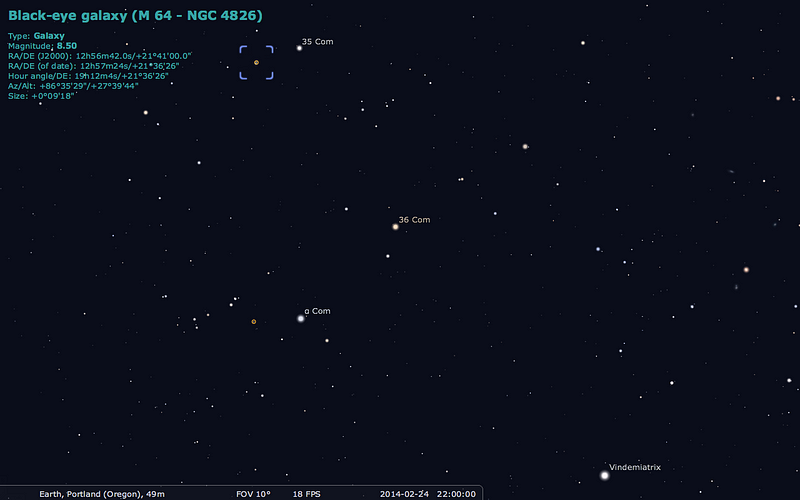

There are two naked-eye stars that roughly head towards Cor Caroli: Diadem (also known as α Comae Berenices) and the slightly fainter (and slightly more in line) 36 Comae Berenices. If you continue to follow the line from Vindemiatrix to 36 Comae Berenices and beyond, you’ll arrive at the yellow giant 35 Comae Berenices, and that’s your guide to Messier 64, which lies less than a degree away.

Although it was independently discovered by Messier, he was actually the third to find it, as reported by seds.org, where they say:

M64 was discovered by Edward Pigott on March 23, 1779, just 12 days before Johann Elert Bode found it independently on April 4, 1779. Roughly a year later, Charles Messier independently rediscovered it on March 1, 1780 and cataloged it as M64. However, Pigott’s discovery got published only when read before the Royal Society in London on January 11, 1781, while Bode’s was published during 1779 and Messier’s in late summer, 1780. Pigott’s discovery was more or less ignored and recovered only by Bryn Jones in April 2002!

But this is certainly a wonderful target for anyone with a telescope, regardless of its power.

Even small telescopes can capture the bright central nucleus, the fading surface luminance as you move off to the edges, and the unique feature of this galaxy: its darkened appearance on one side only.

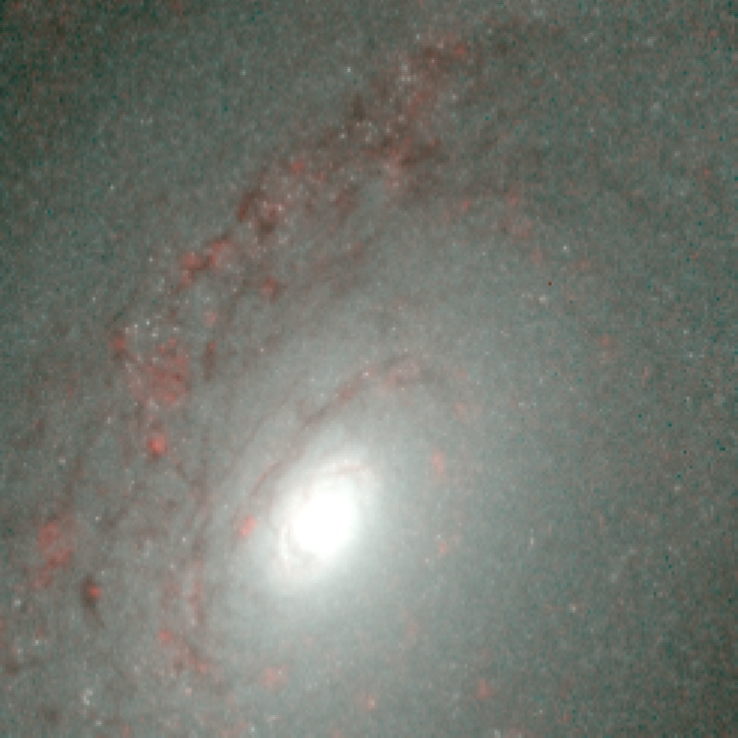

But through a more powerful telescope, we can really get a handle on what’s at play here.

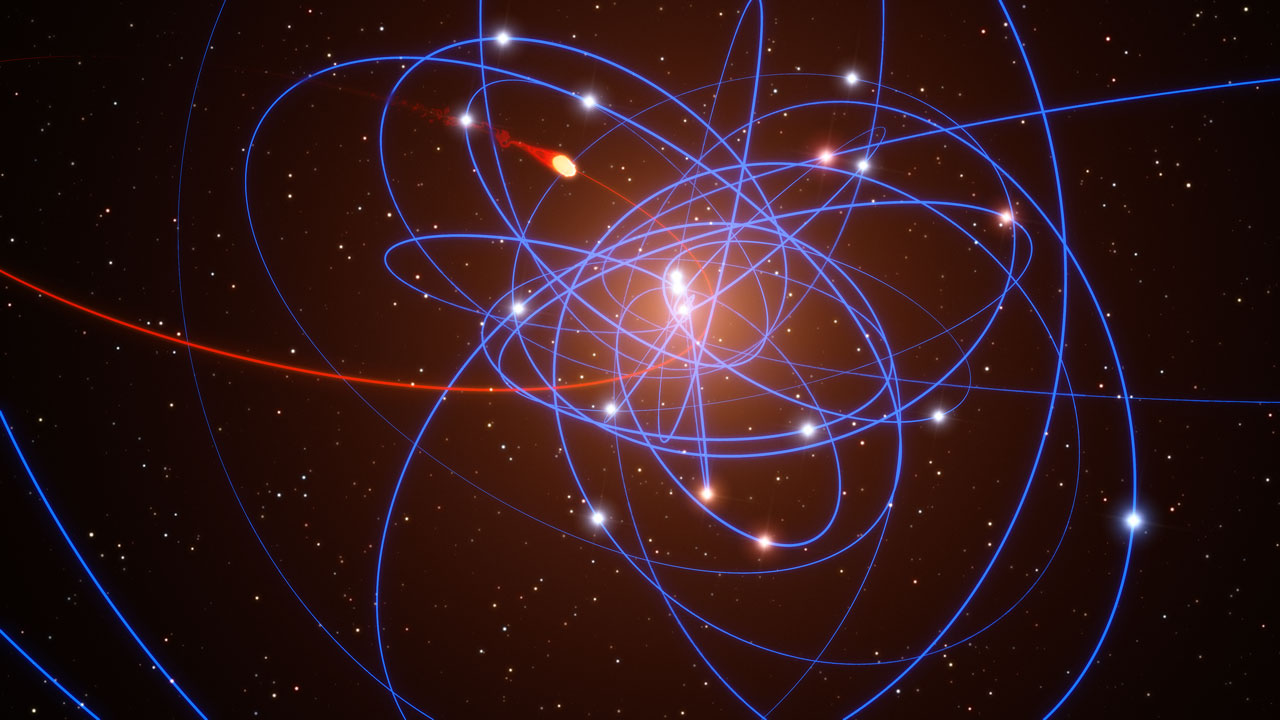

The bright central nucleus appears to spiral outwards in a large number of arms in the inner portion, yet there appear to only be one very large, sweeping one that encircles the galaxy over and over on the outer parts. The “black eye” appearance — also called the evil eye or the sleeping beauty by some — is due to a prominent partial dust lane, likely evidence of a recent merger.

This is also a highly unusual galaxy for a number of other reasons: despite being so bright, its distance is poorly measured (estimated at 24 million light years), as there are no known cepheids inside, highly unusual for a galaxy this close. Despite the recent merger evidence, there hasn’t been a single supernovae observed in it, ever.

As you can see from long-exposure images like Andrea Tamanti’s, above, the outer arms extend for a very large distance, about 65,000 light-years in diameter at a distance of 24 million light-years, whereas the inner dust lane extends for only about a quarter of that.

And — despite recent Hubble observations — there’s still an intense debate as to just what’s causing this unique dust feature.

As revealed in the infrared (above), there is an intense, bright population of new stars, and the dust in the very inner region rotates in the same direction. However, in the outer dusty region (out of frame of this image), the interstellar dust rotates in the opposite direction from all the stars. Yet it’s the co-rotating inner region where a population of new, young stars have recently formed.

So that’s a clue, and it provides us with two reasonable possibilities for this galaxy’s appearance:

- A satellite galaxy collided with M64 maybe a billion years ago, and the dust from that is responsible for what we’re seeing.

- The dust feature is due to infalling matter in the galaxy’s halo, accruing asymmetrically onto the galaxy’s core.

The best view — and the most suggestive answer between these possibilities — comes from Hubble’s WFPC2 in the visible, shown below.

Although, to be frank, we could really use a quality N-body simulation to learn more, what does the image above show you about the position of the dust lanes? Does it appear to you — like it does to me — that on the right side of the image, there’s a tremendous amount of foreground dust between the plane of the galaxy and our eyes? Whereas on the left, it looks like there are more stars between the dust lanes and our eyes, yet it still appears to be there?

Based on this, I would assume that there was a satellite that merged with M64, and that it did so not only with its rotation in the opposite direction, but that it merged asymetrically. I’d be willing to bet that if we could view this galaxy from the opposite side, we’d find a matching prominent dusty feature where the plane of our galaxy obscures our view today. And I’d be willing to admit the possibility that the central, “black eye” region and the dusty outer arms have different origins from one another. Whatever the case, this galactic wonder will surely keep us busy for years to come as we try and uncover the root of its mysterious appearance! I’ll leave you with one final true color image…

…as we wrap up today’s Messier Monday! Including today’s object, we’ve profiled the following deep-sky wonders:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back next week for another deep-sky wonder and another fantastic story that the Universe tells us about itself, only here on Messier Monday!

Have something to say? Head on over to the Starts With A Bang forum at Scienceblogs and join the discussion!