Messier Monday: The Sunflower Galaxy, M63

A beautiful spiral just outside the Big Dipper holds many secrets that can teach us about our own Milky Way!

“If I were a flower.. I would be a sunflower.

To always follow the sun, Turn my back to darkness,

Stand proud, tall and straight even with my head full of seeds.” -Pam Stewart

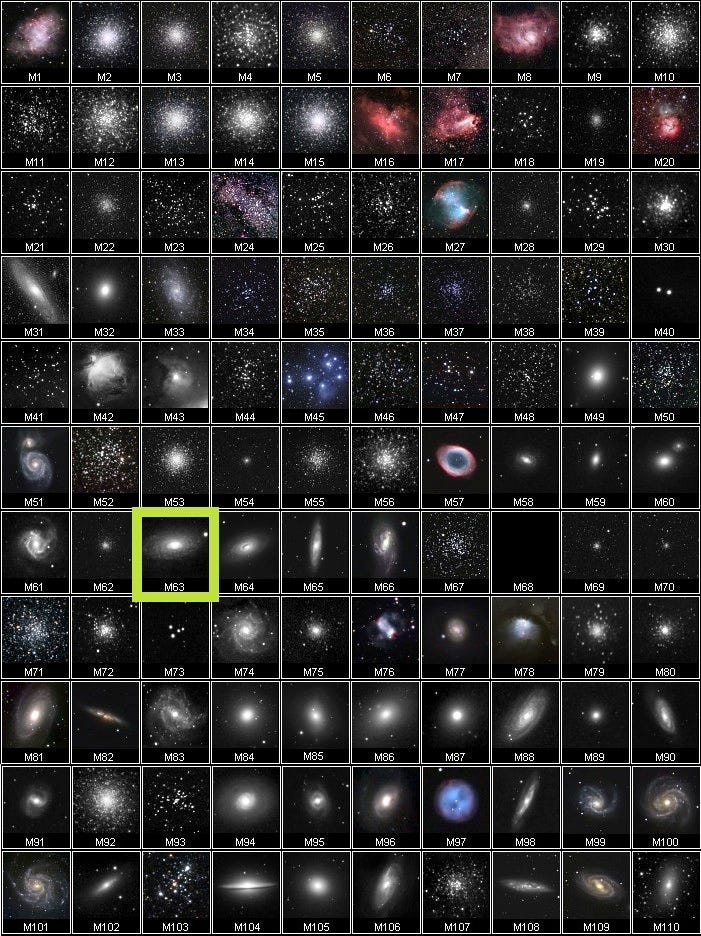

Welcome to the first Messier Monday at our new home here on Medium! There are a total of 110 deep-sky objects that make up the Messier catalogue, the first large, accurate catalogue of nebulae, star clusters and galaxies in the night sky. All of the Messier objects can be seen with simple astronomical equipment — either binoculars or a small telescope — and we went through 63 of them on our old site.

Well, to kick off the rest of them, let’s take a look at the 63rd object itself!

Discovered by Messier’s assistant, Pierre Méchain in 1779, this lonely little spiral has a tremendous story to tell us, if only we listen to it. Find it just as the Moon begins to go down tonight from north enough latitudes (assuming you’re not freezing out there), or at any point as the year goes on, assuming the Big Dipper is high enough in the sky! Here’s how.

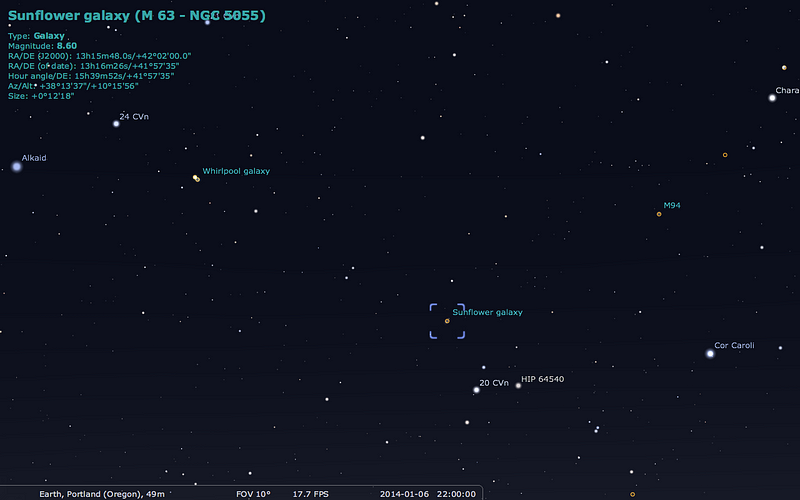

The entire sky always appears to rotate about the north (or south, depending on your hemisphere) pole, due to the Earth’s rotation about its axis. By about 10 PM, the Big Dipper will be clearly visible in the northeast portion of the sky. The tip of the handle is represented by the bright blue star Alkaid, and a few degrees “below” it is the prominent Cor Caroli, only slightly dimmer.

To find Messier 63, draw an imaginary line connecting those two.

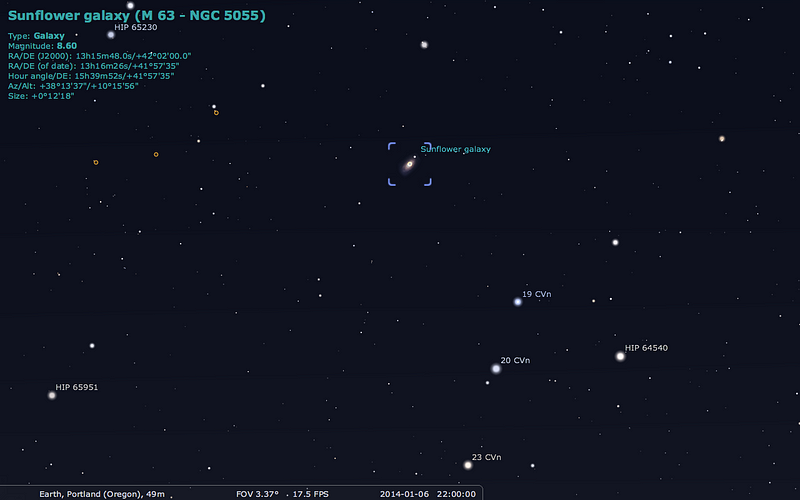

If you look slightly closer to Cor Caroli and a little farther away from the “cup” of the dipper, you’ll easily see the two naked-eye stars labeled above: 20 Canum Venaticorum and HIP 64540. If you look a little deeper, you’ll see two more stars in that same vicinity that may or may not be visible to the naked eye (dependent on light pollution), and through binoculars or a telescope on low-magnification, they’ll be your guides to Messier 63.

Three of these stars make a line: 23, 20 and 19 Canum Venaticorum, while HIP 64540 lies off to one side. These four stars make a rough “arrowhead” shape that points in the direction of Messier 63: the Sunflower Galaxy! (Slightly more towards the “three star” rather than the “two star” side.)

Through a low-power telescope, here’s what you’re likely to see, something very similar to what Messier and Méchain might’ve seen more than 200 years ago.

A “smudge” on the sky, with a bright, asymmetric center that dims as you move out towards the edges, this is what most galaxies look like through smaller telescopes. This was the first original discovery of Méchain, and Messier recorded it as follows:

Nebula discovered by M. Méchain in Canes Venatici. M. Messier searched for it; it is faint… it contains no star, & the slightest illumination of the micrometer wires makes it disappear.

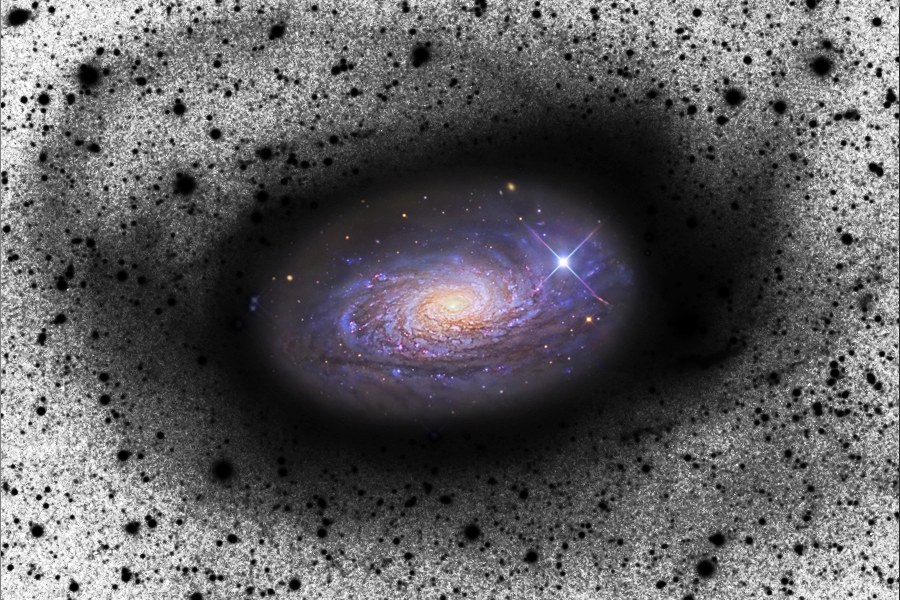

Its spiral structure wasn’t discovered until the advent of a 72″ (1.8 meter) telescope in 1850, but modern astrophotography techniques can bring that out with much smaller telescopes!

Although technically classified as part of a group, the Sunflower Galaxy is very much alone in its neck of the woods, with no other discernible galaxies in its vicinity for many millions of light-years. This, however, is a very recent development, as it cannot hide the clues of its history!

First off, you’ll notice how incredibly extended this galaxy is, and how those outer arms extend far beyond the bright extent of the galaxy’s normal arms! The next thing you might notice are the bright pink regions that line large sections of the main galactic structure. And finally, you might notice that this galaxy is quite asymmetrical, and even slightly warped.

These three observations are strong evidence that, in the recent past, the Sunflower Galaxy devoured a smaller neighboring satellite. The warping is typical when you get a gravitational perturbation messing up the “perfect” disk-like structure, the pink regions are evidence of new star formation, triggered by mergers and galactic cannibalism, and the extended structure — showcased fabulously in the “negative” image below — is the result of tidal disruption (or in this case, destruction) of the recently devoured neighbor!

While most spiral galaxies typically have just a couple of spiral arms, winding around the galaxy a large number of times, it’s pretty apparent that Messier 63 is much more complex than that. First off, you can clearly see many different dust lanes branching off from the arms as they go around, and this teaches us something important about the galaxy: it’s been quite for a very long time!

As galaxies age, their spiral arms tend to wind up, as the inner portions make more revolutions over millions of years than the outer portions. As the arms continue to twist progressively more and more over time, the arms become more difficult to distinguish. Eventually, it produces a structure like you see above, where the spiral arms are described as flocculent, with patchy, discontinuous and a large number of arms. And this is highlighted by the dark, dusty lanes.

Dust particles are the ones that block light, and they’re typically just a few microns in size. Even though they’re only about 1% of the interstellar matter — with the rest in the form of gas — they’re the ones that do the vast majority of the light-blocking.

But we can see through those dust lanes if we look with a different wavelength of light: the infrared!

As seen via the Spitzer Space Telescope, the infrared traces out the gas that will form the next generation of stars: right along the spiral arms!

In contrast with this, we can see where the current generation of bright young stars are by looking in the Ultraviolet.

The ultraviolet traces out the hottest, bluest stars, which show us where the most recent locations of star formation have been.

This beautiful spiral galaxy is located some 37 million light-years away, had a supernova go off in it back in 1971, and is estimated to have a supermassive black hole at its center that’s up to 30 million Suns in mass! Some argue that this cosmic sunflower may actually be significantly closer, but at a distance of 37 million light-years that would mean this galaxy was about 136,000 light-years across, or more than a third again as large as our galaxy!

And that doesn’t even include the (temporary) extended structure, which more than doubles this galaxy’s true extent! And with that, we’ll wrap up the very first Messier Monday of the new year, and of the new blog! Including today, we’ve looked at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back again next week, for a new deep-sky treat from the night sky, and an all-new Messier Monday!