How a nearby supernova could reveal dark matter

- On average, modern spiral galaxies like our Milky Way experience somewhere around one supernova per century, but we haven’t seen one directly since 1604.

- The next time one goes off, however, we’ll have something working for us that we haven’t had in all the supernovae to come before: an array of powerful, sensitive neutrino detectors.

- Neutrinos are supposed to carry away some ~99% of a supernova’s energy, but if there’s an unexpected deficit, dark matter’s presence and interplay will be to blame.

In this Universe, few mysteries loom as large as the puzzle posed by dark matter. We know, from the gravitational effects we observe — at all times, on scales of an individual galaxy and upward, and everywhere we look — that the normal matter in our Universe, along with the laws of gravity that we know, can’t fully account for what we see. And yet, all of the evidence from dark matter comes indirectly: from astrophysical measurements that don’t add up without that one key missing ingredient. Although that one addition of dark matter solves a wide variety of problems and puzzles, all of our direct detection efforts have come up empty, yielding only null results.

There’s a reason for that: all of the direct detection methods we’ve tried rely on the specific assumption that dark matter particles couple to and interact with some type of normal matter in some way. This isn’t a bad assumption; it’s the type of interaction we can constrain and test at this moment in time. Still, there are plenty of physical circumstances that occur out there in the Universe that we simply can’t recreate in the lab just yet. If dark matter interacts with normal matter under those extreme conditions that we cannot reproduce here, then it will be the laboratory of the Universe — not an experiment on Earth — that reveals dark matter’s particle nature to us.

Here’s how the Milky Way’s next supernova might just be the perfect candidate for showing us that dark matter doesn’t just exist, but that it interacts with normal matter in some non-trivial way.

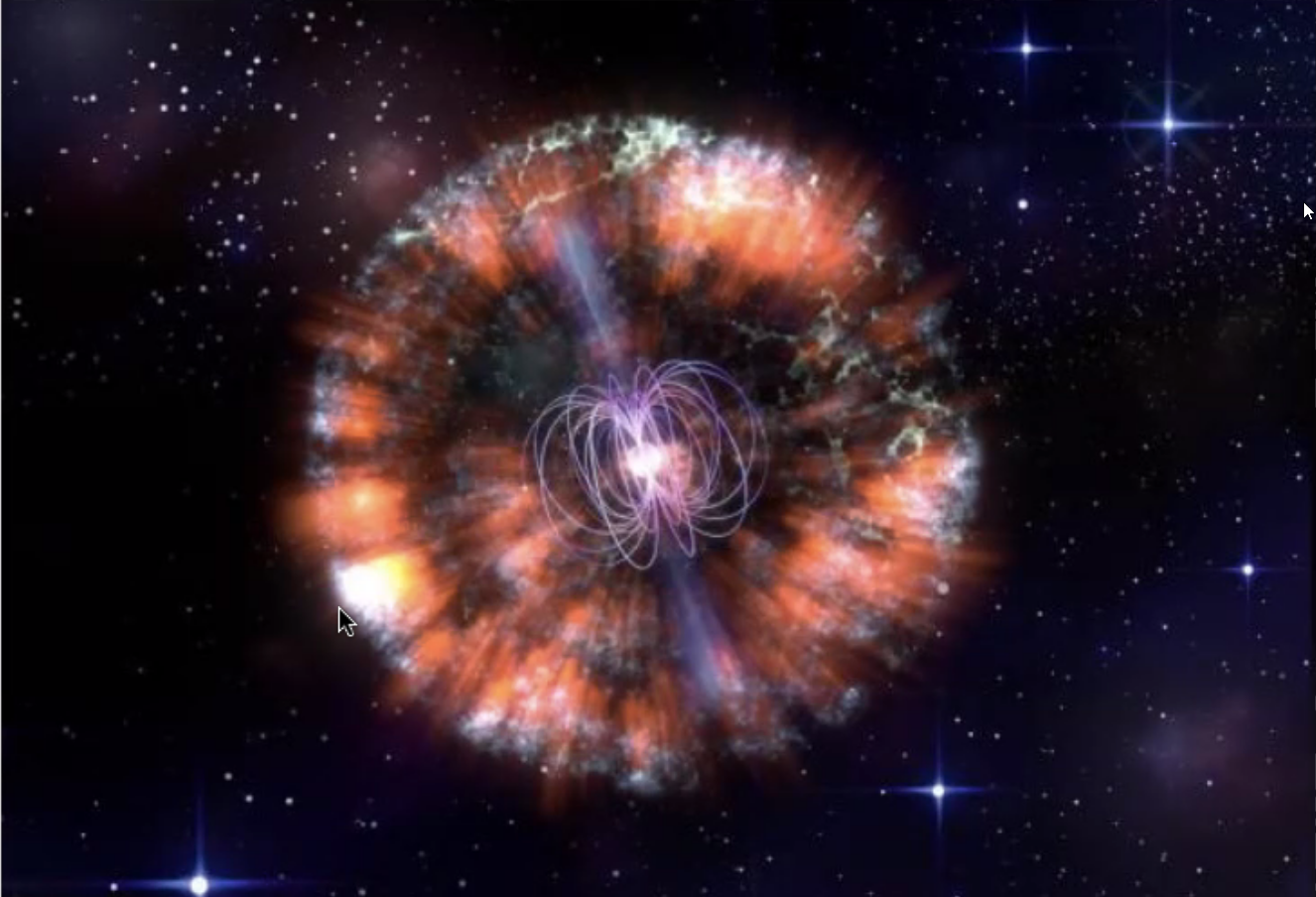

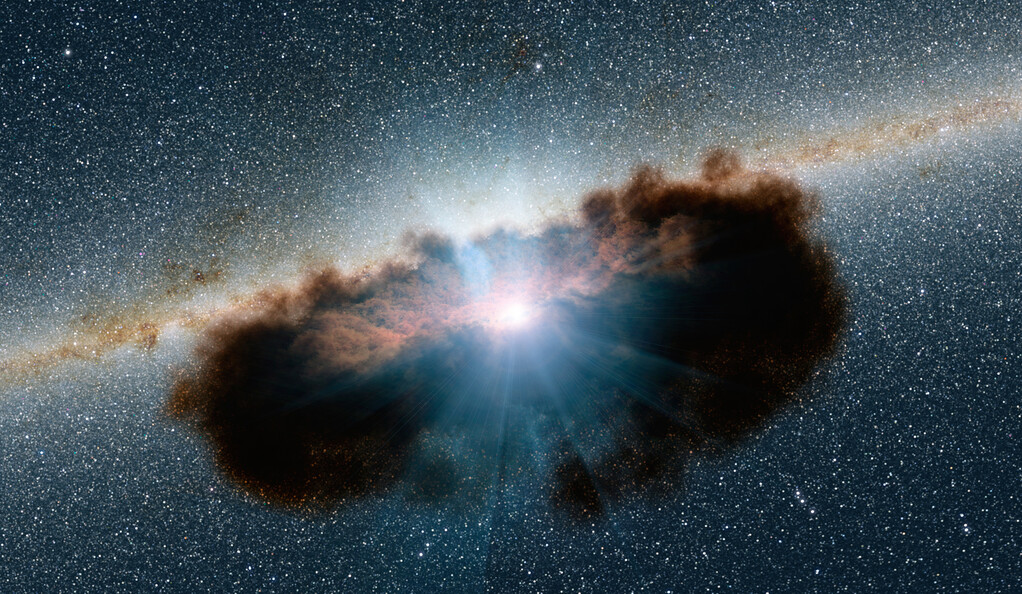

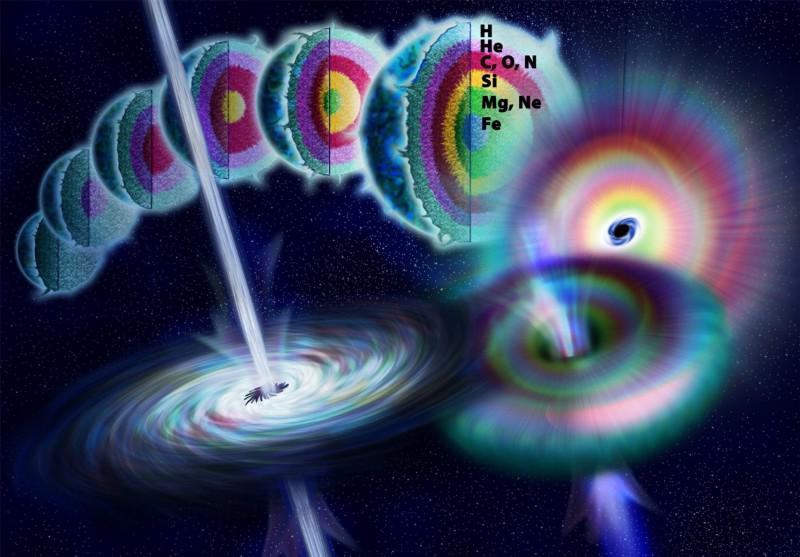

Although there are numerous types of supernovae that can occur within the Universe, the overwhelming majority that we see are of one particular variety: a core-collapse (or type II) supernova. Whenever stars are born in large numbers, they follow a specific mass distribution, where less massive stars are formed in great numbers but more massive stars, although far fewer in number, represent a significant portion of the total mass of the newly formed stars. The most massive among the new stars that form in a star-formation episode, the ones that are born with more than about 8-10 times the mass of the Sun, will be destined to die in a core-collapse supernova after only a few million years have elapsed.

Over the history of astronomy, we’ve detected supernova signals across the electromagnetic spectrum — in various wavelengths of light — for every supernova that we’ve ever measured. However, the overwhelming majority of a core-collapse supernova’s energy doesn’t get carried away in the form of light at all, but rather in the form of neutrinos: a class of particles that only interacts very weakly with all other forms of matter, but which plays an immense role in nuclear processes. In a core-collapse supernova, some ~99% of all the energy released is released in the form of neutrinos, where they easily escape the star’s interior and carry energy away very efficiently. It’s this process that typically leads to the core’s implosion and the formation of either a neutron star or a black hole as a result of a core-collapse supernova.

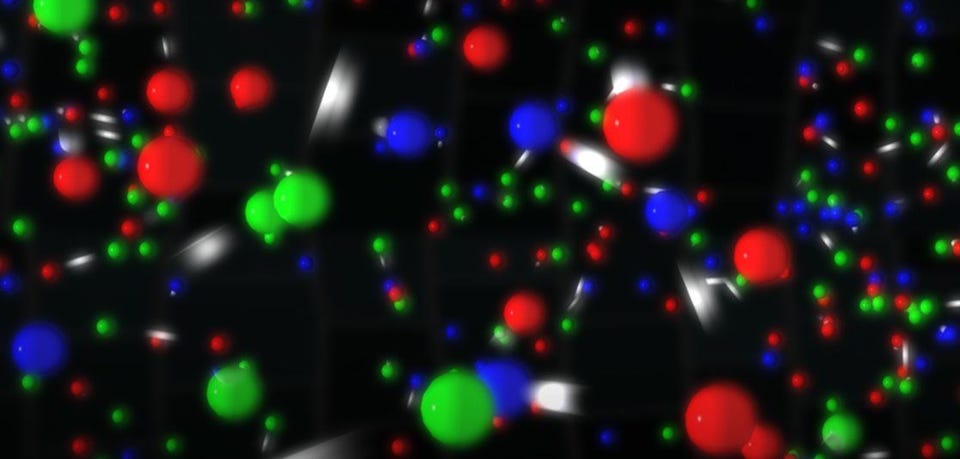

In particle physics experiments that we perform in the lab, neutrinos are only very, very rarely detected. Neutrinos have three properties that account for why this is the case.

- Neutrinos only interact through the weak nuclear force, which is a highly suppressed interaction under normal conditions relative to either the forces that hold atomic nuclei together (the strong nuclear force) or the forces that govern charged particles, electric currents, and light (the electromagnetic force).

- Neutrinos have a very small cross-section with normal matter: things like atoms, protons, etc. For a typical neutrino produced in a Sun-like star, for example, it would take about a light-year’s worth of lead as a detector to have about a 50/50 shot of having your neutrino interact with them.

- And the neutrino cross-section scales with neutrino energy; the more energetic your neutrino is, the more likely it is to interact with matter. Neutrinos made from ultra-high-energy cosmic rays are far more likely to interact with matter than a supernova-created neutrino, a solar neutrino, or (most difficult of all) a neutrino left over from the Big Bang.

If something only produces a small number of neutrinos, you have to be both very nearby and must wait a long time (or, alternatively, build an enormous-and-pristine neutrino detector) before you can be confident you’ve robustly detected the neutrino signal you’re searching for.

However, if an event produces an enormous number of high-energy neutrinos, and produces them either all at once or over an extremely short period of time, the detectors that are operating all across the globe will have no way of avoiding this sudden neutrino signature that permeates the entire planet. We know that galaxies like the Milky Way produce supernovae roughly once per century, with some actively star-forming galaxies producing more than one per decade while other, less active galaxies produce them only a few times per millennium. As a large but quiet galaxy, we’re on the slower side of supernova producers, but we’re also far from the slowest known example.

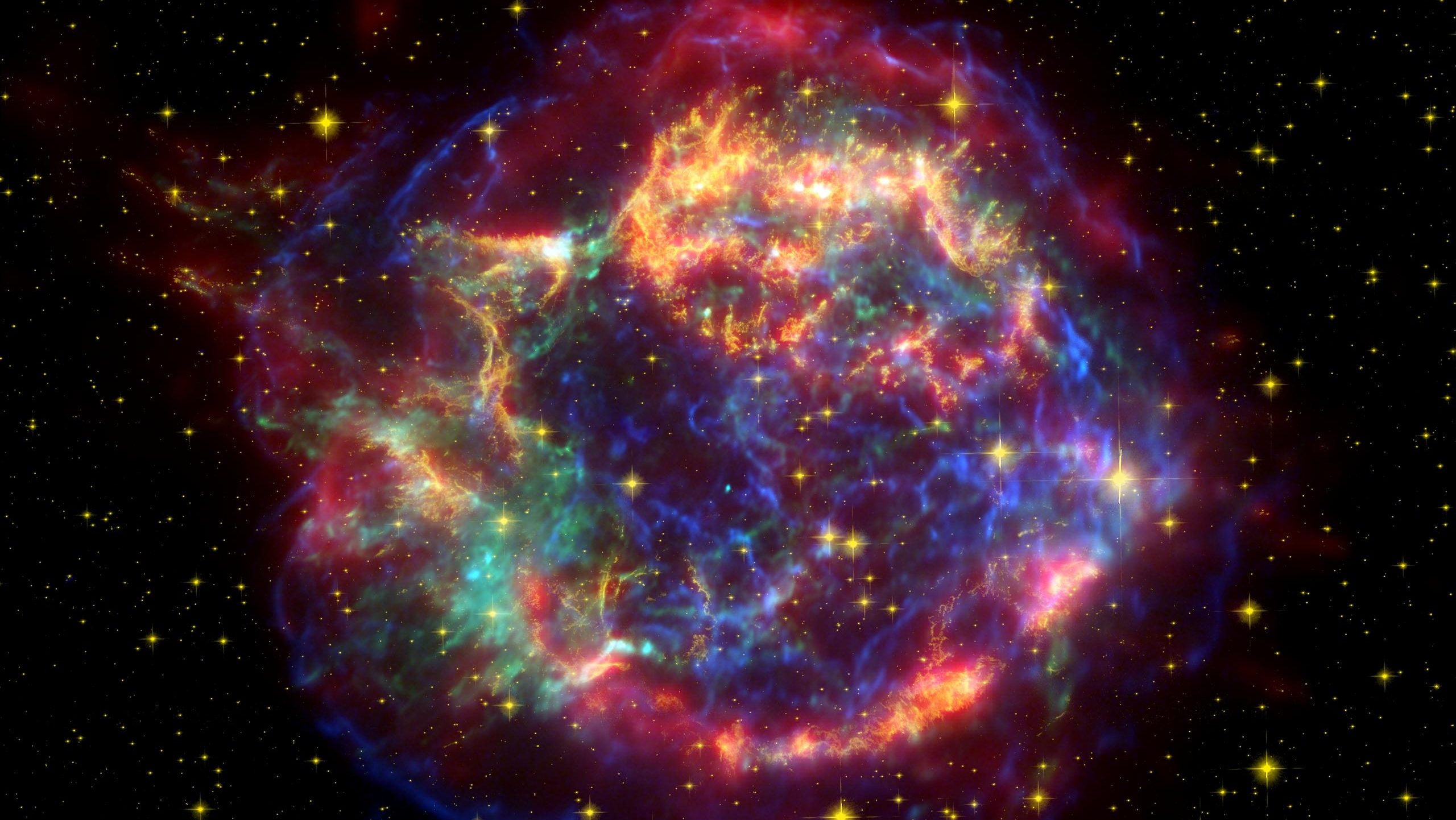

Although the last naked eye supernovae within the Milky Way occurred in 1604 and 1572, there have been two others that have occurred in our own galaxy since that time:

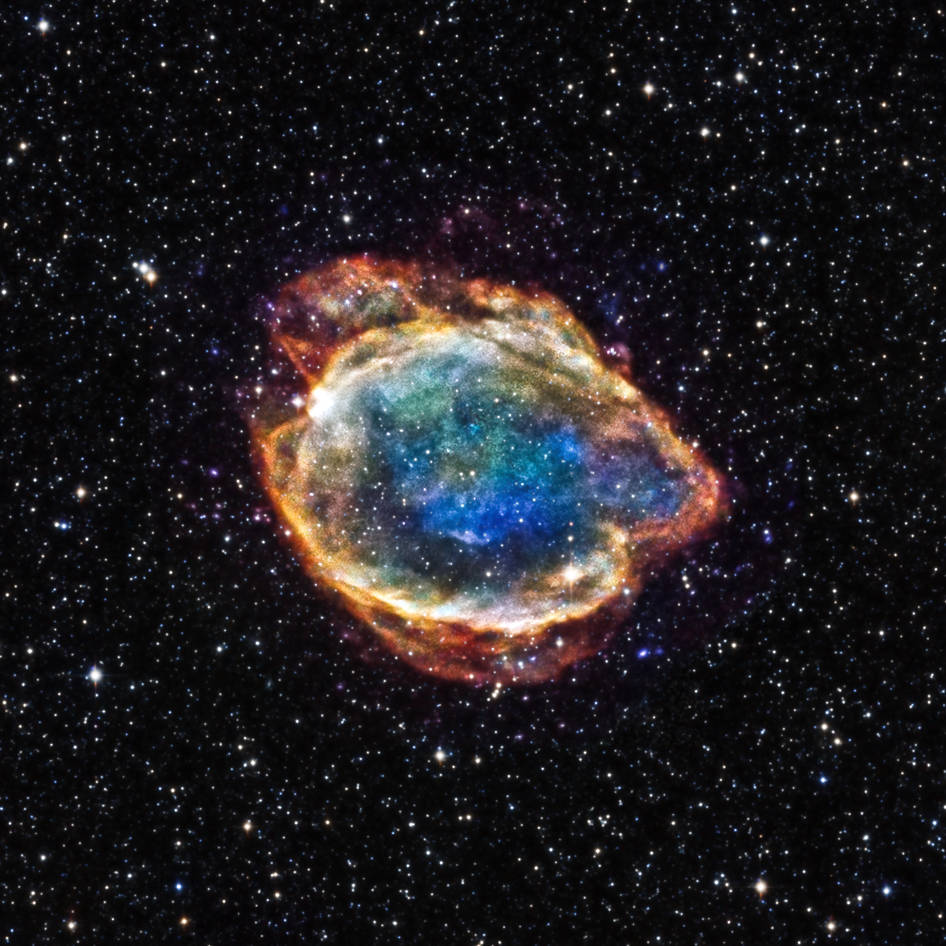

- Cassiopeia A, which occurred in 1667 but was obscured by light-blocking galactic dust in that direction,

- and G1.9+0.3, which occurred in 1898 but was near the galactic center, and thus was not visible within the plane of the Milky Way.

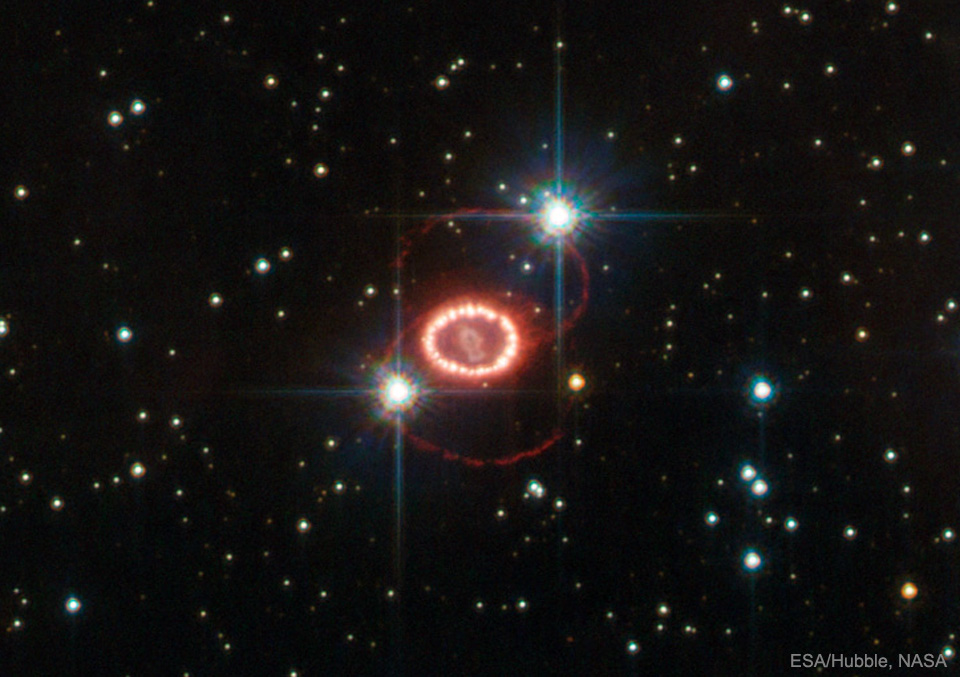

We didn’t have any neutrino detectors that were operating back in 1898 (the neutrino wasn’t theorized until 1930, and then wouldn’t be detected for the first time until the 1950s), but there were a number of apparatuses that were sensitive to neutrinos operating in 1987: when a supernova from just outside the Milky Way — in the satellite galaxy of the Large Magellanic Cloud — spontaneously detonated.

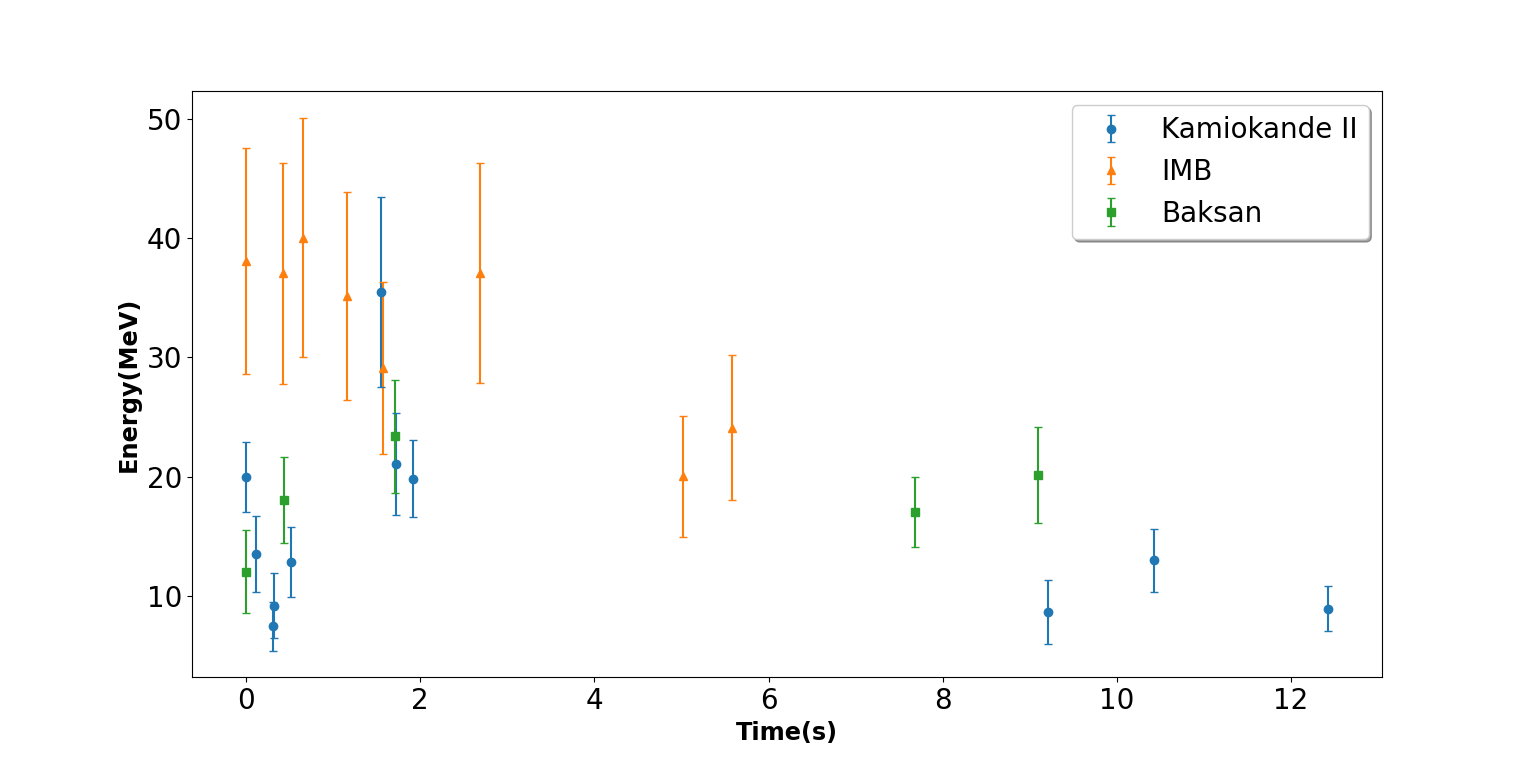

Technically, the star that underwent core collapse and became a supernova didn’t do so in 1987; it did so some ~165,000 years ago, with its light only arriving from so far away in 1987. It wasn’t the light that was the first arriving signal from this cataclysm, however; a few hours before the light signal arrived, something wonderful and unprecedented occurred: a stream of high-energy neutrinos, all localized to the Large Magellanic Cloud, struck three of our neutrino detectors here on Earth. Although only a total of just over 20 neutrinos arrived across a timespan of about 12 seconds, this event marked the birth of neutrino astronomy beyond merely the Sun, nuclear reactors, and those created by cosmic rays striking Earth’s atmosphere.

What’s vital to understand about this supernova is that:

- It detonated a whopping 165,000 light-years away, well outside our Milky Way. Because the neutrinos generated in its core spread out like a sphere, we would have detected 100 times as many neutrinos if it were only 10% as distant, or 10,000 times as many if it were just 1% as distant. The closest supernova candidate to us, Betelgeuse, is only 650 light-years away; if it were to go supernova, the neutrino flux would be 64,000 times as great compared to the neutrinos from SN 1987a.

- Back in 1987, our neutrino detectors were primitive, small, and few in number. Today, we have many thousands of times the detection sensitivities as we did a scant ~35 years ago.

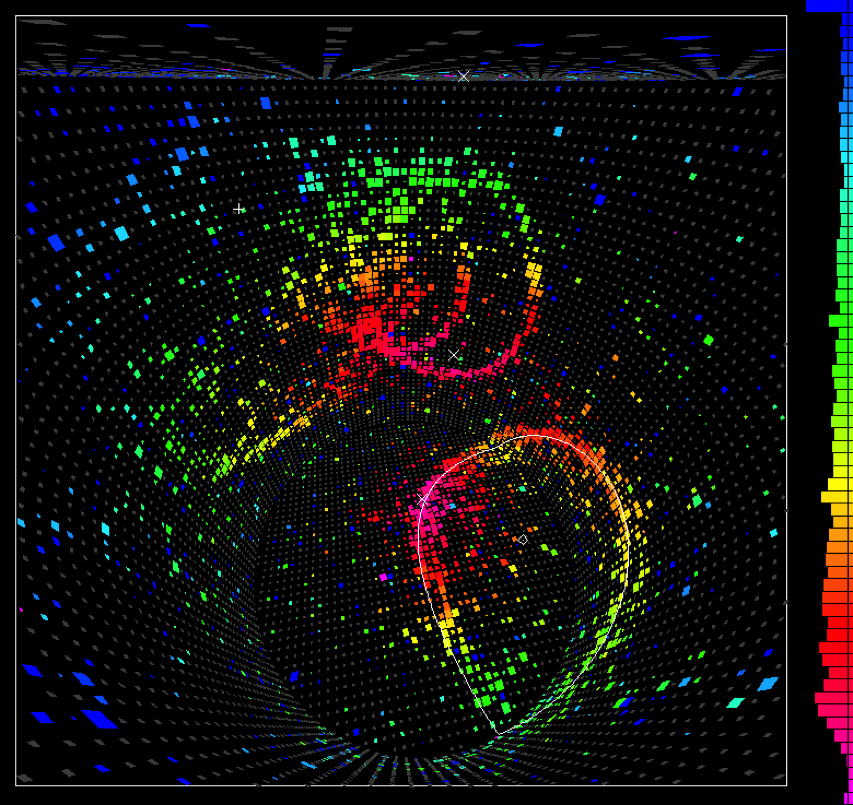

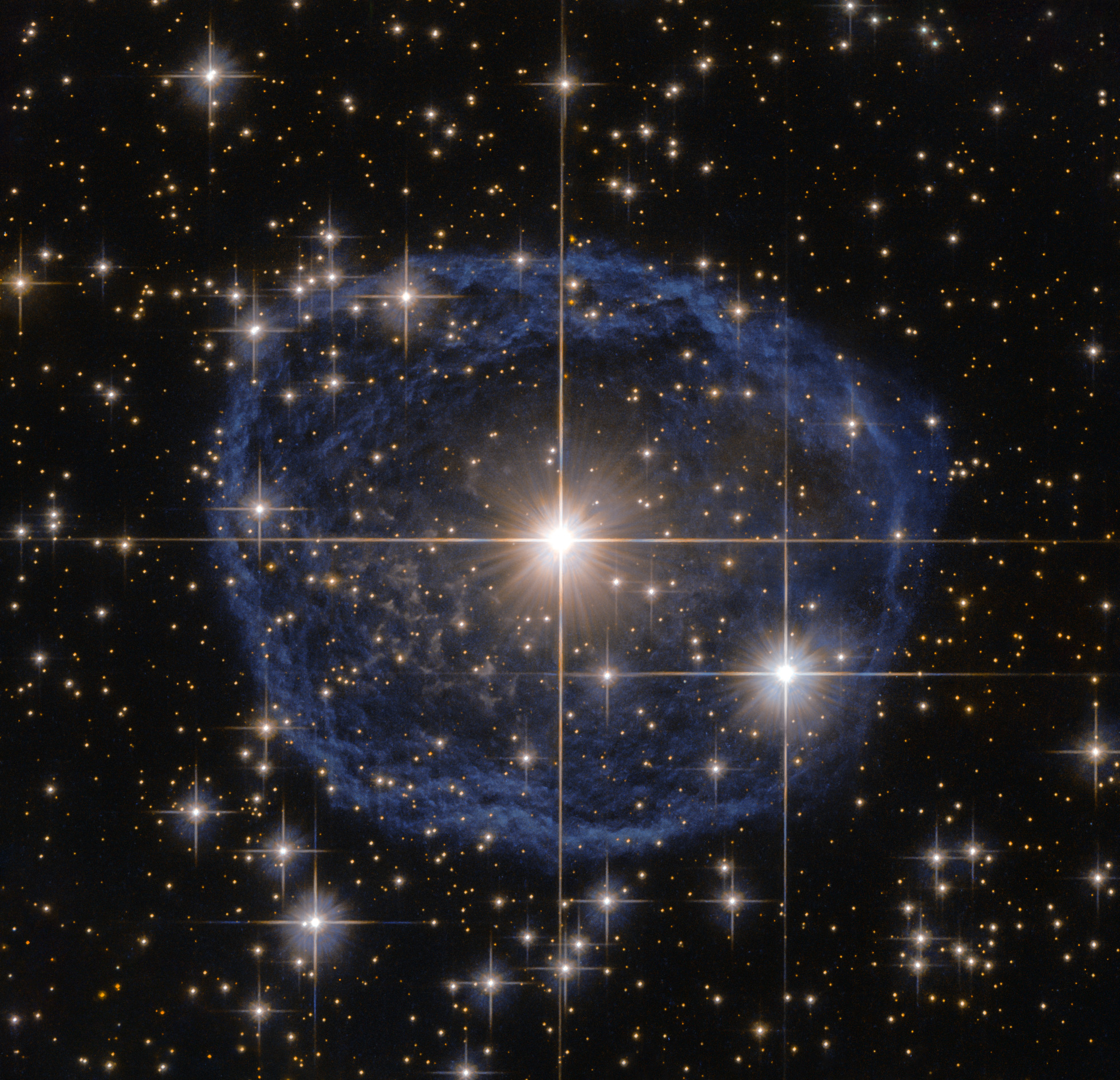

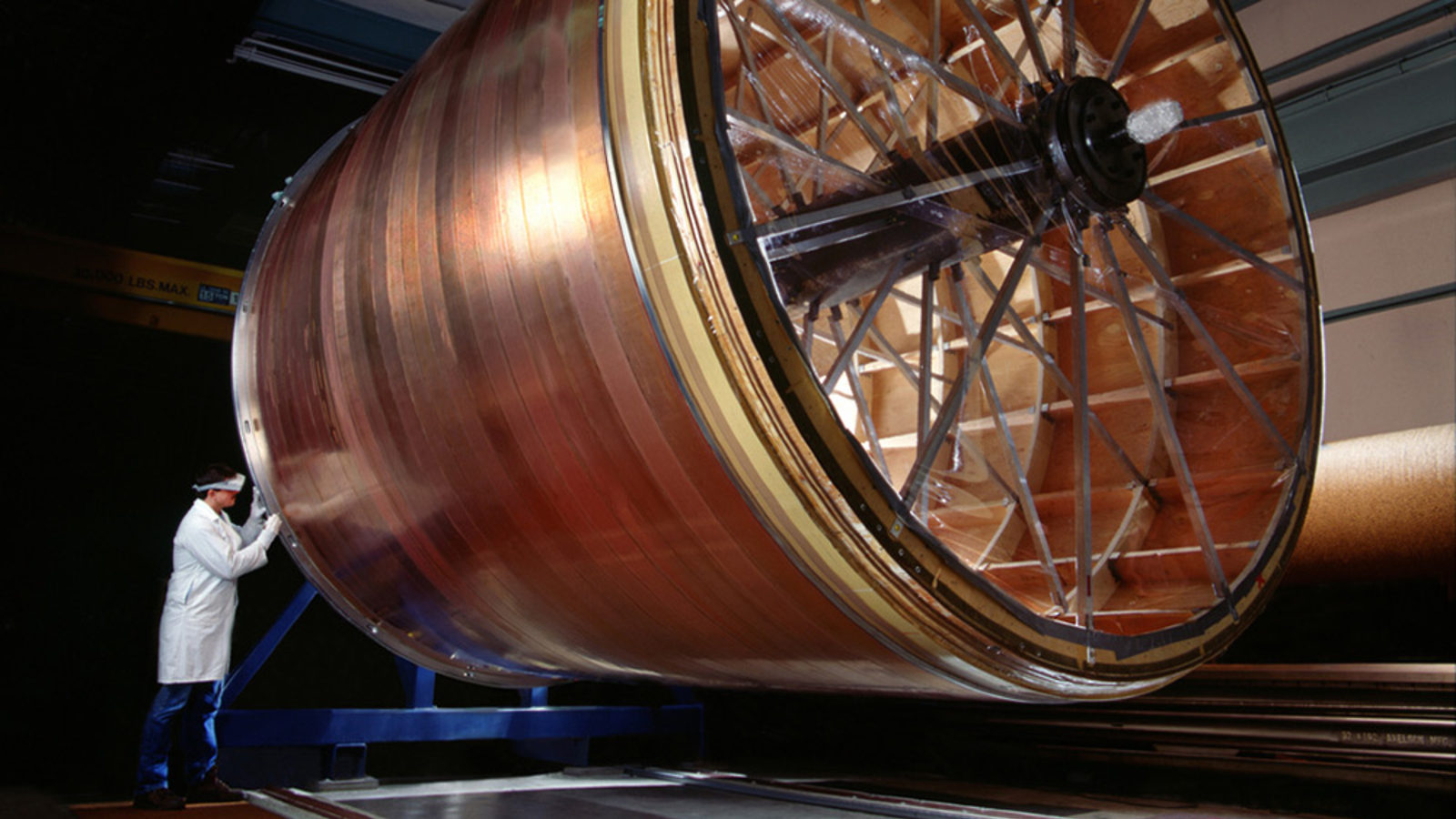

In 1987, the world’s most sensitive neutrino detector wasn’t even designed to detect neutrinos; it was designed to search for decaying protons. By building an enormous, shielded tank of water — where water is a molecule that’s rich in protons — and lining that tank with detectors that could be sensitive to even a single photon (photomultiplier tubes), any decay that resulted in a charged particle moving faster-than-light in the medium of water would be able to be successfully reconstructed.

Unfortunately for the experiment-designers, it turns out that protons don’t decay, and no such signal has ever been observed in these experiments. However, neutrinos from all sorts of cosmic sources do arrive here on Earth, where they strike the atomic nuclei in the molecules present within the tank. An energetic-enough neutrino can either:

- produce an atomic recoil,

- or can kick out a charged particle,

both of which will make a detectable signal in these experiments. Located in Kamioka, Japan, the 1987 experiment was called KamiokaNDE: the Kamioka Nucleon Decay Experiment. After that 1987 event, the experiment was swiftly renamed with the same acronym, KamiokaNDE: for the Kamioka Neutrino Detector Experiment thereafter.

Since that time, KamiokaNDE has been upgraded numerous times: to Super KamiokaNDE, Super-K, and presently, Hyper-K. Other neutrino detectors have come online, such as JUNO, IceCube, and the now-under-construction DUNE among them, the last of which ought to surpass them all in terms of sensitivity.

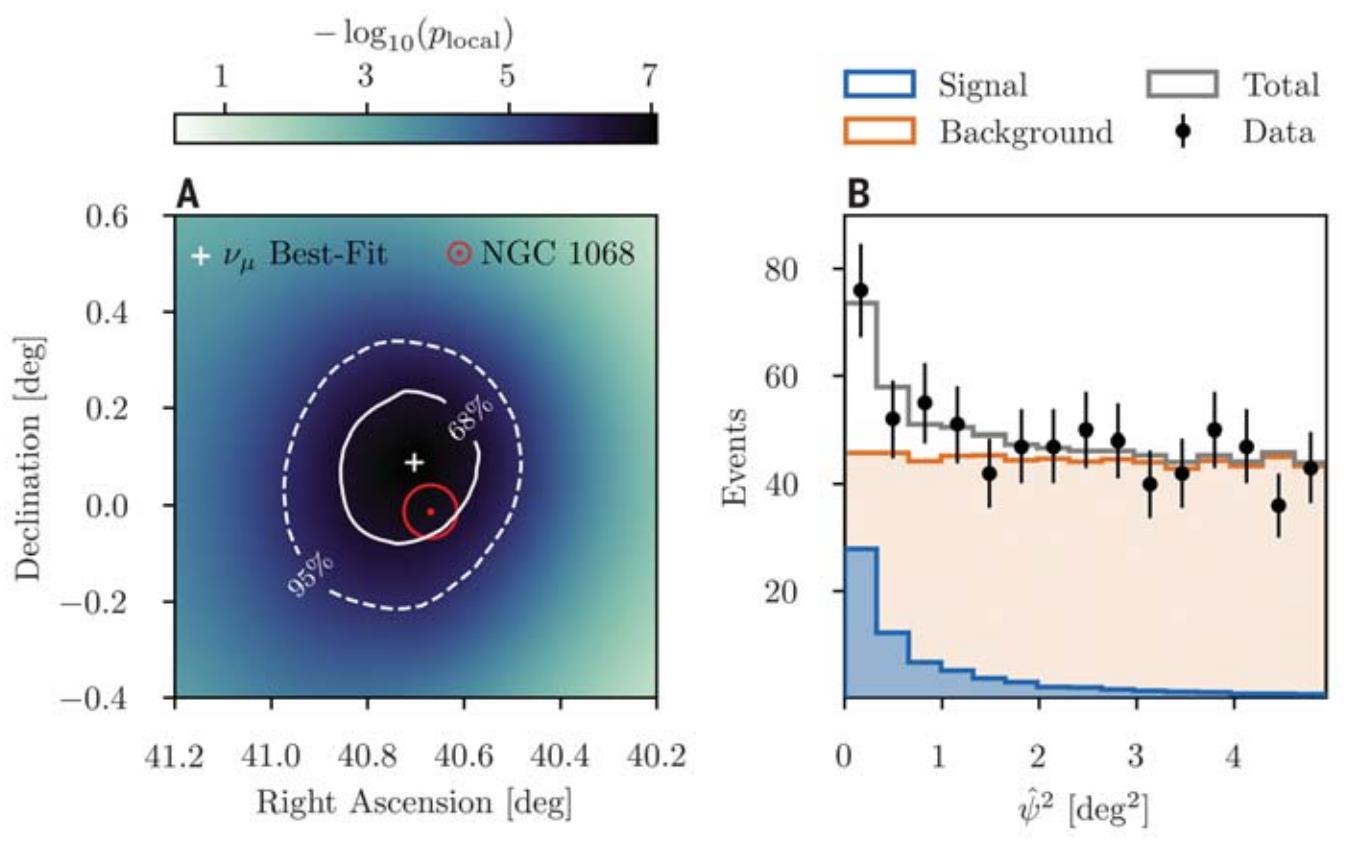

Today, if a core-collapse supernova went off within the Milky Way, it would be a safe bet that millions — and perhaps even tens or hundreds of millions — of neutrinos should be detectable from Earth. The physics that we expect to occur within core-collapse supernovae is understood, and hence, we can predict how many neutrinos should be produced and what their energy spectrum should be. Even though neutrinos oscillate, changing from one species to another as they interact with matter along their journey from being generated in the heart of a dying star until they arrive at our detectors, we can account for that.

We can precisely predict how many neutrinos should create a signal in our detectors from each species (electron, mu, and tau) based on measurable, observable parameters, including the mass of the star that goes supernova and the distance to the event. In other words, there’s an explicit prediction for how many supernova-based neutrinos we’d expect to detect, flavor-by-flavor, for any core-collapse supernova that occurs, including a prediction for what the energy spectrum of those neutrinos ought to be. That is, based on the physics we know, we have an expectation for how many neutrinos to expect from a core-collapse supernova no matter where it occurs, and that simply by observing the electromagnetic radiation and how it behaves as a function of time (i.e., the supernova’s light curve), we can infer what those neutrino observations ought to be.

And that’s where the exciting part comes in: the observations and our predictions won’t necessarily match, and if they don’t, that could provide a huge clue about the nature of dark matter.

Back in the 1960s, when we first started measuring neutrinos from the Sun and began comparing them with our predictions, we noticed a problem: there was a deficit from what was expected. We were only observing about a third of the neutrinos that we predicted we ought to see, creating a longstanding puzzle. Eventually, we realized that even though the Sun was producing 100% electron neutrinos from its interior nuclear reactions, by the time those neutrinos interacted with our detectors, they had oscillated into the other two species (or flavors) of neutrino: muon and tau neutrinos. Only once neutrino oscillation was understood — which required becoming sensitive to detecting at least one of the other species — was the puzzle able to be resolved.

But now, armed with an understanding of both neutrino production and neutrino oscillation, we should truly be able to predict how many neutrinos should arrive from a core-collapse supernova occurring within the Milky Way. Of course, those predictions assume that our Standard Model represents all of reality, and that core-collapse supernovae proceed according to the rules of particle physics that we know of today. Is that going to be representative of all the physics that actually exists? It can’t be; there’s also dark matter and dark energy in our Universe, and they’re not accounted for by the Standard Model at all.

Therefore, we have to consider the possibility, because it’s a prediction that’s never been tested, that perhaps dark matter is carrying some of the energy away from a supernova: energy that we currently expect would be carried away by neutrinos alone.

The nuclear reactions at the heart of a core-collapse supernova all occur under physical conditions — pressures, temperatures, and densities — that have never been produced in a laboratory here on Earth. Even though we have theoretical predictions for the particle physics interactions that we expect to occur, measurements from heavy ion colliders (such as RHIC and the LHC) can only tell us what occurs in the regime where data exists. Even though we expect that nature won’t show us evidence for any “new physics” when it comes to core-collapse supernovae, physics and astrophysics can’t rely solely on expectations. The only way to know for sure what nature has to say about the Universe is to make those key observations and measurements.

In particle physics, we’ve long searched for ways that dark matter might carry energy away from certain types of reactions, including via what physicists call an extra “invisible” decay channel. Those invisible decays have been sought in the lab for a very long time, but no one has seriously applied that same line of thought to the messy astrophysical environments that result in the production, in the final moments of a massive star’s life, of either a neutron star or even a black hole.

Under the extreme conditions of a core-collapse supernova, the possibility that we could observe a neutrino deficit holds wonderful implications for physics beyond the Standard Model. After all, 99% of the energy in a core-collapse supernova is expected to be carried away in the form of its neutrino signal. If even a small percentage of that energy is carried away by dark matter instead, an observed neutrino deficit could not only point to dark matter, but would significantly inform which types of future experiments might finally detect it directly.

All of this assumes, of course, that the Milky Way’s next supernova:

- will occur when our neutrino observatories are active and taking data,

- will indeed be of the core-collapse (type II) variety,

- and will occur at some point in the next few decades,

although none of those assumptions are necessarily true. Across the Universe, core-collapse supernovae are far more common than the other types, but the ones that have occurred in recent history in our own galaxy suggest that we might be experiencing more type Ia supernovae as a fraction of the total than the rest of the Universe. If our next supernova isn’t of the core-collapse variety but is instead a type Ia, it would have to be located within a few thousand light-years for us to be able to detect any sort of neutrino deficit.

If you were a betting person, when the Milky Way’s next core-collapse supernova occurs, the smart money would be to bet against any new physics, instead favoring behavior in accord with exactly what the boring old Standard Model predicts. However, when you’re searching for any signals of what might lie beyond our current picture of reality, you have to look to details that have never been probed before. No matter how it turns out, we can be sure that our galaxy’s next supernova will provide a wealth of information unlike any data we’ve ever collected before. We just need to make sure, when that key data arrives, that we keep our minds open even to the wildest of possibilities. If a neutrino deficit is part of the story, it could provide the greatest clue of all-time toward uncovering dark matter’s nature directly!

This article was first published in January of 2023. It was updated in November of 2024.