Pluto’s Color Variations Finally Make Sense

Why are some areas redder than others? It’s what happens to methane ice in the Sun.

“This is in a real sense the capstone of the initial missions to explore the planets. Pluto, its moons and this part of the solar system are such mysteries that New Horizons will rewrite all of the textbooks.” –Alan Stern

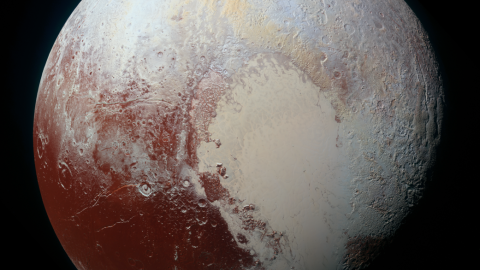

When viewed in enhanced color, the icy, outer world of Pluto looks very different from its more uniform, subdued hues.

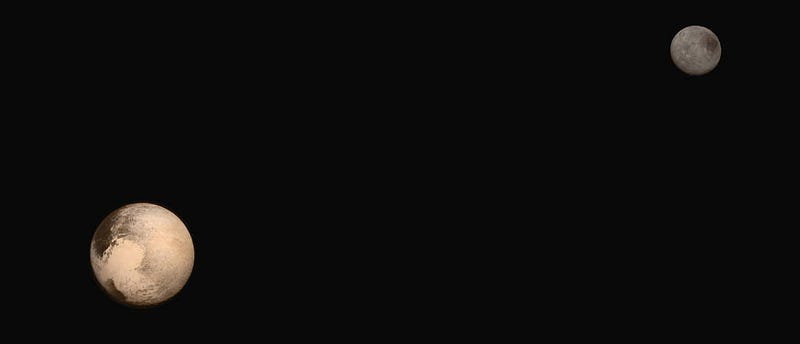

In natural color, Pluto is reddish while Charon is a dull grey.

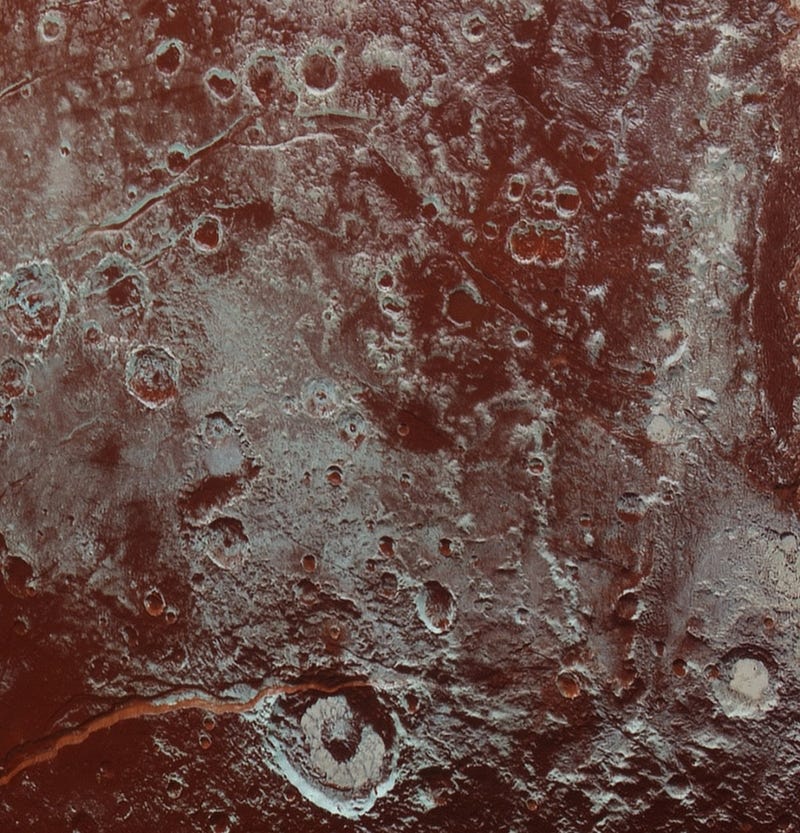

But the enhancements shows the presence of reddening in various regions all across the planet.

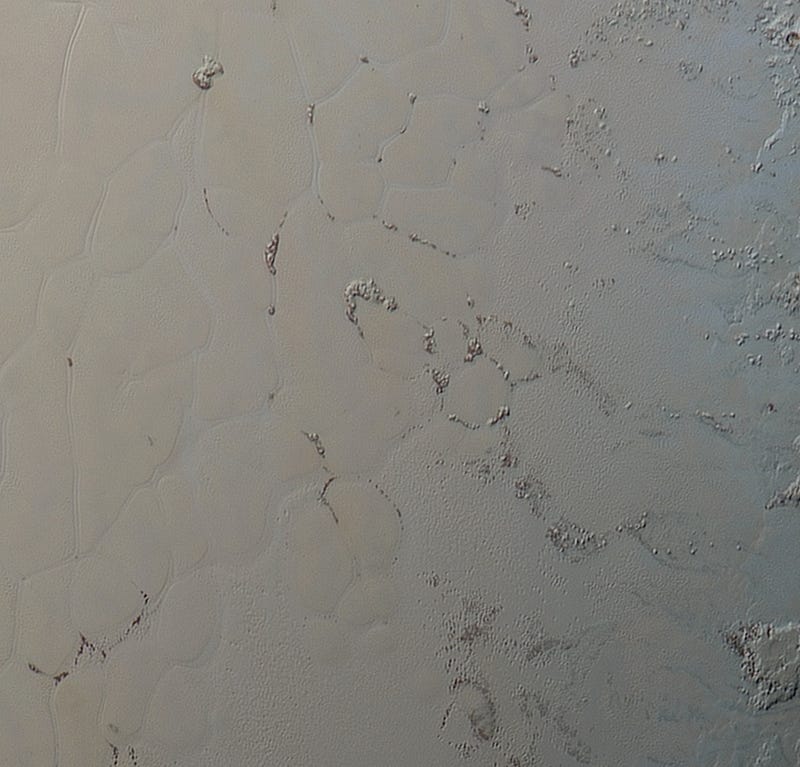

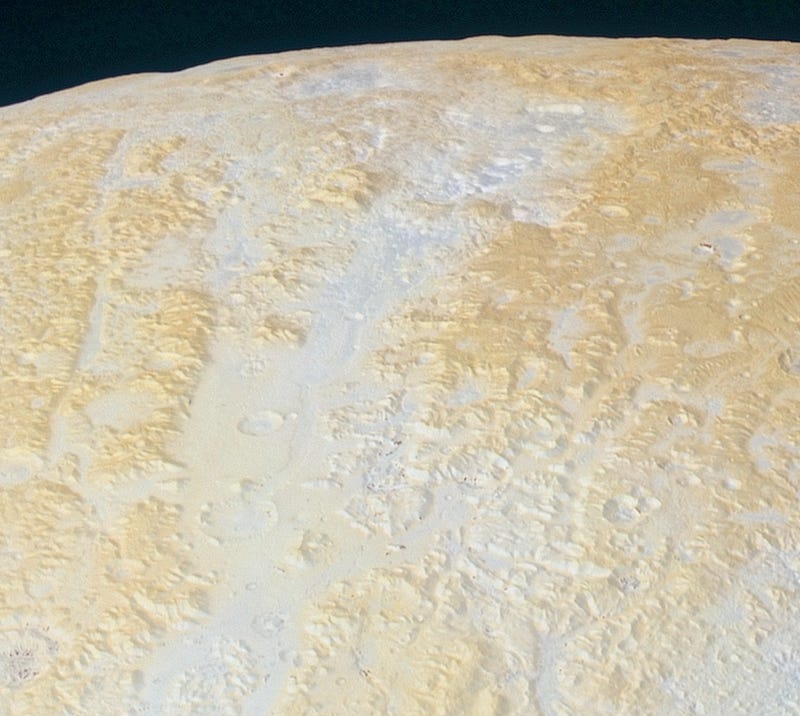

The hilly plains in Pluto’s heart-shaped area are mostly uniform, as a flat surface of nitrogen ice is disrupted by water-ice mountains and evaporative pits.

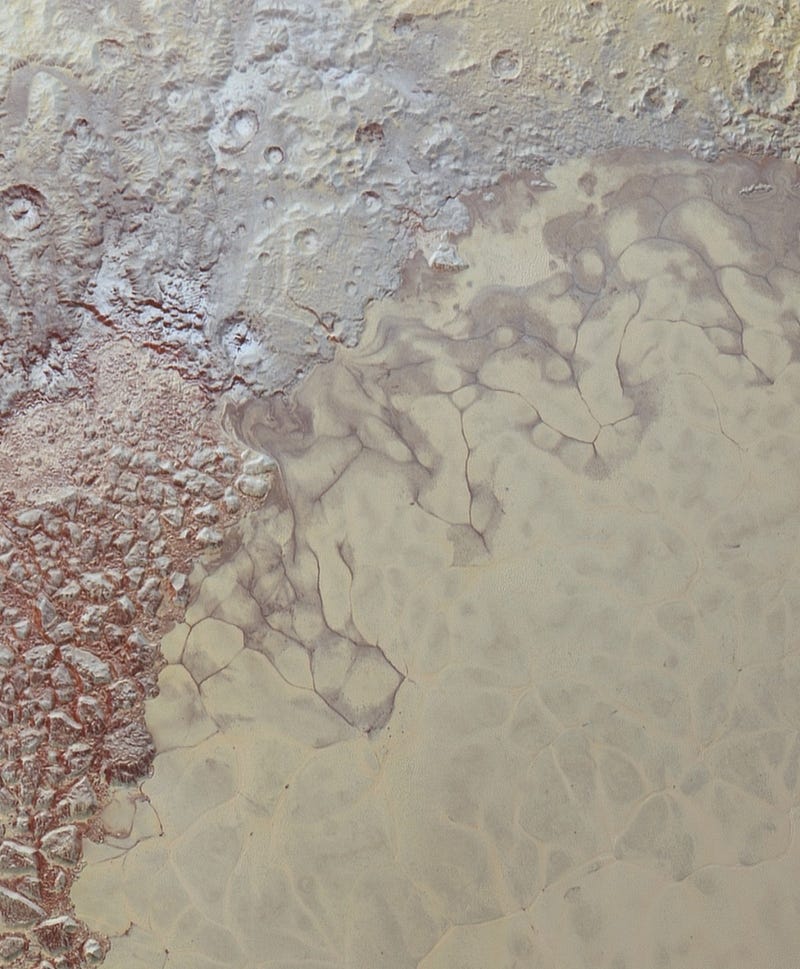

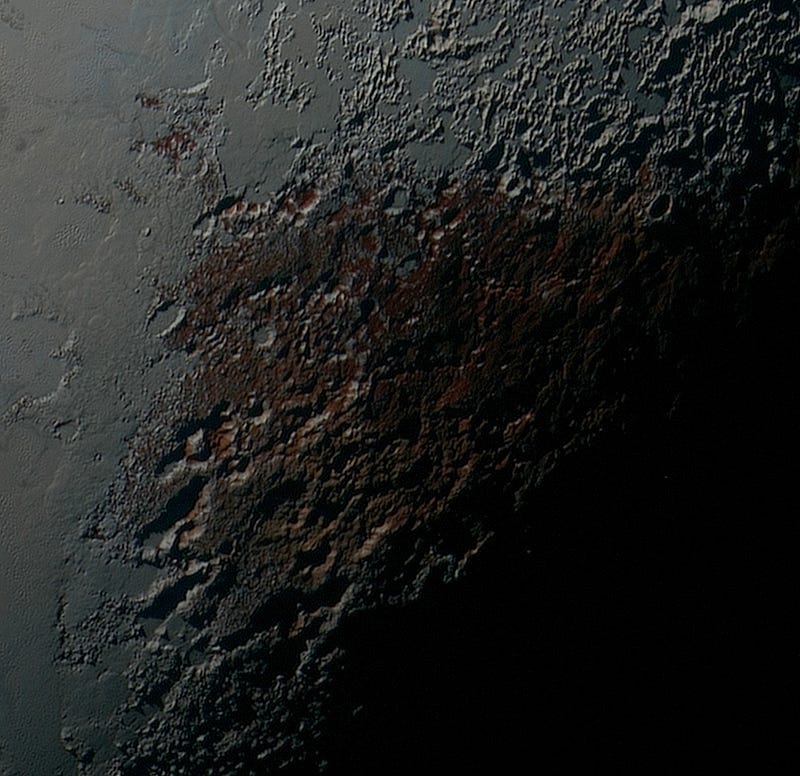

The more mountainous regions on the outskirts of the heart show subtle variations in both terrain and color.

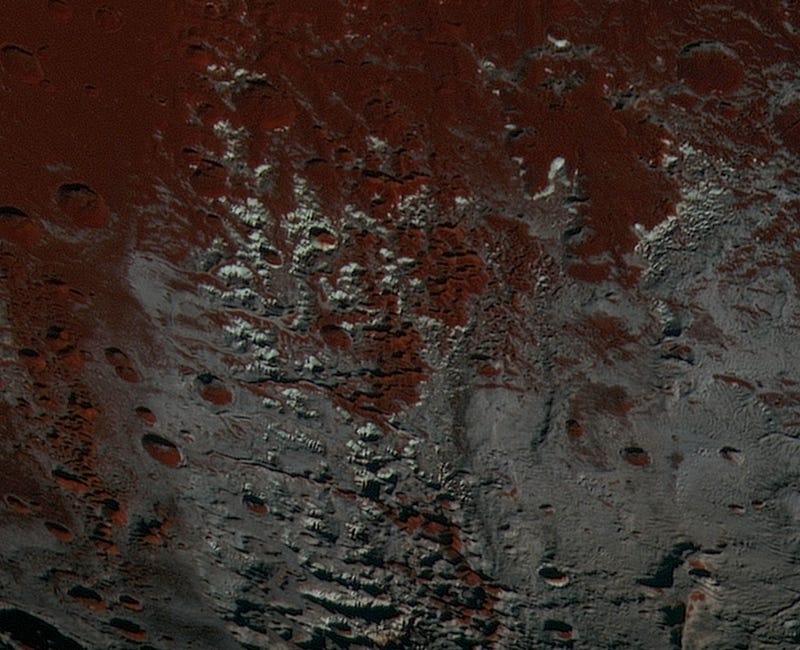

Huge variations are showcased at the interface of these two regions, as icy mountains transition into a smooth, nitrogen sea.

But the biggest variations can be seen where craters exist along mountain ranges. While nitrogen and water can both sublimate in the sunlight, the methane ices react differently.

The ultraviolet sunlight ionizes methane, setting off a chain of events that creates tholins — red-colored hydrocarbon compounds — that get deposited at various locations.

It’s only where fresh, white methane snow covers the tholin-rich regions that a white color reappears.

The next time we visit Pluto, this world’s colorscape will appear very different.

Mostly Mute Monday tells the story of a single astronomical object or phenomenon in pictures and visuals, with no more than 200 words of text.

This post first appeared at Forbes. Leave your comments on our forum, check out our first book: Beyond The Galaxy, and support our Patreon campaign!