The burden of proof

If a scientific theory can never be “100% proven,” how can we know what’s true?

“Never waste your time trying to explain who you are to people who are committed to misunderstanding you.” –Dream Hampton

Perhaps no word in the English language generates as much misunderstanding as the word theory. In scientific circles, this word has a very specific meaning that’s different from everyday use, and — as a theoretical astrophysicist myself — I feel it’s my duty to help explain exactly what we mean when we use it.

And in this particular context, I want you to think about the claims that because a scientific theory can never be 100% proven, we can never know for certain whether it’s true or not. Is it wrong to say something isn’t, therefore, real or true because we don’t have 100% proof?

Let’s consider this. Let’s start by thinking about how impossible it is to, for example, prove a negative.

This does not mean that all things ought to be taken as true, even in the absence of evidence.

What this sentiment echoes — from a scientific perspective — is that if you want to validate or invalidate a theory, you have to put the explicit-and-unique predictions arising from that hypothesis to the test.

But let’s back up a little more and define what I mean by theory, because when I use that word, I mean something very particular, and it’s likely different from what you think of when you use it.

At the very beginning of knowledge, you have straightforward facts about our reality. If I set up a system in a particular way, make a certain measurement using a specific method and/or set of tools, I will get a result. If I repeat that experiment many times, I’ll get a set of results. And if I look at the results of similar phenomena, experiments and/or natural occurrences as they’ve occurred many times, I’ll have an even more valuable set of data.

That’s the beginning of knowledge.

And then we apply our minds to that raw data, and we notice things.

When you take a sealed balloon filled with air and you submerge it deep underwater, its volume decreases. But it decreases in a particularly quantitative way: if you double the pressure around it, the volume it takes up halves. Noticing those types of relationships — or the empirical correlations between different parameters-and-variables in a system — is what leads to a slightly more advanced state of scientific knowledge, the formulation of scientific laws.

Scientific laws can tell you what’s going to happen under certain conditions, but they haven’t yet advanced to the point of a scientific theory. You see, a scientific theory is even more advanced than this, and posits an explanation and/or a mechanism from which scientific laws arise. And that’s where science can really show off its true power.

You see, as the generations pass, living organisms give rise to subsequent generations of living organisms; that’s data.

Those organisms are different in measurable ways from their predecessors; that’s the scientific law of evolution.

But the mechanism behind it — that organisms have the information for their traits encoded in their DNA, that DNA mutates and (in the case of sexually reproducing organisms) combines from two parents to form an offspring’s genetic makeup, and that the least fit organisms for survival are selected against, naturally — that’s a scientific theory.

Scientific theories are the deepest and most powerful explanations of how a scientific process takes place. The germ theory of disease is a theory; biological evolution is a theory; the atomic (and subatomic) theory of matter is a theory; and the theory of gravity is a theory.

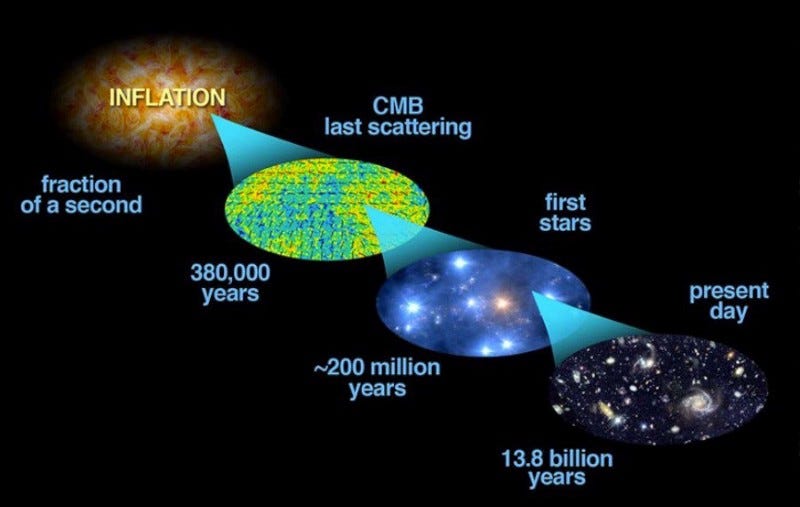

Still, after all that, there never is 100% proof of a theory. Even a hundred million successful tests and observations cannot prove a theory; they can validate a theory, they can demonstrate the robustness of a theory, but a single irreconcilable, reproducible observation is enough to show that a theory is not correct in all regimes, everywhere. This is likely true of all theories, by the way: that they have a range-of-validity, and outside of that range their validity breaks down.

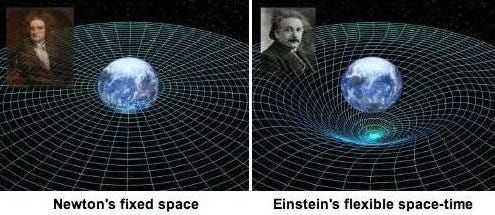

Newton’s laws of gravitation are fantastic over a huge range of applications, but their validity ends when confronted with very large gravitational fields, very small distances and speeds very close to the speed of light. As is often the case, it was superseded by an even better theory: Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, which both includes Newton’s range of validity and extends it to these special cases. (Although Einstein’s theory, too, has limits.) Attempts to extend Einstein’s theory are currently active areas of research, although it would be better for us all if we correctly called these attempts hypotheses right now, and only promote them to theories if they are, in fact, validated by experiments and observations.

But that does not mean everything posing as a scientific theory has validity behind it, or is worth considering seriously.

You need the data to support the foundations of your reasoning. You need the laws and correlations to build your theoretical framework atop them. You need a hypothesis or an idea of how it all fits together and can be explained by (relatively) simple principles. And finally, only if you have multiple lines of evidence and multiple tests and confirmed predictions, can you begin to rightly call your idea a theory.

Of course it’s wrong to say “just because we lack 100% proof doesn’t mean it can’t be true or real.” Some of the best theories we have today have outstanding predictions that have yet to be confirmed: the theory of General Relativity predicts gravitational waves, which we haven’t directly detected (yet); the theory of Dark Matter predicts the existence of new particles in the Universe, which we have not detected in terrestrial laboratory experiments (yet); the theory of abiogenesis predicts that life originates from non-life, although we have never once created life from non-life ourselves (also yet).

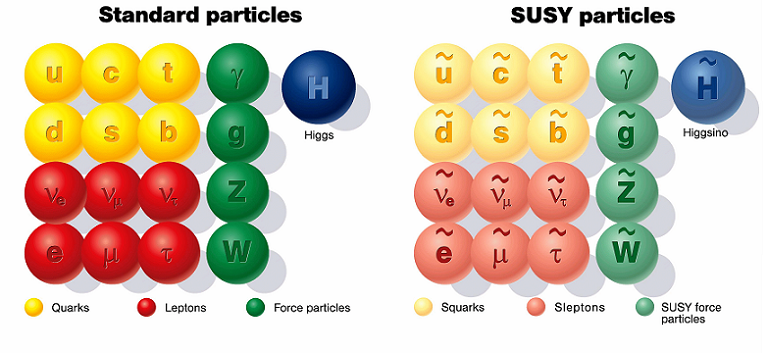

The burden of proof for an idea to get promoted to a scientific theory is tremendous, as even the vaunted Supersymmetry (and, in connection with it, String Theory) should be rightly referred to as a hypothesis and not a theory, as the evidence, successful tests and confirmed predictions still have not arrived.

So although it’s true that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, there is a burden of proof that must be met before we’re willing to promote an idea or hypothesis to the status of scientific theory. Once we’re there, however, we take the predictions of that theory very seriously, and are willing to consider not only the possibility but the probability that those new predictions — even the ones for which we do not yet have evidence — might be correct, no matter how assumption-challenging they may be.

It’s not 100% proof. It’s always open to refinement and improvement, and in that sense, it’s even better.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!