The Physics Of The Perfect Chocolate

With Valentine’s Day in the past, that’s no reason to forget about the best part of that holiday!

“Look, there’s no metaphysics on earth like chocolates.” –Fernando Pessoa

One of the most delectable treats for Valentine’s Day is the simple and elegant chocolate, which can be shaped into a variety of confections and combined with any number of sweet, salty or even savory flavors sure to delight even the most sophisticated of palates. The rich, creamy, shiny-smooth flavor and texture of a perfectly prepared chocolate is unlike any other culinary delight in all the world. Yet if you’re not careful, your chocolate could wind up a disaster in any number of ways:

- it could be crumbly in texture,

- it could have “lumps” or a graininess to it rather than a silky smoothness,

- it could be dull or waxy in appearance,

- or perhaps worst of all, it could get that gross white coating on the outside, known as chocolate bloom.

But all of these pitfalls are avoidable with a little bit of science. By looking at the physics of chocolate, we can understand exactly how these imperfections happen, how to avoid them all, and how to coax our chocolate into doing exactly what we want. If we understand the science behind it, we can take care and get a perfect chocolate each and every time, but you must not let those who don’t know what they’re doing contaminate your batch.

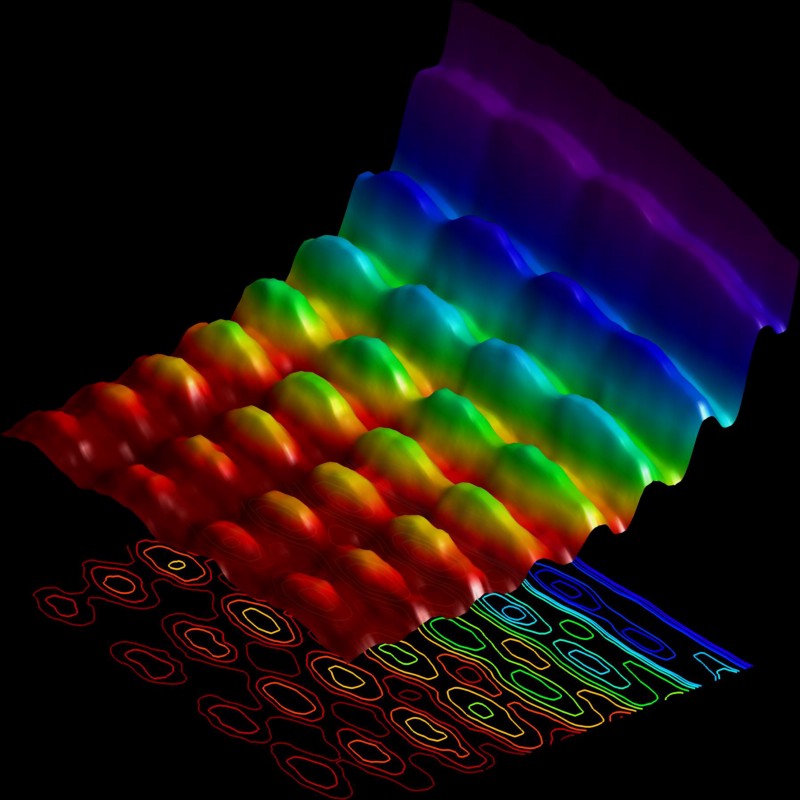

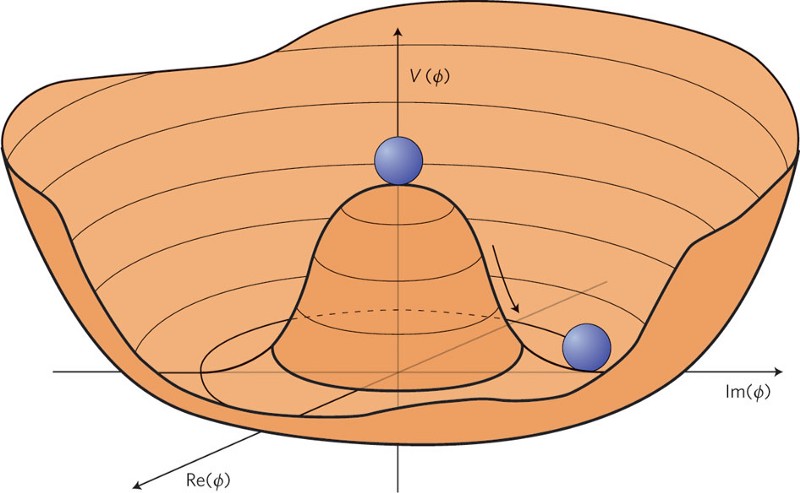

The first thing to understand is that chocolate, like carbon or ice, can form crystals in a number of different fashions. While carbon can form diamond, graphite, nanotubes, buckminsterfullerenes or even pencil lead depending on how it bonds together, chocolate can take on six different distinct crystalline structures, depending on how the chocolate molecules assemble next to one another. If you want to sound fancy, this means that chocolate is a six-phase polymorphic crystal. The chocolates that delight us most — the silky-smooth, creamy-textured chocolates — have their fatty acids from the cocoa butter (triglycerides) form into the fifth state: β(V). [The others, that you don’t want, are β(I) through β(VI).] There are two ways to make this happen: the universal way and the… well, the cheating way.

You’ll always want to use a good quality chocolate, which means a chocolate that’s about 60–70% cocoa butter, that contains cocoa solids, is low in sugar, is devoid of wax and other additives, and — and this is very important — that isn’t wet in any way. What you can do to any form of chocolate (the universal solution) is to heat it up in a double boiler to 130 degrees Fahrenheit, which will destroy all of the pre-existing crystalline structures. Then let it cool down to 80–82 degrees while still keeping it in its liquid form: this allows the β(V) structure to form, but the β(IV) crystals can’t exist. The texture will seem weird, a little sludge-like and hard to work with, so you can bring it up a little bit to about 90 degrees, but no hotter, or you’ll have to start over. 90 degrees is right on the border between where β(IV) and β(VI) crystals can form, but if you don’t overheat it, the chocolate molecules will line up in a long, straight pattern, producing a smooth, silky, shiny texture when you cool it slowly. Keep stirring it while it cools, while you’re creating your finished confections, and it will not only retain that awesome texture throughout, but you’ll be left with a creation that looks as beautiful as it tastes.

Even like this, it won’t last forever, since the β(VI) crystal is more stable than β(V), and so if you store your chocolates for months or more, they’re likely to get that dreaded chocolate bloom on the surface. But this is hard, requires practice, and is often very difficult to execute. Even many of the top-of-the-line commercial chocolates fail, as a scanning electron microscope reveals.

Instead, it’s much easier to melt your chocolate, cool it down just a little bit, and then add in some seed chocolate that’s been properly tempered. This is actually easy to get: it comes in wafer-like disks called chocolate fèves, and they start with the right crystalline structure, β(V), right off the bat! Much like most crystals, they’ll cause whatever liquid they come in contact with to assume the same crystalline structure, meaning that if you have unstructured chocolate, even as the chocolate fèves melt, they’ll impart that β(V) structure throughout your mixture!

And if you do it right, you’ll end up with the perfect science-based chocolates. This method has been physicist-tested and approved, as University of Washington’s Julianne Dalcanton can attest:

Last weekend I made the wedding cake above for the same solid state physicist who made mine a decade ago… Making the thin chocolate sheets from which I cut the decorations, I got huge swaths of perfectly glossy chocolate. Occasionally, though, there’d be a small section with a matte surface, that was clearly a different crystalline form.

If you want to make your own, delicious chocolate treats, this is the way to do it, and you’ve got science to thank for it. If you do it right, your tastebuds — and perhaps anyone you’ve got your eye on for next Valentine’s day — will thank you, too.

This post first appeared at Forbes. Leave your comments on our forum, check out our first book: Beyond The Galaxy, and support our Patreon campaign!