The Stamp that Almost Caused a War

War is terrible, but the causes of war are sometimes laughably trivial. Central America seems to have a special knack for silly casus belli. In 1969, El Salvador and Honduras fought a four-day conflict popularly called the Football War, after the contested soccer games that lit the fuse of ongoing animosity between both countries. In 2010, Nicaragua and Costa Rica came within inches of fighting a war caused by Google Maps [1].

But it gets sillier: in 1937, Nicaragua and Honduras almost came to blows… over a stamp.

In August of that year, the Nicaraguan postal service released a new set of Air Mail stamps, centred on a map of Nicaragua. The map also showed part of Honduras, north of the border, in the same shading as Nicaragua proper. Altough the accepted border between both countries was also shown, the part of Honduras shaded as Nicaragua was labelled Territorio en Litigio (‘Territory in Dispute’).

The Honduran territory in question had indeed once been claimed by Nicaragua, but Honduras thought the matter had been settled in 1906, when an arbitration by Spain’s king Alfonso XIII had awarded it the area.

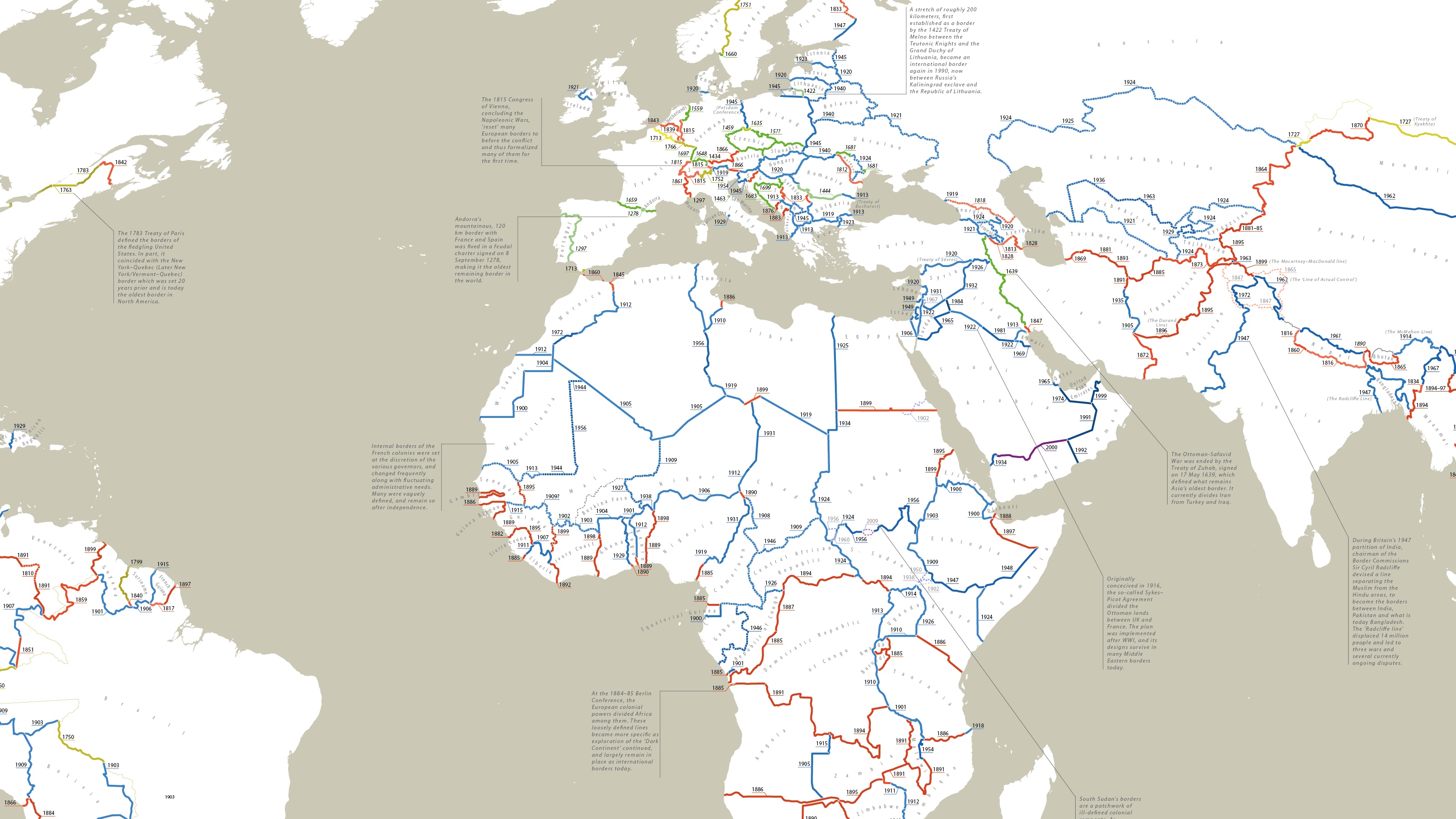

The roots of the problem lay in the chaotic genesis of the Honduran-Nicaraguan border. Central America’s baby steps after independence from Spain in 1821 were as a united, federal republic. After a few years, it turned out the centrifugal forces were too great, and the former Spanish provinces struck out on their own.

At that time, Honduras and Nicaragua agreed their common border should be determined by the principle of uti possidetis [2]. Not an easy task, as it turned out – the border region had been thinly, and often unsuccessfully settled, making it difficult to ascertain how far the authority of the former Spanish provinces reached.

In 1894, the two neighbours agreed to the only logical course of action: a Mixed Boundary Commission, tasked with demarcating the border from the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts. Compounding the difficulties of terrain and climate was the unfortunate coincidence that the (vaguely defined) border region lay across where the Central American isthmus is widest.

In 1900, the Commission produced its findings – establishing a border along straight lines, riverbeds and mountain ranges from the Pacific to a place called Portillo de Teotecacinte. Alas, this was only one third of the eastward distance to the Atlantic. The Commission wasn’t able to unmix its feelings about the remaining two thirds of the border.

Cue king Alfonso XIII of Spain, called in to dispense Solomonic justice [3] – a logical choice, as the former colonial power was both knowledgeable and disinterested in the conflict. Alfonso ruled on 23 December 1906 – providing Honduras with an early Christmas gift: the Rio Coco [4] was chosen as the eastern border with Nicaragua, all the way to its estuary at Cabo Gracias a Dios [5], depriving Nicaragua of a large chunk of disputed territory.

Although Nicaragua at first seemed to accept the Spanish king’s ruling, it later challenged its validity – thus creating an accident in waiting. That accident almost happened in 1937, with the issue of this stamp. Philately is a tried and tested means for countries to vent their irredentist feelings [6], and Nicaragua contributed its 10 centavos by surreptitiously reawakening its claim to the area north of the Rio Coco.

The Honduran reaction was particularly violent, and unforgiving. When the first airmail letters from Nicaragua bearing the offending stamp reached the Honduran capital Tegucigalpa, riots erupted. Honduran police had to make great efforts to prevent an angry mob from storming the Nicaraguan Embassy [7]. As Honduras demanded Nicaragua retract the stamps, both countries started sending troops to the disputed border region. It took mediation by the US, Mexico and Costa Rica for the threat of war to recede.

The conflict returned to its unresolved status quo until, in 1957, under the auspices of the Organization of American States, Honduras and Nicaragua again submitted their dispute to arbitration – this time to the International Court of Justice in The Hague. At the end of 1960, the ICJ reaffirmed Alfonso’s initial award – thus finding in favour of Honduras. Another Mixed Boundary Commission now finished the work of the first one, fixing the 573 miles of land border between both countries.

In the 1970s and especially the 1980s, both countries again teetered on the brink of war, this time over maritime borders – but that’s another story [8] …

________

Strange Maps #581

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] See this article of the Borderlines series.

[2] In full: uti possidetis, ita possideatis. Meaning: ‘As you possess, you shall continue to possess’. A method of settling territorial disputes by agreeing that each party hold on to the possessions currently under its control. Often used to justify conquest. The opposite principle is status quo ante, restoring the border to the ‘status before’ (hostilities).

[3] Foreign monarchs were often asked to arbitrate in border disputes. In the 1840s, the King of the Netherlands was asked determine the border between Maine and New Brunswick, then in dispute between the United States and Great Britain. See #106.

[4] At 465 miles, the longest river in Central America. A.k.a. the Segovia, Cape, Yara and Wanki River. For the entire text of Alfonso’s award, see here.

[5] So named by Columbus in 1502, who upon rounding it left a storm behind. He said: Gracias a Dios que al fin salimos de esas honduras. (‘Thanks to God we’re finally leaving these depths’); in the process not only naming the cape but also the future country.

[6] Also used in the past by Ecuador to bolster its claims on a large chunk of the Amazon basin. See here.

[7] The fragility of diplomatic immunity has sadly been proved again in recent days.

[8] See this link at the American Society of International Law.