Could South America be Atlantis?

Irrespective of whether it’s entirely mythical or merely missing, the ‘lost’ island of Atlantis is one of the most sought after pieces of real estate in history. The oldest source for the stories of a once mighty land now vanished beneath the waves are two of Plato’s Dialogues (4th century BC). But while Timaeus and Critias place Atlantis beyond “the Pillars of Hercules” (i.e. the Strait of Gibraltar) in the Ocean that still bears its name, evidence of Atlantis has been proposed and presumed in places as far apart as Sardinia, Antarctica, Cuba and Indonesia.

These days, most serious scientists prefer one theory over all others; that the drowning of Atlantis is a folk memory of a catastrophic volcanic eruption on the island of Thera (present-day Santorini) some time around 1600 BC that caused a tsunami, wiping out the Minoan civilisation. Many pre-modern scientists held to Plato’s original thesis, that Atlantis was once lapped by the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. One of them was Athanasius Kircher, who produced this map in his book Mundus Subterraneus (‘The Underground World’, ca. 1665).

A biography published in 2004 dubbed Kircher (1601-1680) was titled The Last Man to Know Everything, and the German Jesuit’s interests and expertise were certainly wide and deep enough to rival Leonardo Da Vinci’s. Both would be close contenders for the title of Ultimate Renaissance Man. Kircher wrote 40 books, on subjects as diverse as geology, music theory, Coptic grammar and magnetism (typically for his syncretic style, both of the gravitational and amorous kind).

Like Da Vinci, Kircher was fascinated by the invention and perfection of mechanical contraptions. He designed what has been described as the world’s first megaphone, perfected a magnetic clock and invented a cat piano, whereby a pin would pierce the tails of the animals which would then yowl at specific pitches (it’s not clear whether Kircher ever realised this scheme, although Monty Python in one of their sketches adapted the idea to a ‘mouse organ’). He is also credited with inventing the magic lantern.

That Kircher’s international fame was eclipsed by Rationalism later in his life may be understood from some of his more outlandish theories. Although still considered one of the founding fathers of Egyptology, he believed that Egyptian was so ancient that it must have been the language of Adam and Eve. Centuries before the hieroglyphs were deciphered, Kircher convinced himself that he had cracked the code, producing volumes of nonsense translations. An equally early pioneer of Sinology, Kircher thought the Chinese descended from Ham, and Confucius identical to Moses. In Arca Noë, he discussed the logistics – including the feeding schedules – of Noah’s Ark voyage.

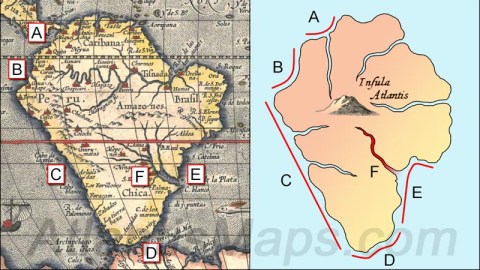

Mundus Subterraneus is a blend of vision and error typical of Kircher. He correctly postulates “fires” raging inside the earth, but links the tides to the interaction with an underground ocean. Included in the work is this map of Atlantis, placing the lost island (or rather mini-continent) between Spain and America. For some reason, the map is oriented upside down, with the south on top. The main island of Atlantis is accompanied by two smaller, unnamed ones to its right (west).

The Latin inscription reads: Location of the Island of Atlantis, long ago swallowed by the sea, according to Egyptian tales and the writings of Plato.

The story does not stop there, at least not if you’re a true Atlanticist – seeking truth where others see none. Some have remarked on the similarities between the shape of Kircher’s Atlantis and the geography of South America. Could it be that Plato was actually talking about that continent?

These two maps compare South America as shown in Ortelius’s Typus Orbis Terrarum (1592) with Kircher’s Atlantis (now oriented with north on top). The similarities are striking, from the double-scalloped coast in the northwest of the continent (A,B) over the long, straight coast of the southwest (C) and the narrowing tip in the south (D) to the recessed coastline in the east (E,F).

Another map goes even further, putting a name to half a dozen geographic similarities, including three of the continent’s major rivers (Amazon, Orinoco, Plata), two mountain ranges (Cordillera, Andes) and theorising that the smaller unnamed islands are actually the West Indies.

Looks and sounds plausible? Before you fall down the Atlantology rabbithole, check out this map comparison: Doesn’t Greenland also look a bit like Atlantis?

Oops… Too late! Bon voyage, fellow traveller!

Many thanks to Barry Ruderman for sending in the Kircher map. A larger-scale picture can be seen here on Mr. Ruderman’s Rare Maps. The website has a special section detailing many other antique print curiosities, both cartographic and otherwise. The lettered comparison map found here at Atlantis Maps. The labelled one found here. The Greenland image found here.

Strange Maps #394

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.