500 – It’s 10:15 in Germany. Do You Know Where Your Isoglosses Are?

Germans have a reputation for punctuality. Is that why they have so many ways of telling the same time? If it’s 10:15 in the germanosphere (1), you’ll have at least four options of expressing that particular moment. Those four options are all regional variants, so that, in German, you can tell with some degree of certainty which general area someone hails from by the way they tell the time at quarter past ten (2).

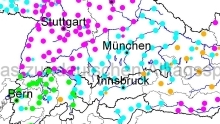

This isogloss map (3) shows that in a large part of north-western Germany, from the Danish to the French border, the preferred option is viertel nach zehn (‘quarter after ten’). This viertel is considered a fixed point in time, and its point of reference is the previous full hour.

Remarkably, the eastern boundary of this area is to a large extent identical to the former border between West and East Germany. It includes all or most of the German Länder of Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg, Bremen, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, Hessen, the Rhineland-Palatinate and the Saarland (as well as Luxembourg and the German-speaking area of Belgium).

In what used to be East Germany (4), the same clock time is referenced as viertel elf (‘quarter eleven’). This viertel is not a point in time, but a period of time, i.e. one-fourth of the next hour. This area doesn’t stop at the former German-German border, but extends into northern Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg.

An option limited to German-speaking Switzerland (5) is to call this particular time viertel ab zehn (‘quarter from ten’). Like the first viertel, this one is distanced from the previous hour by a preposition, albeit not a unidirectional one. In theory, this moment could both be before or after ten. Common usage will probably make such confusion improbable (although it would be interesting to know whether this option is as unambiguous for non-Swiss German speakers).

Another national Option is viertel über zehn (‘quarter over ten’), used only in central parts of Austria (5). In much of the rest of Austria, as well as in adjoining parts of Germany (southern Bavaria) and Italy (southern Tyrol), we see the recurrence of the north-western option, whereas the east and south of Austria repeat the East German option.

The recurrence of these ‘northern’ forms messes up any comparison of this particular isogloss map to a more general, composite map of German dialects, which usually draws two smoothly flowing lines east to west across the middle of Germany to distinguish between Low, Middle and High German (7).

Other isogloss maps at this page of the Philologisch-Historische Fakultät at Augsburg University show a similar diversity of geographic distribution for such concepts as Pfannkuchen (pancakes), Hefegebäckmann (a traditional German pastry in the shape of a person), and Hausschuhe (indoor slippers).

Many thanks to Leszek for sending in the 10:15 map.

——-

(1) the area where German is spoken; or, more precisely, where it has an official status: Germany, Austria, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Belgium and Italy. Analogous to anglosphere, but much less commonly used (621 vs. 90,500 Google hits; even less popular is germanophonia: 42 hits). Similar transnational linguistic circumscriptions include the Sinosphere, la Francophonie, and o Lusofonia (Portuguese-speaking nations).

(2) or ten-fifteen. I am not aware of whether this option in English is concurrent with a geographical differentiation.

(3) an isogloss map shows the geographical borders between linguistic features, be they related to syntax, semantics or pronunciation. They can focus on one particular element (like this time-telling one) or show the boundary between a complex of features (e.g. the borders between different dialects).

(4) now redistricted as the Länder Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Brandenburg, Berlin, Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony and Thuringia.

(5) or Deutschschweiz, if you’re more into consecutive consonants.

(6) almost only. There’s one yellow dot in Switzerland.

(7) the Benrath Line, from Düsseldorf to Frankfurt an der Oder, describing the isogloss between maken (to the north, Low German) and machen (to the south, Middle and High German); and the Speyer Line, separating northern dialects with a geminated stop from High German ones in the south with an affricate (Appel-Apfel). In between lies the Middle Germanlanguage area.