Cartography’s Favourite Map Monster: the Land Octopus

Over the centuries, the high seas have served as a blank canvas for cartographers’ worst nightmares. They have dotted the oceans with a whole crypto-zoo of island-sized whales, deathly seductive mermaids, giant sea serpents, and many more – a whole panoply of heraldic horrors. As varied as this marine bestiary is, mapmakers have settled on a single, favourite species for land-based beastliness: the octopus.

Real octopi are sea creatures, of course. But the Cartographic Land Octopus – CLO for short – need not worry about being in the right ecosphere. Being fictional, it is not restricted to the sea. It can (and need) do only one thing: instil map-readers with fear and revulsion. But the CLO’s pedigree does stretch back to the ocean. It is clearly descended from an older monstrosity, equally fictional but wholly sea-bound: the Kraken, a giant squid whose enormous tentacles dragged whole ships down to their watery graves.

I suspect it’s those tentacles that explain why the octopus became cartography’s favourite land monster. They turn the CLO into a perfect emblem of evil spreading across a map: its ugly head is the centre of a malevolent intelligence, which is manipulating its obscene appendages to bring death and destruction to its surroundings. This is perfect for demonstrating the geographic reach of an enemy state’s destructive potential. It can even be used on a more abstract level, showing dangerous ideologies insipidly infiltrating and/or strangling the world.

The Cartographic Land Octopus was born two-thirds into the 19th century, when the intra-European tensions were slowly gearing up towards the First World War; it flourished until the end of the Second World War. But it still maintains its grip on the cartographic imagination today, as will be shown towards the end of this concise timeline of CLO cartoons.

But before we get biographical, some categoric disentangling. As a graphic concept, the CLO overlaps with tow similar tropes. Firstly, the non-cartographic cartoon octopus (NCCO): like the CLO, this specimen is used to demonstrate the wide-ranging grasp of a particular evil, but unlike it, there is no map involved – even though all that grasping often implies a spatial element. Case in point are the popular depictions, in the late 19th and early 20th century, of monopolising, price-fixing business trusts like Standard Oil as destructive NCCOs.

Secondly, the anthropomorphic map. These show countries or continents in human shapes, either totally abstract, and mostly in the map margins (like the plump ladies symbolising the riches of Africa, Europa, Asia and America, seated in the four corners of antique world maps); or actually in the map, contorted to conform to the outline of the nations they represent (John Bull made to crouch like England, Marianne striking a France-shaped pose).

Anthropomorphism – and more broadly speaking, zoomorphism – had always been a fairly popular cartographic method [1]. The migration of the Kraken to land, somewhere around 1870, can be seen as an escalation, symbolising the hardening of international attitudes. The offending nation was refused the benefit of humanity, which would have allowed some primal empathy: even if Germany was represented by its loony Kaiser, it was still human, and thus not beyond redemption.

Perhaps as with spiders and other creepy crawlies, humans feel instant, instinctive and intense revulsion for the many-legged octopus. The CLO is aimed squarely at these feelings. Its aim is to signal: This is the primeval enemy, and it needs not just to be defeated, but to be destroyed.

Humoristische-Oorlogskaart (1870), from BibliOdyssey‘s post on satirical maps.

This Humorous War Mapmay well be the earliest traceable example of the CLO. It was produced in the second half of the 19th century by J.J. van Brederode in Haarlem, the Netherlands. It is one of many such maps circulating at the time across Europe, using the light-hearted medium of anthropomorphic cartography to illustrate the tense international situation. The map’s innovation was to show Russia not as its Czar (or, as also was quite common, the Russian bear), but as a belligerent octopus. The legend explains the contemporary geopolitical context of the map:

The Octopus (Russia, the great glutton) no longer thinks about the wounds received during the Crimean War, and advances its armies in all directions. After having stemmed the Turk’s advance, the Russian marches forward, hoping to crush Turkey like he did with Poland. It seems Greece is also desirous to occupy and exhaust Turkey from another direction. Hungary is restrained only by its sister Austria from attacking Russia. France, still smarting from its recent defeat, is studiously inspecting its arsenal. Germany is observing France’s movements, and is prepared for all eventualities.

Great Britain and Ireland are carefully monitoring the situation, and are prepared to prevent Russia from imposing itself on Turkey, or interfering in the Suez. Spain is taking a much-needed nap. Italy is toying with the Pope, while the rich King of the Belgians is securing his treasure. Denmark may have a small flag, but it has reasons to be proud.

Serio-Comic War Map for the Year 1877, here on Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.

The Brederode map is dated 1870, thus preceding Fred W. Rose’s nearly identical Serio-Comic War Map (1877) by several years. Yet it is the latter cartographer who is considered the great populariser of the anthropomorphic map – and the LCO. Rose in any case seems to have been more prolific, producing several variations on the Serio-Comic Map, and an updated version of it in 1900.

John Bull and his Friends – A Serio-Comic Map of Europe (1900), here on Livejournal.

Rose’s 1877 map is very similar to the 1900 one. But while Russia still is the offending protagonist, tentacling its way into its neighbours’ affairs, the nature and direction of some of the anthropomorphic nations has changed, reflecting an altered political landscape. Whereas France in the 1877 map is an old general aiming cannon at Germany, still frustrated by its recent defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-’71, France in 1900 is Marianne, dressed in the revolutionary colours, looking away from Germany, and toward Britain. A like-for-like comparison would lead us too far, but the legend of Rose’s 1900 map provides some explanation:

Great Britain – John Bull has been attacked by two wild cats. He is however able to rely on the stores of ammunition behind him, as well as his own pluck and great resources. The letter at his feet from his friend Uncle Sam, would be more encouraging were it not for the post-script. The Nationalist section in Ireland has taken this opportunity to vent his abuse upon him, but is restrained by the loyalty of the people.

France too, is scolding and threatening to scratch with one hand, while with the other she is beckoning on Germany to help her. Although the Dreyfus affair is thrust into the back-ground she is much occupied with her new doll’s house. She has somehow managed to break all the toys on her girdle and her heart is sore, for she attributes these disasters to John Bull.

Holland and Belgium are also calling him unpleasant names.

Spain, weary with her recent struggles, remembers that John was in no way inclined to help her, and looks up hoping to see him attacked by some of her neighbours.

Portugal is pleased to think he holds the Key of the situation.

Norway and Sweden though still struggling to get free from their mutual leash, turn their attention to John’s difficulties, while Denmark is kindly sending him a present of provisions.

Austria and Hungary will be content with dreadful threats

Switzerland‘s satisfaction that her Red Cross has done good service, is marred by the news of John’s victories, which she is reading.

Italy alone holds out the hand of encouragement to his old friend.

In Corsica the shade of her great departed son is wondering why people don’t act, as he would have done, instead of growling and cursing.

Turkey, resting comfortably on his late foe Greece, is smiling at the thought that these troubles do not harm him and perhaps he is not sorry that John will not come to much harm.

Russia, in spite of the Tzar’s noble effort to impress her with his own peaceful image, is but an octopus still. Far and wide her tentacles are reaching. Poland and Finland already know the painful process of absorption. China feels the power of her suckers, and two of her tentacles are invidiously creeping towards Persia and Afghanistan, while another is feeling for any point of vantage where Turkey may be once more attacked.

A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia (1904), here on ffffound!

This map, published in 1904, is an interesting, non-western take on the LCO. It was produced by Japanese student Kisaburo Ohara at the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War. The text box on this Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia reads:

‘Black Octopus’ is the name newly given to Russia by a certain prominent Englishman [i.e. Fred W. Rose]. For the black octopus is so avaricious, that he stretches out his eight arms in all directions, and seizes up every thing that comes within his reach. But as it sometimes happens he gets wounded seriously even by a small fish, owing to his too much covetousness(sic). Indeed, a Japanese proverb says: “Great avarice is like unselfishness.” We Japanese need not to say much on the cause of the present war. Suffice it to say, that the further existence of the Black Octopus will depend entirely upon how he comes out of this war. The Japanese fleet has already practically annihilated Russia’s naval power in the Orient. The Japanese army is about to win a signal victory over Russia in Corea & Manchuria. And when… St Petersburg? Wait and see! The ugly Black Octopus! Hurrah! Hurrah! for Japan.

Where Rose’s octopus spread its tentacles only on the western edge of the Russian empire, this Japanese version aptly illustrates the true, bi-continental nature (and reach) of this giant country. In Asia, it is reaching across China via Manturia (sic) into the Yellow Sea near Korea – where the Russians maintained a naval presence at Port Arthur, the site of their great defeat in 1905 [5]. Three Asian tentacles are further engaging Tibet, India, Persia and Turkey – all part of the so-called Great Game, Russia and Britain’s struggle for dominance in Central Asia.

The Prussian Octopus (1915), here at the University of Toronto Map & Data Library.

Whether imperial, soviet or post-communist, Russia is a favourite subject of octopodal cartography. So was its near-namesake, Prussia. A CLO map of the German Empire’s core state was discussed earlier on this blog [2]. Here is another one, dated 1915. The rather comical head of this Prussian Octopus is centred on Berlin, and its tentacles are scraping together extra territory from the general neighbourhood.

“We do not threaten small nations,” declared the German Chancellor on December 10th, 1915: “we do not wage the war which has been forced upon us in order to subjugate foreign peoples, but for the protection of our life and freedom.” The pictorial map is a commentary on his words. It shows how Prussia has stolen one province after another from her neighbours and, like a baleful octopus, is still stretching out her tentacles to grasp further acquisitions. The territories included in the original Kingdom of Prussia are marked [dark grey]. The territories since absorbed to negotiation, force, or fraud are marked [light grey].

The list of provinces acquired by Prussia, each draped with a tentacle, reads:

The voracious Prussian octopus has a playmate to the south, although the Prussian tentacle around the Austro-Hungarian’s rather doleful-looking head might indicate that the two monsters are frenemies rather than BFFs. Be that as it may, the relationship between both octopi seems responsible for the spread of Austro-Prussian expansionism into the Balkans:

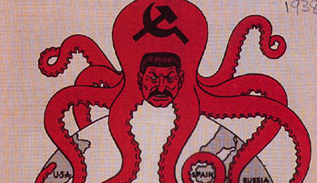

How Communism Works (1938), here at Vulgar Army.

The CLO need not necessarily symbolise a classic, territorial threat. Ideologies are easy targets for octopus-based propaganda: poisonous creeds have mental tentacles – invisible, and thus more dangerous. This stark, alarming illustration is the front page of a pamphlet by the Catholic Library Service (1938). It portrays communism as a hydra with the face of Stalin, and its tentacles curling around Spain (the Soviets had been heavily involved on the – losing – Republican side of the civil war), extending also towards the US.

Confiance… ses amputations se poursuivent méthodiquement (1942), here at the Victoria and Albert Museum’s digital collection.

The CLO itself is ideologically neutral, a gun for hire to each side of the argument. Here, we see the octopus used against the West. This propaganda poster, produced in 1942 by the pro-German Vichy government in France, shows Churchill as the head of a wounded octopus, its bleeding tentacles chopped off by the superior forces of the Nazi Axis. The locations evoked here are the sites of Allied military action against the Vichy-French, causing French casualties. The poster tries to rally French sentiment against the English – also by implying that the Anglo-American Alliance will use the war to steal the French colonial empire, a large part of which was situated in Africa. It also gives the impression that the war is going badly for the Allies, stating:Confiance, ses amputations se poursuivent méthodiquement (‘Have faith, [Churchill’s] amputations are progressing methodically’]. Just a matter of time before the Axis wins the war…

Erkenne die Gefahr! (1949), here at Vulgar Army.

The end of the war hardly means the end of the octopus. During the Cold War, great ideological chasms remain, large enough to fit a giant squid. In 1949, the conservative Oesterreichische Volkspartei exhorts Austrian voters with this poster to Recognise the danger! More words are unnecessary, the message is clear: the ominous, blood-sucking octopus advancing from the east is the spectre of communism, which has just gobbled up large parts of Eastern Europe [3].

Non! La France ne sera pas un pays colonisé! (ca. 1950), here at Vulgar Army.

Approaching from the opposite direction,both geographically and ideologically, is this American octopus, ready to devour France and all its Frenchness. This time, it’s the (French) communists appropriating the evil octopus trope for their political purposes.

United Underworld (1966), here at Indie Squid Kid.

The voracious hydra returns in self-parody rather than as geopolitical satire in a 1960s Batman movie with Adam West and Burt Ward as Batman and Robin. The Caped Crusader is facing a cartel of his four worst enemies (the Joker, the Riddler, the Penguin and Catwoman). This United Underworld has its own logo: an octopus strangling the globe.

Russia in 2008, here at Toon Pool.

The CLO made a full circle of sorts in 2008, when Graeme Mackay, a cartoonist for the Hamilton Spectator, a Canadian newspaper, updated the earliest octopus maps to show Putin again as a Russian hydra. In this period, a newly-resurgent Russia was reasserting its influence in the ‘near abroad’, i.e. those now independent republics that had been under Moscow’s sway until the end of the Soviet Union in 1992. By adapting a cartographic cartoon with a pedigree of over a century, Mackay proved the viability and adaptability of the Cartographic Land Octopus, which continues to stretch its tentacles across the globe to this very day.

Many thanks to all those who sent in octopus-based cartography, including Sarah Simpkin (the Prussian Octopus) and ArCgon (the Russian Octopi from 1877 and 2008).

Special mention should go to Vulgar Army, a fantastic website I discovered while researching this post. It’s dedicated specifically to Octopus in Propaganda and Political Cartoons, and is the source of many of the maps in this post. Check it out for extra helpings of maps and even more cartoons – all octopus-based. If it exists in the real world, there is a community obsessing about it in cyberspace: Vulgar Army’s blogroll refers to a dozen other websites devoted to octopi and other cephalopods.

Strange Maps #521

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

———

[1] Some examples discussed earlier on this blog: #141, #162 and #473.

[2] See #510.

[3] At that time, the Soviets were still occupying the eastern bit of Austria itself; Vienna was divided in Allied sectors much like Berlin. This may explain the wordless reference to the communist threat. The Soviets withdrew from Austria in 1955, on condition of the country’s enduring neutrality. The movie The Third Man (1949) provides an atmospheric sketch of the situation in ‘Four-Power’ Vienna.