The Road to Slimeville

It ain’t easy being slime. If you’re sticky and viscous, you’re going to be the gooey butt of persistent negative stereotyping. Slime-ophobia has been one long (and disgustingly dripping) thread throughout popular culture for the last half-century at least. Here’s a handful of movie references:

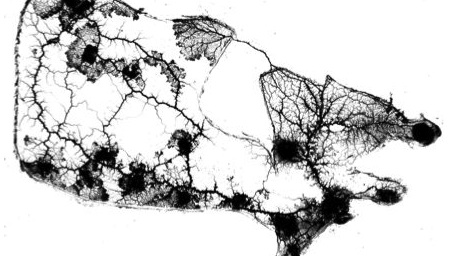

A slime map of America overlaying a real one, with proper roads.

What these movies tell us about our take on slime: it is mainly an epiphenomenon of evil. Goo underscores the evilness of evil. More goo, more evil.

Maybe the decades-long persistence of anti-slime propaganda stems from a fundamental human unease with our evolutionary antecedents. It took our species a few decades collectively to get over one of the evolution theory’s more shocking tenets – that we descend from apes [4]. Perhaps it’ll take us a few more to reconcile ourselves to the primordial ooze that we ultimately derive from.

These maps might help – showing slime in a more positive, relatable light: as a trailblazing entity with a human-like sense of purpose and direction. They illustrate a recently published scientific paper, entitled: Are motorways rational from slime mould’s point of view? [5]

Road China and Mould China: some remarkable parallels.

That description alone is a solicitation for an Ig Nobel Award [6], but the paper is more than merely a pretty title. It’s the product of serious research by the International Center for Unconventional Computing [7] at the University of the West of England in Bristol.

The ICUC has been investigating slime mould intelligence for some years now. The term ‘slime mould’ describes a fungus-like type of organism that basically is a collection of single-celled creatures. Despite their lack of a central nervous system, let alone a brain, slime moulds have demonstrated ‘intelligent’ behaviour in lab experiments. They can avoid obstacles, anticipate regularly reoccurring events, regulate food intake – and even seek to re-unite when cut in half.

Most of these experiments were conducted with Physarum polycephalum, a particularly clever slime mould [8], also used for the ICUC’s motorway trial. This is how it worked:

“Motorway networks of fourteen geographical areas are considered: Australia, Africa, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Iberia, Italy, Malaysia, Mexico, The Netherlands, UK, USA. For each geographical entity we represented major urban areas by oat flakes and inoculated the slime mould in a capital. After slime mould spanned all urban areas with a network of its protoplasmic tubes we extracted a generalised Physarum graph from the network and compared the graphs with an abstract motorway graph using most common measures.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, considering the slime mould’s previously demonstrated level of problem-solving intelligence, the protoplasmic networks in the Petri dish showed more than a passing resemblance to the motorway networks of the areas chosen. Say the researchers:

“We obtained a series of intriguing results, and found that the slime mould approximates best of all the motorway graphs of Belgium, Canada and China.”

The theory is that slime mould, despite not having a head for maps, for some reason is very good at finding the most efficient route to food. This then resembles the ‘organic’ growth of most road networks, which ultimately derive from ancient footpaths, chosen for that same reason: they represented the most efficient, least-obstacled route to food.

Route 66’s course through Missouri mirrors that of the Great Osage Trail, an ancient Indian path.

In mimicking that mindless, but efficient pathfinding process, Physarum polycephalum could possibly prove to be an interesting simulation tool for road builders. But the guys and girls over at the Center for Unconventional Computing are dreaming up even weirder stuff: physarum machines – programmable biocomputers with an organic intelligence. Proponents laud the cheap production and green credentials of such computers. Those not in favour have been surprisingly silent. Their rallying cry could be: The Triffids [10] are coming! And as ICUC’s motorway experiment shows, they’ll know how to find us…

Many thanks to Tien Ling, Marion Diamond and John O’Brien for sending in links to these maps (This article in the New Scientist, and this one at I09). The picture of the Great Osage Trail taken at the Meramec Caverns in Stanton, MO. Route 66 map taken here.

Strange Maps #558

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.

[1] Sticky and viscous.

[2] A subterranean race? Of slimy, lizard-like people? Under Los Angeles? Maybe not so fictional after all! See #443.

[3] In its original definition, a substance supposedly excreted by mediums during séances, sometimes described as slime-like, other times as misty or tissue-y. Later also any slime associated with any ghostly appearance or haunting.

[4] Not everybody is over it yet. Almost 90 years after the Scopes Trial (1925), the evolution theory and various guises of creationism are still doing battle over supremacy in the classroom, in the US and beyond.

[5] Complete paper here.

[6] The Ig Nobel Prizes have been awarded annually by the Annals of Improbable Research since 1991 in parody of more serious (or rather self-important) scientific prize-giving. A complete list of previous winners here.

[7] At the University of the West of England in Bristol. It’s so international that they mis-spell Centre.

[8] Perhaps because its name indicates that it has ‘many heads’. In spite of its supposed cleverness, it dwells mainly on forest floors and rotting wood. No attempt to hijack a meteorite has been reported. Yet.

[10] The large, mobile, carnivorous and lethal plants in John Wyndham’s science-fiction novel The Day of the Triffids (1951).