A Man, a Plan, a Canal: Karakalpakstan!

Karakalpakstan. The name sounds made up, but it’s a real place. And it could have been the 13th member of a fairly exclusive club: nations which have only a’s for vowels in their name. The others being the Bahamas, Canada, Chad, Ghana, Japan, Kazakhstan, Madagascar, Malta, Myanmar, Panama, Qatar and Rwanda. As the only country in the world scoring five a’s in a row, it would have ruled this particular roost.

Perhaps the God of Geography decided in his wisdom that this would just have been too much of an accolade for what is, essentially, a forlorn, windswept, ecodisaster-ridden corner of Central Asia. So Karakalpakstan (the name is Turkic for ‘Black Hat Land’, a toponym that also only has a’s for vowels – how weird is that?) continues its twilight existence, forever on the brink of brighter days (or darker nights) as both Uzbekistan’s geographically eccentric western outpost, and the only ‘autonomous republic’ of a medium-sized post-Soviet autocracy.

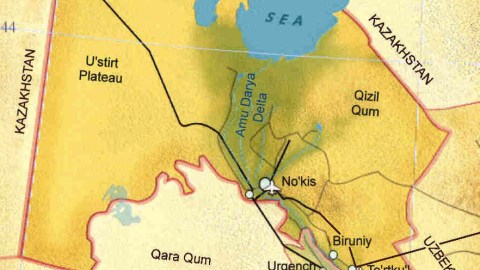

Karakalpakstan is much larger, and its borders much straighter than most other administrative subdivisions of Uzbekistan. Which reveals that this is the country’s most sparsely populated territory. And indeed, this Wisconsin-sized republic counts less than 2 million inhabitants (out of 30 million for Uzbekistan as a whole), mostly concentrated along the banks of the Amu Darya.

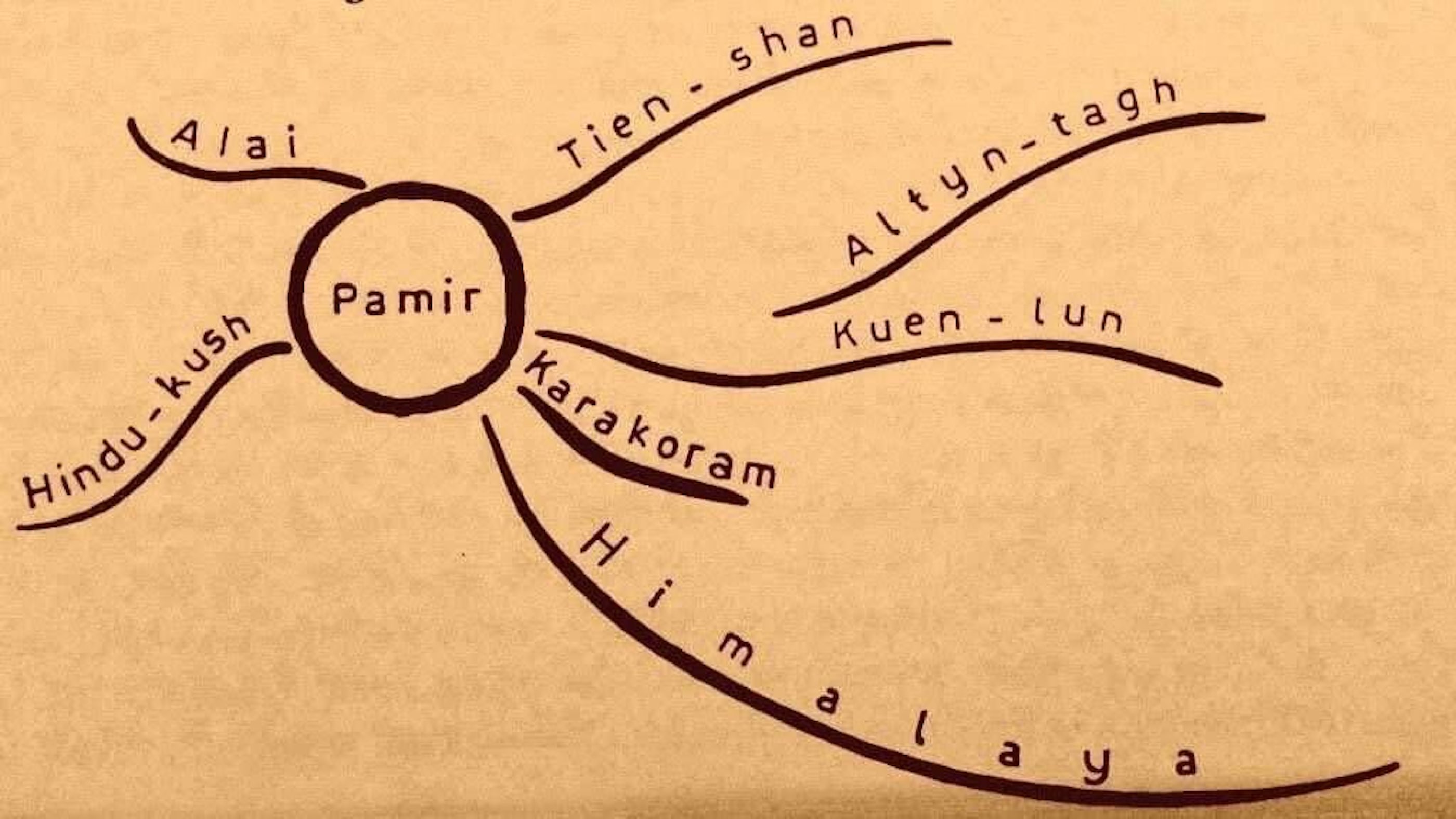

The fertile delta of that river is the only corridor connecting Karakalpakstan to the rest of the country. For the rest, the republic is desert: the red sands of the Kizilkum stretch to the east, the stony Ustyurt plateau to the west, the barren, blackened Karakum to the south, and the salt flats of the Aralkum to the north (you may have guessed that kum means ‘desert’ in the local lingo). Geopolitically, Karakalpakstan is wedged between the almost completely evaporated Aral Sea in the north, Kazakhstan to its east and west, and Turkmenistan, home to a bizarre personality cult for its dead autocrat, to the south.

Managing to be colossal, intricate and shoddy at the same time, a Soviet irrigation system of tiny ditches and grand canals meant to feed a monoculture of cotton has sapped the strength of the once-mighty Amu Darya. Known to Alexander the Great as the Oxus River, its waters until recently replenished the Aral Sea; but now it peters out in the desert sands, far from where fishing vessels lie stranded in the middle of the dunes, no longer lapped by waves that now seem as alien as water on Mars. The former lakebed is the birthchamber of countless toxic sandstorms plaguing the region, keeping local life expectancy in check.

Where the river still flows, further south, the city of Nokis (or Nukus) lies on its banks. The unassuming Karakalpak capital, a Soviet new town formerly home to the Red Army’s research labs and testing sites for chemical and biological warfare, is remarkable only for the dust devils that poison its inhabitants, and for the Savitsky Museum, the world’s second-largest collection of Russian avant-garde art, after the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg. When yet another artist fell out of Stalin’s favour, Nokis was conveniently far from Moscow, and Savitsky, the prescient museum director, was eager to house as much of their art as he could.

Due to its top-secret research facilities, Nukus was off-limits to foreigners during the Cold War. Such restrictions no longer apply, but the town still isn’t too high on the list of the discerning tourist – or any tourist, for that matter. Calum Macleod and Bradley Mayhew, authors of The Golden Road to Samarkand, one of the best introductions to Uzbekistan, describe Nukus as “a grim, spiritless city of bitter pleasures whose gridded avenues of socialism support a centreless town, only to peter out around fading fringes into an endless wasteland of cotton fields punctuated by the random, surreal exotica of wild camels loitering in neglected apartment blocks”. Even those trying to talk up the tourist potential of Karakalpakstan ruefully admit that the Tashkent Hotel in Nukus is “abysmal […] certainly a prime candidate for the worst hotel in the world”.

Nukus lies in the fertile delta historically known as Khwarezm, or Chorasmia. This is not to be confused with Khorezm (also written as Xorazm), which is the official name of an elongated, two-part (and non-autonomous) Uzbek province wedged between Nukus and Turkmenistan. This is but one example of the frustratingly complex borders designed just so for Central Asia (for the entire former Soviet Union, in fact) as an extra adhesive for the multi-ethnic communist state.

Further east, in the more densely populated Fergana valley, the potent mix of enclaves and exclaves, national majorities and minorities has caused enough trouble and bloodshed to either vindicate the peaceful superiority of socialist brotherhood of peoples, or, depending on your point of view, the perfidy of Stalin’s macchiavellistic reshaping of borders.

Even Karakalpakstan itself is the result of Stalin’s nationality policy. There never was a nation before it that bore its name. It existed as a plan before it was a reality. Its aim was to remould disparate communities of herders and fishermen into a coherent, cotton-growing subspecies of the Homo sovieticus.

But in true Soviet style, ethnic autonomy was a fraud in all but name: the Karakalpaks constitute no more than a third of population of the republic that was named after them. They are outnumbered by Uzbeks (36%), and further marginalised by large numbers of Kazakhs (25%). The remaining 6% is composed of Turkmen, Russians and other former Soviet nationalities.

Not to be confused with a much less numerous Turkic people in the Caucasus called the Karapapaks (which confusingly also means ‘Black Hats’), the Karakalpaks speak a language most closely related to Kazakh. Before it gained autonomy in the 1920s, a large part of their territory had been in what was then called the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (but which was in actual fact the precursor of present-day Kazakhstan, not Kyrgyzstan). In 1936, it was transferred to Uzbekistan.

Historical and linguistic ties prompt Kazakhstan to see itself as the ‘protector’ of the Karakalpaks; and some of them would clearly prefer their republic to rejoin Kazakhstan. In the 1990s, this caused considerable tension along the Kazakh-Uzbek border. A few armed cross-border incidents even caused a few casualties. Fortunately, this shocked both sides into attempting to deflate the crisis; the border was demarcated and demilitarised, leaving the Karakalpaks to their fate of peaceful, toxic obscurity.

Long after the Man is gone, decades after the Plan was retired, and while the Canal continues to sap the strength from its river, the only thing that remains is not the Panamanian palindrome, but a straight-A nation forgotten by history, and stuck under a toxic cloud.

This map of Karakalpakstan found here, on www.karakalpak.com.

Strange Maps #631

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.