Enigma, Georgia: Mystery of the South’s Circular Towns

So Cheney Lavonia has a job for me. In Thailand. Could I email her back? The message is spam and the name is fake, but the pseudonym is both mellifluous and intriguing. It seems haphazardly soldered together from a roster of vice presidents and an atlas of vanished kingdoms. Perhaps someone somewhere is getting this from Gore Burgundy or Agnew Aragon.

Lavonia, Lavonia… Wasn’t there a duchy of that name once in the Baltics? And are there any cool maps of it floating around the internet? At Strange Maps HQ, even unsolicited email can be an excuse for a good old maphunt – after all, spam is maps spelled backward.

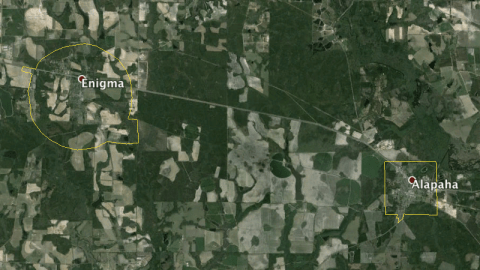

As it turns out, the Baltic region is called Livonia – it was mentioned in passing in #576. But that doesn’t mean Lavonia isn’t out there. That name too has a solid toponymical ring to it. If it doesn’t exist, it should. And… it does. The Google search returns a hit: a small town in the US state of Georgia. The results page includes a map of the town. And this is where things get weird. Something funny is going on with Lavonia’s municipal borders.

On the map, Lavonia looks like a manta ray. Or a space ship. The tail of territory bending in sync with State Route 17 somehow suggests movement, and various flappy bits could be fins, or turrets. But the remarkable thing is the body of the burg to which all these parts have been attached. It is eyecatchingly clear that Lavonia’s original town plan, before all those bits and bobs were added, was a perfect circle.

Circular borders are rare – boundaries tend to shadow natural features, reflect historical divisions or follow straight lines. Almost all US state lines, for example, are either squiggly or straight. Only one follows an arc: the so-called Twelve Mile Circle, marking the border between Delaware and Pennsylvania (discussed in #67). This border also shows the peculiar problems circular borders can cause – in this case: a disputed area called the Delaware Wedge, between the Circle and the next straight line (see #68).

But in Lavonia’s neck of the woods, round borders are anything but rare. Zoom out of the town and into other municipalities in the northeast corner of Georgia, and it looks like most have circular town plans, many even more pristine than Lavonia’s.

To the east, Hartwell also has sprouted addenda in all four directions, but is still recognisably circular in origin. Bowersville, to the south, has remained perfectly round but for a couple of dents at its northern edge, as if a neighbouring town took a bite out of it. Canon, just down the road, has lost and gained some ground, but for the rest is as round as a cannon ball. Carnesville and Royston are two other circular towns in the neighbourhood – and there are more.

Circular town plans are not limited to northern Georgia. The town of Plains, closer to Florida’s state capitol in Tallahassee than to Georgia’s in Atlanta, is perfectly circular but for a recent excrescence to the west, encompassing the Sumter Retirement Village and part of the National Historical Site dedicated to its most famous native son, Jimmy Carter, the 39th US President.

So there definitely is something rotund in the state of Georgia. Zipping over the state in Google Earth, with the City Boundaries option selected (in Layers, under More, then US Government), circular town and city borders are superabundant – if you include the ones that have been altered, but still are visibly round in origin, there are dozens of them, perhaps hundreds.

Take for instance the neighbouring towns of Leslie and De Soto, on State Route 30 west of I-75: two circles together looking like an old-time penny-farthing bicycle. Leslie is the bigger wheel, with a radius of exactly three quarters of a mile. De Soto is the smaller one, with a radius of half a mile.

Considering that the surface of a circle is pi (approximately 3.14) times the radius squared (A= πr2), that gives Leslie an area of almost 1.77 sq. mi. De Soto would cover an area of about 0.78 sq. mi, but it is less of a perfect circle than its bigger neighbour. It has a small extrusion on its western edge, that on Google Maps almost but not quite kisses Leslie. If you’re a border hunter, you could go stand on the 50 feet or so of Holley Street that separate the the two towns, and the hair on the back of your neck would probably stand up thanks to the static energy generated by the proximity of these two circularities. If that’s not a good enough reason to swing by, you could then drive into Leslie to visit the Georgia Rural Telephone Museum. Or you could just stay at home and think: Leslie De Soto – good spam name!

The town of Zebulon, south of Atlanta, is surrounded by a host of other souped-up circles, making the area look like a spaceship convention.

A comparable gathering on the edge of Athens shows a motley crew of modified disks, one being particularly puzzling: Winterville looks like the merger of two half circles: a larger one where it is surrounded by Athens (radius: three-quarter mile), a smaller one on the other side (radius: half a mile). How did this happen?

Leaving the next-level weirdness of Winterville to one side, both group portraits indicate that most circular towns come in either of two sizes: with a half-mile or a full-mile radius. As confirmed by this map of Eatonton and surroundings, between Athens and Macon, resembling an aerial view of the English county of Wiltshire at the height of the crop circle season.

Talking about crop circles: this view of Donalsonville and Iron City, near the Georgia-Alabama-Florida tripoint, not only neatly shows the contrast between the square and circular shapes of both towns, but also how Iron City’s roundness is much more in tune with the region’s circular agriculture.

There are plenty of Georgia towns that are perfectly round, as for example Oliver, near the Savannah River that forms the state’s border with South Carolina: as circular as its own initial.

But is roundness a lack of ambition? This map, a bit north of Oliver, shows the contrast between Hiltonia, small and still perfectly round, and Sylvania, bigger to start with, and by now sprouting several appendages that are the hallmark of municipal ambition.

Darien, at the mouth of the Altamaha, demonstrates how not all municipal circles are platforms for growth: it’s been reduced to a pitiful half-disk. This is somewhat reminiscent of Washington DC: another perfectly geometrical figure vandalised by a river.

As this map of places with circular limits (1960) shows, it’s safe to say that Georgia is the ground zero of the O-shaped town, but not the only place where circular municipalities occur. There are quite a few across the border in South Carolina.

Like this little cluster, halfway between Greenville and Columbia, showing the perfectly round towns of Cross Hill and Silverstreet, and the post-circular city of Newberry.

South Carolina even has a world-class example of circular weirdness in the twin towns of Livingston and Neeses: the former is perfectly – by now we can say: ordinarily – round, but it seems to leak that roundness south to envelop the latter. The southern border of Neeses indicates that it too must have been round once. Why did it cast the edges of its roundness upward, in perfect alignment of the edges of Livingston, turning that town’s circularity into a kind of bat signal projected onto the map?

A cursory flyover of other states seems to indicate that it is absent in many regions of the country (e.g. New England and out West) and very rare elsewhere – but not unknown. Like in Alabama, where the round town of Oakman lies near the town of Parrish, with its more conventionally boxy borders.

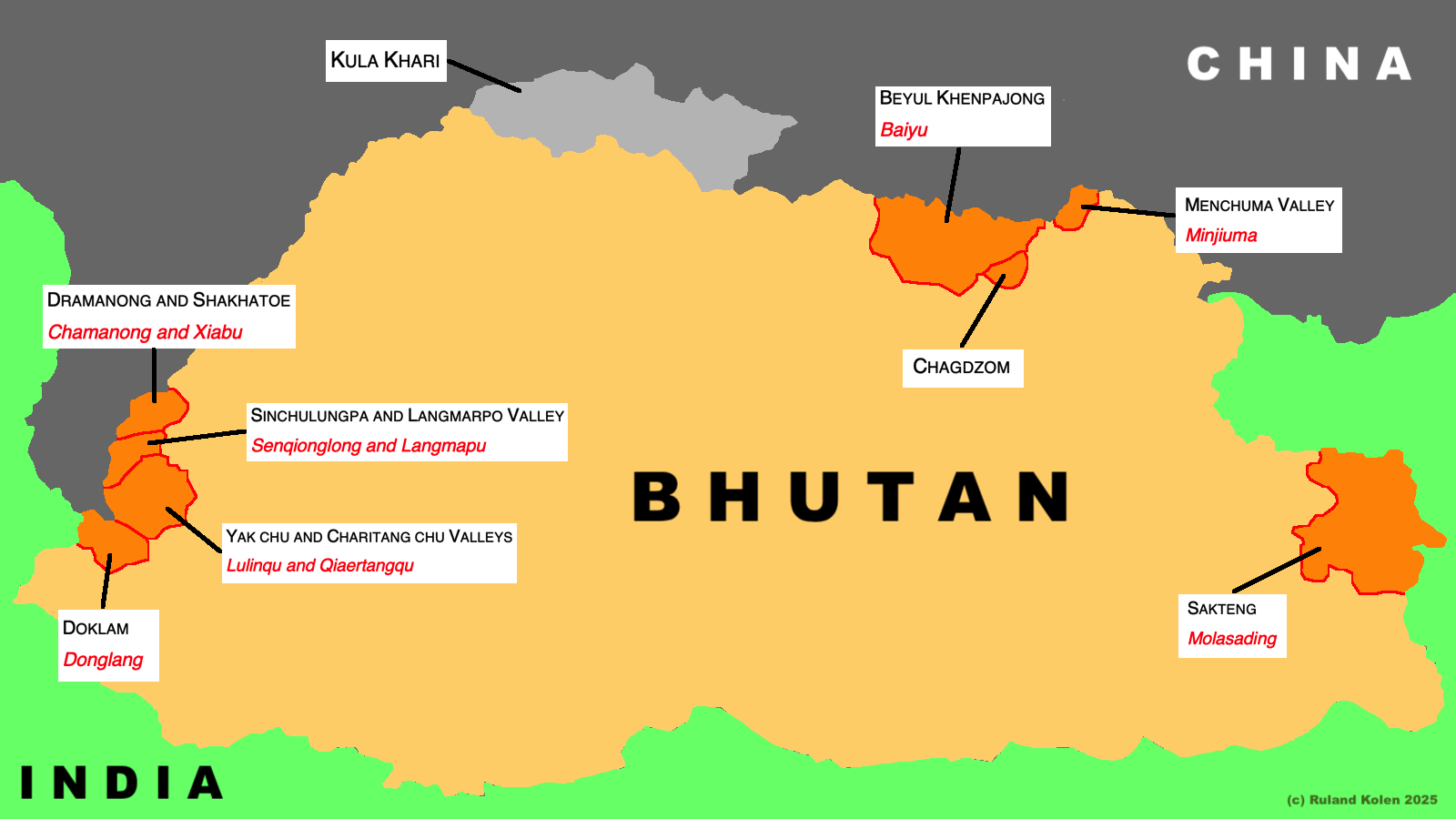

Rural Settlement Patterns in the United States, a National Academy of Sciences study from 1956, simply notes that “circular town boundaries [are] a feature quite typical of southeastern United States”, but does not elaborate or explain. So where does this curious Zone of Roundness come from? It’s a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an… Is it a coincidence that one of Georgia’s circular towns is called Enigma?

The Atlas of Georgia (1986) states that circles were used because of “[…] the advantages of explicit verbal clarity, directional impartiality, and ease of adoption”.

In layman’s terms: defining the town limits as a circle bigger than its centre means you have clear borders without actually having to demarcate them. But that still doesn’t answer two fundamental questions: If circular towns are so practical, why are they so rare? And if they are so rare, why are they so typical of town planning in Georgia and adjacent areas?

Without arriving at a definitive answer, here are a few attempts:

* Linearity has defeated circularity – again. The American victory of the grid system (from square city blocks to rectangular states) is a repeat of a similar struggle in Antiquity between round and square. Circular cities are hinted at by the astronomer Meton in Aristophanes’ play The Birds, In Plato’s Laws, the philosopher proposes a circular plan for the ideal city. Later, the Roman architect Vitruvius also prescribed the circle as the ideal shape for cities. For the circle symbolises perfection and the sacred. This would explain why Stonehenge and similar neolithic sites were round. But few if any ancient towns actually have circular city plans, and if so, seemingly more by accident than design. In the end, Roma Quadrata won out: the standard city plan exported by the Romans across the Empire was a square, divided in quarters by two main roads meeting in the centre. Roman centuriation (dividing larger territorial units into squares) was an inspiration for what would become the US Land Survey System.

* The idea of a circular layout for ideal cities would resurface in the Renaissance, when such cities were planned (Sforzinda) and even built (Palmanova). The chimera of the perfect circle as the perfect city would resonate all the way into the 20th century, with Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City movement (see also #234), but also with Mussolini and the construction of Littoria, the ‘ideal city’ of Italian fascism.

* An early indication of circular town planning in America dates from 1822, when the town limites of Madison, Georgia were extended to include “all land within one-half mile of the public square”, and to a full mile in 1849. The mid-19th century was the heyday of circular town plans. It lasted at least until the 1880s, when towns like Lavonia and Plains were incorporated.

* Could it be that this fashion for circularity, limited in time and place, was religious in origin? Nikolaus Zinzendorf, a leader of the Moravian Church in the mid-18th century, had proposed the construction in North Carolina of Unitas, a circular city, as “a perfect “marriage of mathematics and art”, but the plans were abandoned after his death. Unitas became Salem, North Carolina – a non-round town.

* Or did European colonists borrow the round shape of their towns from the land’s original inhabitants? Certain Native American towns in Virginia were round, and it is at least thinkable that this inspired the local custom of thinking in circles rather than squares.

However it may be (and your theories are more than welcome), not everybody holds the ideal of the circular city in high esteem. As William V. Spanos writes, in America’s Shadow: An Anatomy of Empire, he decries “ […] the military and disciplinary use to which the paradigm of the circular city was put after the Renaissance as the betrayal of the ideal envisaged by the humanists […] Inscribed by their humanist perspective on the circle, they fail to see, as Foucault does not, that this architectural model of beauty is also the model of domination”.

___________

Most images taken from Google Earth or Google Maps. Overview map of places with circular limits taken from this page. Map of circular Indian villages taken here from Project Gutenberg.

Strange Maps #655

Got a strange maps? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.