Mapmaker, not Moonraker: the Original James Bond and His Cartographic Legacy

Bond. James Bond. Not just a fictional character. Also a world-renowned ornithologist. With an unexpected cartographic legacy. The confusion between the two, and the overshadowing of the real person by the fictional character, begins in 1952, when Ian Fleming writes the first of his spy novels – to take his mind off his impending marriage.

Fleming wanted the protagonist of Casino Royale to be “an uninteresting man to whom interesting things happened”, so it was only fitting that his secret agent should have “the dullest name in the world”. The budding writer found the right name in the library of his home in Orcabessa, Jamaica. A keen bird-watcher, Fleming often thumbed through his copy of the standard field guide for the region’s feathered wildlife, Birds of the West Indies (1936). Written by… James Bond. That was to be 007’s name: “brief, unromantic and yet very masculine”.

Birds of the West Indies, by James Bond.

In the early 1960s, just as the first Bond movies were spreading the fame of her husband’s name-double across the entire globe, Mrs. Mary Fanning Wickham Bond (née Porcher) wrote a letter to Ian Fleming, in mock complaint of his unauthorised onomastic appropriation. The writer replied in an equally humorous vein, offering the ornithologist “unlimited use of the name Ian Fleming for any purpose he may see fit! Perhaps one day he will discover some particularly horrible species of bird which he would like to christen in an insulting fashion.”

James and Mary Bond, on a field trip to Maine in 1963.

No such instance is recorded. But, as the years passed and 007’s reputation grew, Mrs. Bond had more reason to complain: “Soft, female voices [would call] up at 2 or 3 in the morning, asking: Is James there? I finally put an end to such conversations by answering sharply: Yes, James is here, but this is Pussy Galore, and he’s busy now!” Mrs. Bond eventually arranged a meeting between her husband and Fleming, and the two became friendly, meeting up occasionally in the Caribbean. She eventually wrote a book about it, titled How 007 Got His Name (1966).

In fact, she too was a writer, producing magazine articles, novels, poetry, short stories and children’s stories. In 1980, she published To James Bond With Love, about her life with the ‘real’ James Bond, whom she married in 1954 and accompanied on his birding expeditions well into their sixties. She described her marriage as “a wonderful life […] He was a relaxed and charming person”.

James Bond (l.) meets Ian Fleming (r.)

Fleming’s dedication of a James Bond novel to… James Bond, presented at their first meeting, in February 1964.

James Bond was born in 1900 into a privileged Philadelphia family. After the death of his mother, he and his father moved to England, where he obtained his B.A. from Cambridge in 1922. He would retain more than a hint of an English accent for the rest of his life.

He was ushered into a career in banking, but resigned from the Foreign Exchange department at the old Pennsylvania Company to pursue his childhood obsession for natural history. In 1925, he accompanied Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee on an expedition to the Lower Amazon, looking for mammals and birds. The trip determined the rest of James Bond’s life. He decided to dedicate his career to the study of Antillean avifauna, because “probably more Antillean birds were in danger of extinction than in all the rest of the world”.

In 1934, he caused a furore in the scientific community by claiming that most Caribbean birds were North American in origin – except on Trinidad and Tobago and a few other islands. Until then, the consensus had been that the local bird species originally were mostly South American. Over the years, Bond supported his theory by field visits to over 100 islands, writing more than 100 papers.

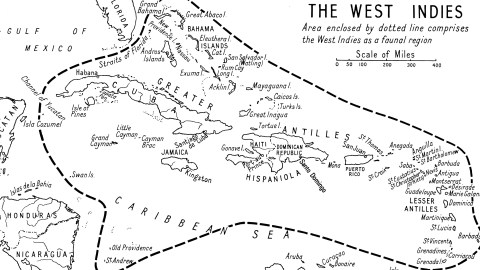

Bond’s theory has made a lasting impact on biogeography: in 1971, fellow ornithologist David Lack proposed naming the line that divided the Caribbean birds of North American origin from the others be called Bond’s Line: “Wallace has a line [see also #169] and after all your work in the West Indies, I don’t see why you should not have one too! I hope you will agree. As you drew attention to this line, it would be most fitting”. Bond agreed, and the line was first mentioned in Lack’s Island Biology (1976).

Bond’s Line, first proposed in 1971.

Bond’s Line includes most Caribbean islands and archipelagoes: the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, the Cayman Islands and Puerto Rico), the Lesser Antilles (from Anguilla down to Grenada), and a few isolated islands close to the Central American coast (Cozumel, Providencia, etc.) It does not include Trinidad and Tobago, the Islas Margaritas, and the Dutch islands of Aruba, Bonaire and Curacao.

Despite being overshadowed by his fictional namesake, James Bond achieved world fame in his field, and was awarded many academic accolades, among them the Leidy Medal of the Academy of Natural Sciences, as only the second scientist to receive it. James Bond died in 1989, Mrs. Bond passed away in 1997.

Many thanks to Mark Feldman for alerting me to the existence of the other James Bond, and his biogeographical legacy. Cover image for Birds of the West Indies taken here from Rolling Harbour Abaco. Picture of James and Mary Bond, of Fleming’s dedication and of the map image taken from James Bond Authenticus. Picture of James Bond and Ian Fleming taken here from the Audubon Magazine.

Strange Maps #672

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.