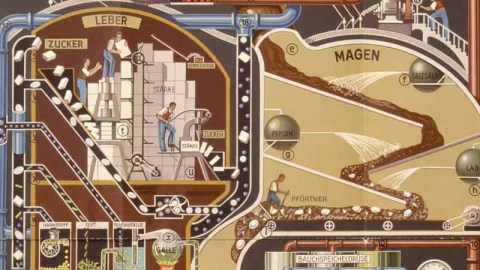

A Map of the Menschmaschine

Humanity is made in God’s image, and shares 96 percent of its DNA with chimpanzees. Does that mean that the Supreme Being is even hairier than most of us imagine Him? No. These are two incompatible points of view, the extremes in the tug-of-war over our species’ self-image: half angel, or wholly animal.

There is an interesting third option: men and women as “the most competent machines in the world.” That point of view was pretty popular just under a century ago in Central Europe. It gave us the word “robot,” the movie Metropolis, and this map.

Der Mensch als Industriepalast (“Man as an Industrial Palace”) was a free insert in Dr. Fritz Kahn’s best-selling series of books, entitled Das Leben des Menschen (“The Life of Man”). The five-part series, published between 1922 and 1932, was a success not just in Kahn’s native Germany — it was translated in many languages and published the world over. Check your attic for a mint-condition copy of the map: In 2013, Christie’s auction house in London sold one for £3,750 (app. $4,800).

Measuring 37½ x 19 in. (95 x 48 cm), the poster uses the industrial processes of the early 20th century as a metaphor for the workings of the human body. Kahn’s diagram in effect shows us the body as factory: The head is staffed with decision makers and switchboard operators, who dispense orders to the workers, who operate the heavy machinery in the body.

The two top offices are for Verstand, where a solitary figure is studying, and one for Vernunft, in which three operators are conferring on urgent and/or important matters. Both concepts can be translated superficially as “reason,” but Verstand connotes a more general, abstract common sense, whereas Vernunft implies a cleverness to solve practical problems. At least, that’s my understanding (Arthur Schopenhauer seems to disagree).

One floor down are the Drüsenzentrale (“Glandular control room”), where six dials and needles tell an operator whether the organs are up to snuff; the Muskelzentrale (“Muscular control room”), a switchboard for managing arms, legs and hands; and Wille (“Will”), another meeting room where three executives are trying to decide whether to go out for Bratwurst or stay in and heat up yesterday’s Eintopf.

Another floor down, an Atemzentrale (“Breathing control room”) keeps check on breathing, heartbeat, and coronary function; the operator of the Gehörorgan (“Ear”) is trying to make sense of the static coming in from outside; and the Auge (“Eye”) looks at the world through an old-fashioned folding camera. The Nervenzentrale (“Nerve center”), at the bottom of the head, relates all commands to the workforce via the Rückenmark (“Spinal cord”).

A fantastic array of shiny pipes and tubes, conveyor belts, and storage tanks make the lungs (Lunge), liver (Leber), stomach (Magen), kidneys (Niere), spleen (Milz), and other organs and glands look like the moving, clanking parts of a factory. Two main processes animate the workfloor: respiration, with the intake of oxygen (Sauerstoff) and the expulsion of carbonic acid (Kohlensäure); and nutrition, i.e., processing food (Nahrung) into ingredients that can be used to keep the factory humming and the lights burning.

In January 1927, around the time this map was drafted, Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis premiered at the UFA Palast, not far from Kahn’s Berlin gynecology practice. The parallels between map and movie are striking, and not just because both their creators are called Fritz. Both were influenced by Futurism, the early-20th-century artistic movement that celebrated technological progress. Both used the cogs and gears of contemporary industry as prominent elements of their creation. Those creations were both utopian — one corporeal, another social.

The capitalist society in Lang’s movie is also vertically structured, like a body: Those in charge are physically at the top, and the workers are down below. Only the middle is missing — and that is the central theme of the movie. One of the protagonists is the Maschinenmensch — one of the earliest cinematic depictions of a robot. That word, by the way, was first used just a few years earlier, in 1921, by Czech author Karel Čapek, for an anthropomorphic machine designed to work (robota is Czech for hard labour).

Kahn’s mechanical allegory of the human body, repeated throughout his various books in many other drawings, was in step with the spirit of the time. His works were very popular, but he slipped into obscurity, at least in his homeland, with the rise of Nazism.

Kahn was born in Halle in 1888 into an orthodox Jewish family. He studied medicine at Berlin’s Friedrich-Wilhelm University, specialising in microbiology. Kahn worked as a German army doctor in the First World War. Overworked and undernourished, he was invalided in 1918 while in Italy, and cared for by local farmers. After the war, he spent some time revalidating in Algeria.

Returning to Berlin, he worked as a surgeon and a gynecologist and in 1920 married Irma Glogau. Kahn was interested in a wide range of scientific and philosophical subjects, wrote articles for the popular science magazine Kosmos, and later expanded into a series of popular scientific books, mostly about medicine.

Kahn is credited with founding conceptual medical illustration. Earlier medical illustrations were purely realistic, and used mainly by medical students. Kahn wanted his work to be educational beyond purely academic circles. His work was aimed at popularising a scientific understanding of the workings of the body.

Kahn was one of the world’s first writers who aimed scientific knowledge specifically at as large an audience as was possible. He was a terrible draughtsman, though, so he instructed the artists in his atelier to design the drawings for him, to his very precise specifications. Those drawings did go on to inspire Walter Gropius, the architect and founder of the Bauhaus school.

As a committed Zionist, Kahn bought land on Mount Carmel and in Jerusalem in 1921 in what was then still Palestine. Back in Berlin, he founded a Jewish lodge. His travels, both for science and for his health, took him from the Polar Circle to the Sahara desert.

The rising tide of antisemitism forced Kahn from his job, and led to the burning of his works, which were placed on the list of “harmful and undesirable books.” One, Unser Geschlechtsleben (“Our Sex Lives”) was singled out for an active ban, with all available copies sought out for destruction. Some of Kahn’s drawings were “recycled” by Gerhard Venzmer, a medical writer favoured by the Nazis.

In 1933, Kahn emigrated to Palestine, where he got married for the second time, to Erna Schnabel, in 1937. They later returned to Europe, settling in Paris. When the Germans invaded France, he fled to Bordeaux. He was interned as an enemy alien by the French, but Erna secured his release and fled with him across the Pyrenees. In 1941, with help from Albert Einstein, they obtained a U.S. visa.

Kahn settled in Manhattan, but eventually moved back to Europe after the war, living mainly in Switzerland – with his Danish collaborator Ellen Fussing, after Erna had left him. In 1960, Kahn survived a major earthquake in Morocco — by sheltering in a sarcophagus. In 1962, he settled in Denmark, setting up an atelier in Copenhagen. He died in 1968 in Locarno.

Der Mensch als Industriepalast has become Kahn’s most influential work. In 1951, Barbara Jones selected the poster as part of her exhibition of popular art in the Whitechapel Gallery in London, inspiring Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi to some of his best-known works.

But, doubtlessly due to the burning of his books, and also to the diminished appeal of his post-1945 work, Kahn remained largely unknown in post-war Germany; until 2010, when the Berlin Medical Historical Museum, attached to the famous Charité hospital, mounted an exhibition entitled Menschmaschine, focusing on his work and that of the other Fritz. Der Mensch als Industriepalast had a central place in the show, and the poster would also figure prominently in subsequent exhibitions in the New Museum in New York (Ghosts in the Machine) and London’s Wellcome Collection (as part of Superhuman).

The wave of Futurism that propelled both Fritzes upward has long since crested and broken, but the human-controlled-by-tiny-humans trope survives in popular culture. One of the funniest examples is in Woody Allen’s Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask, when sexual arousal and performance is presented as an industrial effort by the ‘little men’ operating the human body. A more recent, but rather less funny example is the Eddy Murphy vehicle (in more ways than one) Meet Dave.

Dr. Kahn’s map of the Menschmaschine found here on Industriepalast, a website hosting the fantastic animation made by Henning M. Lederer based on the map.

Strange Maps #741

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.