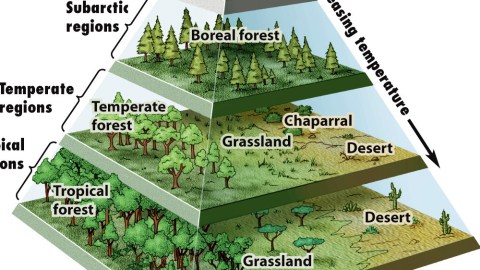

A Pyramid Map of the World’s Biomes

Pyramids don’t occur naturally (1). But this strange pyramid maps a lot of things that do. They’re called biomes, and they are arranged pyramidally to show where, why and how they occur.

A biome is a biological community of flora and fauna that has formed in response to a certain climate type. Add ‘em all up, and you have a biosphere – our biosphere. As indicated below and to the right of the pyramid, the two main determinants for each biome are temperature (hot/cold) and moisture (wet/dry).

The temperature factor has to do with a biome’s longitudinal location: hotter near the equator, colder near the poles (and also with its altitude: higher means colder). The moisture factor has the greatest impact on biome diversity near the equator, least near the poles – hence the diminishing area of each pyramid level towards the top.

This pyramid is an abstract rendition of either half of the globe: the same biomes can occur in both the northern and southern hemispheres. One could argue that a ‘southern’ pyramid would have to be inversed.

Tundra, at the top of this (northern-hemisphere) pyramid, derives from Russian (but ultimately Sami) and originally described zones in the extreme north of Russia where temperatures were too low and growing seasons too short for trees to grow. But the same treeless plains also occur in Kerguelen (see also #519), close to the South Pole.

The next level of the pyramid is occupied by boreal forests, also known as taiga (loaned by Russian from Yakut, where it means ‘impassable forest’). These vast forests of pines, spruces and other coniferous trees constitute the world’s largest biome (if we leave aside the oceans). They cover much of Scandinavia and Russia, Alaska and Canada.

There are also boreal forests in the Scottish Highlands, northern Mongolia and Hokkaido (see also #777). There is, however, no boreal forest in the southern hemisphere. Scientists speculate this is because there is not enough land mass in the southern hemisphere far enough from the sea for the climate to be cold enough for this type of biome.

Although all trees on this level of the pyramid are covered by the same definition (‘boreal forest’), the ones on the left look visibly taller than their stunted cousins on the right – a foreshadowing of the effect that the difference in moisture will have on the next level of vegetation. These are the temperate regions, and here we have no less than four different biomes. The temperate forests are well-watered, the grasslands less so, the high chaparral even less and the desert least of all.

The discrepancy is widest in the tropical regions: on the one hand, the lushness of tropical forests, on the other, the deadly environment of the tropical desert. In between, the grasslands, where life is hard and trees are rare. And to make matters even worse, there’s a giant pyramid hovering menacingly overhead.

Map, originally from a biology textbook by W.W. Norton & Co., found here at CookLowery16.

Strange Maps #859

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) One counter-example: the so-called Bosnian Pyramids. Although they came to prominence because a local amateur archaeologist claimed they were relics of a lost civilisation, it appears these intriguingly symmetrical hills near Sarajevo are natural in origin.