Ada Kaleh, an Ottoman Atlantis on the Danube

During the night of 22 to 23 February 2015, a Turkish Army task force went 25 miles deep into Syria to evacuate a tiny, Turkish-controlled plot of land on the left bank of the Euphrates. The focus of their attention was the safe removal of the Tomb of Suleyman Shah and the 40 Turkish soldiers guarding it. Anything else left behind was put beyond use with explosives.

Ankara felt its exclave was threatened by the approaching front line between Islamic State and the Kurds, whose offensive radiating from Kobane seemed poised to chase IS across the river. The Tomb has now temporarily been relocated to a place literally a stone’s throw south of the border: still inside Syria, but easier to keep an eye on. It’s not the first time the Tomb has moved and, along with it, Turkey’s territorial claim to the surrounding area. In 1973, the exclave shifted 50 miles north from its original location to avoid the rising waters of Lake Assad (see also #649).

Bizarrely, that exact fate had befallen Turkey’s only other exclave just two years earlier. Ada Kaleh, an Ottoman island in the Danube on the border between Serbia and Romania, disappeared beneath that river in 1971. In fact, one could be forgiven for thinking the Tomb of Suleyman Shah and the island of Ada Kaleh are cartography’s answer to the Lincoln and Kennedy assassinations — such is the number of weird parallels between both places.

- Both were located on great rivers.

- Turkey’s sovereignty over both exclaves was contested by their neighbors.

- Both were threatened by the construction of a dam downstream.

- Both consequently disappeared beneath the waves in the early 1970s.

- In both cases, removal of the exclave to another location on the river was proposed (unsuccessfully, in the case of Ada Kaleh).

- The remains of both exclaves were dynamited.

- Both places act as bookends to Ottoman history: the Tomb symbolizes its beginning, Ada Kaleh its end.

Turkey gave up the claim to its last Balkan possession in 1923, barely nine decades ago. Thus ended a centuries-old tug-of-war between east and west over an island, just 220 km downstream from Belgrade, the Ottomans once dubbed “the Key to Serbia, Hungary and Romania.”

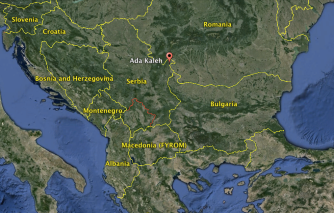

Although it’s been over four decades since Ada Kaleh has been wiped off the face of the Earth, there is at least one mapmaker that still upholds its memory — good old Google. Type in the island’s name in Google Maps or Google Earth, and you’re transported to a stretch of Danube just as blue as any other, except for the pin labelled… Ada Kaleh.

Zoom out a little, and you’ll find yourself in the Iron Gates, a stretch of the river winding its way through a spectacular set of gorges, about 40 straight miles north of the point where Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria meet. Set in the middle of Europe’s mightiest river and surrounded by these spectacular outcrops of rock, Ada Kaleh’s location was as exotic as it was strategic.

One mile long and a quarter mile wide, the island was a spit of sand and gravel thrown up by the Danube’s meandering flow. Some claim that the island was known to the ancients as Cyraunis, an island mentioned in the Histories (5th c. BC) as “covered in olive trees.” Although blessed with a Mediterranean microclimate — figs and almonds thrived on the island, but so did vipers and scorpions — it is more likely Herodotus was referring to the Kerkennah archipelago off the Tunisian coast.

Even more unconvincing (but nevertheless frequently repeated) is the claim that Ada Kaleh was the midpoint for Trajan’s Bridge, constructed in 101 AD to facilitate Rome’s troop movements during its war with the Dacians. The bridge was in fact constructed near Șimian, an island 20 miles downstream from Ada Kaleh, where its foundations are still visible. Destroyed in 230 AD, the Bridge held the record for world’s longest arch bridge for over a millennium.

One of the island’s first verifiable mentions is in an official report from 1430 by the Teutonic Knights, who refer to it by the name of Saan. Throughout history, it has carried many other names, including Caroline Island, Uj-Orsova Sziget (in Hungarian), Orsovostrvo (in Serbian) and Insula Orșovei (in Romanian), Neu-Orschowa (in German), Porizza (in Italian) and Aba-i-Kebir (in Arabic). Its most widely used name is Ada Kaleh, literally meaning “Island Fortress” in Turkish.

Far more charming, but completely unfounded, is the legend that says the island was named after a sultan called Kaleh, who was so in love with Ada, one of his wives, that he forsook the rest of his harem to live on the island with only her. She clearly felt less enthused at that prospect, drowning herself in the river.

Because of its location, the island became strategically significant during the struggle between the Austrian and Ottoman empires for dominance on the Balkan Peninsula. In 1689, Austrian troops built a pentagonal fortress on the island, which they called Neu-Orschowa. The fortress was destroyed by the Ottomans two years later (with a little help from their Hungarian vassals). Undeterred, the Austrians built another fortress after they regained the island in 1692. Perhaps they shouldn’t have: in 1699, the Ottomans took over the island for most of the next two centuries.

The Austrians did make two comebacks. In 1716, during the Second Austro-Turkish War, they took over again and, as if they couldn’t help themselves, again started reinforcing the fortress. It didn’t do them much good: after a four-month siege in 1738, during the Third Austro-Turkish War, they were kicked out again. The Austrians came back again briefly in 1789, during the Fourth Austro-Turkish War, but returned the island in the Treaty of Sistova (1791).

That treaty concluded the long series of Austro-Turkish conflicts that had started in 1526 with the Battle of Mohacs. In the 19th century, Ada Kaleh would gradually lose its strategic importance, even as Ottoman power in the Balkans waned. But the island remained a magnet for history-book events. In 1804, Serbian rebels led by Milenko Stojković caught and executed the Janissary junta who had fled Belgrade and taken refuge on the island. It was plundered by the Russian army during the Turkish-Russian war of 1806-1812. Lajos Kossuth, the leader of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, found refuge on the island after its collapse.

In 1867, the Ottomans evacuated Serbia. And following defeat in the Turkish-Russian war of 1877-78, the Sublime Porte was forced to grant independence to Romania, losing all its possessions north of the Danube. Following age-old tradition, the Austrians had taken advantage of the Ottoman retreat to re-occupy the island. But a funny thing happened during the Berlin Treaty of 1878 that formalized the new geopolitical reality: it simply forgot all about Ada Kaleh.

Soon, a strange accommodation took root: Austro-Hungary was the de facto overlord, but the island’s inhabitants remained de jure subjects of the Sultan, who retained the island as his personal possession. When in 1903 a mosque was built on the foundations of a former Franciscan monastery, the Sultan himself paid for its 30-by-50-feet carpet. Ada Kaleh also kept such trappings of Ottoman governance as a Mudir (mayor) and a Kadir (judge), appointed by Constantinople.

The Ottoman flag continued to fly over Ada Kaleh, but its citizens were exempt from tolls, taxes, and military service — Ottoman as well as Austro-Hungarian. But the islanders were able to vote in the momentous Ottoman general elections of 1908, the first since 1878, and the first to be contested by political parties.

The island’s peculiar place in the world inspired Mor Jokai, one of Hungary’s most famous 19th-century authors, to write Az Arany Ember (“The Golden Man”) in 1872. A thinly disguised Ada Kaleh is called “No Man’s Island” in the book, as it manages to obtain a charter from two rivaling empires, guaranteeing its existence “outside all borders.” Jokai paints the island as a utopian paradise beyond time and place, where peace and beauty rule supreme, far from war and nationalism.

But nationalism did strike Ada Kaleh. In 1913, Hungary — which at that time still extended to the northern shore of the Danube — unilaterally annexed the island. It would prove to be the country’s last enlargement before World War I, and as such, constitute Hungary’s territorial high-water mark. For after the war, the Treaty of Trianon (1920) would dismember it, and grant both the northern shore and the island itself to Romania.

Neither annexation was recognized by the Turks. As late as 1918, they insisted on sending a detachment of gendarmes from Constantinople to keep the peace on the island, its last European possession west of Edirne. The Turks finally gave up Ada Kaleh when they signed the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which established the Republic of Turkey as the successor to the Ottoman Empire.

In that same year, Ada Kaleh voted to join Romania — in the process losing its fiscal privileges. When Romania’s King Carol II visited the island in 1931, he was so struck by local poverty that he reinstated Ada Kaleh’s tax-exempt status. The island thus could resume its role as an exotic, romantic, and profitable destination, attracting tourists by the thousands.

With its lush microclimate, its mainly Turkish population and its narrow, crooked streets, the free port of Ada Kaleh was a slice of the Muslim Orient marooned deep in Christian Europe. The locals survived from fishing and growing tobacco, but thrived on the tourist trade and on smuggling.

The island, dominated by the picturesque ruins of the fort, was practically the only place in Romania where you could get unfiltered Turkish coffee, from copper kettles that were boiled in sand. The main drag, called Ezarzia, was packed with coffee houses and shops specializing in textiles and jewelry. They also offered perfumes, Turkish delight, fruit jams, and tobacco products, all from locally grown crops. At the height of the tourist season, the streets of this “Little Turkey” were crowded, the air heavy with the smell of tea, coffee and Ada Kaleh brand cigarettes.

Ada Kaleh was a multicultural place. Its 600 to 1,000 inhabitants included Romanians, Hungarians, and Germans, but the majority of Turks were in fact a mix of Arabs, Albanians, Turks, and Kurds. The island’s peculiar status attracted some peculiar people. The Hungarian “raw-foodist” Béla Bicsérdy, whose philosophy mixing Zoroastrianism with veganism was immensely popular in 1920s Transylvania, briefly set up a utopian colony on Ada Kaleh. When people started dying from the extreme fasting promoted by the lifestyle guru, his cult collapsed. Discredited, Bicsérdy died in 1951 in Billings, Montana.

After the Second World War, Ada Kaleh found itself on the border between two different types of communism. Fearing its citizens would flee across to the less repressive Yugoslav side of the river, Romania restricted access to the island. Visitors had to hand over their passports, and were forbidden to spend the night on Ada Kaleh. Locals could not cross to or from the island after 8 pm.

Gheorghe Gheorghiu Dej, Romania’s communist leader, had a small factory built on the island to compensate the loss of employment. But he also signed the island’s death warrant: Dej negotiated the agreement with Yugoslavia to build the Iron Gates Hydroelectric Dam, which would drown the island. Some structures, including parts of the mosque, the bazaar and the graveyard, were moved to Şimian, but plans to move the community in its entirety to that nearby island came to nothing.

In 1965, some islanders joined the Turkish minority in Romania’s Dobruja region. They took the Sultan’s carpet along with them to the mosque of Constanța, on Romania’s Black Sea coast. Although Turkey’s flag no longer flew over the island, it had not forgotten about its last Balkan colony. In 1967, then-Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel visited Ada Kaleh, inviting its inhabitants to move to Turkey, which most of them did.

By 1968, the island was depopulated. Before the island disappeared under the waves in 1971, the remaining buildings, including the island’s distinctive minaret, were dynamited so as not to obstruct future shipping. And there it rests now, 130 feet below the surface of the Danube: Ada Kaleh, an Ottoman Atlantis, surviving only in legend, destroyed in exchange for a few thousand megawatts of electricity.

Ada Kaleh receives a fitting epitaph in the closing pages of Between the Woods and the Water, as Patrick Leigh Fermor reminisces about the place he visited as a young man in 1934, on his walk from London to Constantinople: “The islanders of Ada Kaleh have been moved to another islet downstream (quod non – FJ) and their old home has vanished under the still surface as though it had never been. Let us hope that the power generated by the dam has spread well-being on either bank and lit up Rumanian and Yugoslav towns brighter than ever before because, in everything but economics, the damage is irreparable. Perhaps, with time and fading memories, people will forget the extent of their loss.”

Maps of Ada Kaleh from Google Maps, Google Earth, Wikimedia Commons, and here on the Hungarian-language blog Falanzster. Pictures of Ada Kaleh from Wikimedia Commons.

Strange Maps #703

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.